Sandra Lawrence

[caption id="AtCoramsFoundlingHospital_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE FOUNDLING MUSEUM

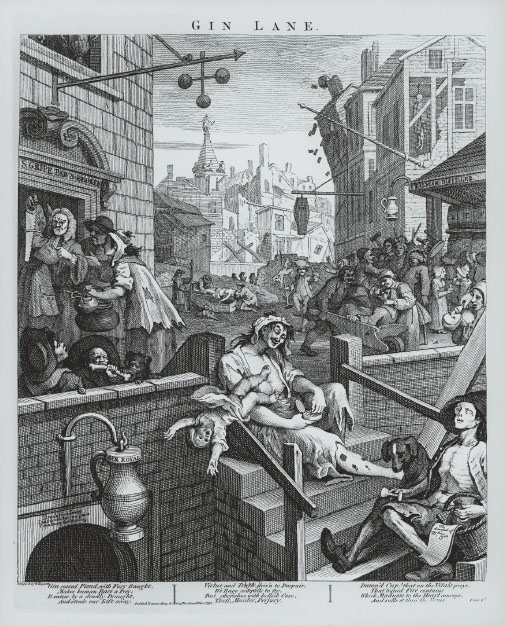

Thomas Coram was a sailor and shipwright who spent many years in America, first in Boston, then Taunton, Massachusetts. There was little love lost between Coram and the locals. His bluff, monarchist stance led to legal disputes with non-conformists, who considered this unapologetic Anglican the devil incarnate. For Coram’s part, he “hoped the inhabitants one day should be more civilised than they now are.” Despite successfully founding a shipyard (now Taunton Yacht Club), he did not return to England a wealthy man. Early 18th-century London horrified Coram. Children were expendable; 75 percent died before their fifth birthday. As he walked the streets, he was sickened at the “inhuman custom of exposing new born children to perish in the streets,” abandoned by destitute mothers for gin and prostitution. Coram had no money and no connections, but he was determined to do something to help. It took him 17 years. Coram’s notebook contains a list of influential people he was attempting to meet, along with the dates he finally managed to collar them. Aristocratic women were the secret to his success. The wives of nobility not only had the ear of their husbands and the Queen, they had little to do and, if it was fashionable enough, would throw themselves into a cause they supported. “Some of these women were very young,” said Harris. “They were very aware of their own vulnerability. A husband could take a mistress, but if a wife was even accused of adultery she could be thrown onto the streets.” Coram had to schmooze, no easy task for a notoriously tactless man, in what was to become the first “modern” charity fundraising effort. His no-nonsense approach often offended, but some found him refreshing after the insincerity of society life. Horace Walpole described him as “the straightest man I know.” Coram’s passion for the welfare of children was unquestioned. Even after he relinquished power in later years, he would continue to visit the foundlings, bringing gingerbread in his pockets.

Sandra Lawrence

[caption id="AtCoramsFoundlingHospital_img4" align="aligncenter" width="505"]

AKG-IMAGES-HOGARTH’S GIN LANE

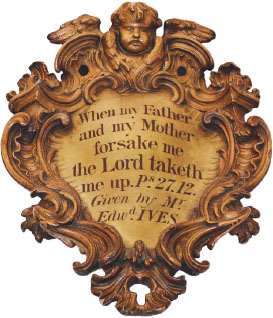

William Hogarth’s satirical paintings and engravings were the toast—and the scandal—of the town. They got him into trouble with authority, not least George II, but he saw eye to eye with plain talking Thomas Coram. Hogarth threw himself into the foundation, which became his exhibition hall and Britain’s first public art gallery. He even raffled one of his paintings for the cause. In what many have since dubbed an obvious fix, the hospital itself won. The painting still takes pride of place in the museum. Other supporters included Lord Byron, Sir Joshua Reynolds and four prominent doctors, including British Museum founder and chocolate-fancier Sir Hans Sloane, all of whom actually rolled up their sleeves to treat the orphans to the irritation of paying patients. Early adopters of vaccination, along with not allowing in any diseased children, they managed to keep the child mortality rate reasonable—the best you could hope for in 18th-century London. The Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children was incorporated in 1739, and a large hospital was built (in the old sense of the word, “a place of hospitality”) in what was then deep countryside. It’s Bloomsbury now, a short walk from Russell Square tube. At first, it mainly took babies of servant girls who had been seduced, often by their masters. Getting the child accepted wasn’t easy. “Fallen” women had to bring their babies to public lottery-style events, gawped at by the gentry, where each would take a ball from a bag. A white ball meant you were “in.” A black ball said you were “out.” A red ball allowed you on a reserve list in case any of the white-ball babies were rejected. The museum houses the original “billet-books.” Each child was left with a token—some small, cheap thing by which the mother might reclaim the baby if she ever came into money: a button, a thimble, an acorn. Distraught mothers would sometimes embroider little messages into their children’s clothes, beseeching their new carers to let them know where they could find them. The tokens were supposed to be given to the child on its majority. Mothers could apply to the hospital once a week and learn if their child was alive or dead. They, too, were being given a second chance—they may have fallen, but they now had an opportunity to redeem their lives. Of course it goes without saying that no mother was allowed to “fall” twice. In the 19th century, hospital secretary John Brownlow, an ex-foundling himself and possible inspiration for Mr. Brownlow in Oliver Twist was faced with a funding crisis fuelled by Victorian attitudes to “fallen women.” He wrote a history of the charity and, in a misguided but well-intentioned move, removed some of the tokens for display. Sadly now, this means those foundlings can never be traced by modern family historians, but the display remains as powerful as it is tragic.

[caption id="AtCoramsFoundlingHospital_img5" align="aligncenter" width="371"]

Sandra Lawrence

Children were separated from foster-mothers aged five without even saying goodbye, to live in the hospital run in military style by ex-military staff, because discipline was deemed best for them. An outspoken advocate for girls’ education, Coram insisted all children be schooled. Most sang; some learned instruments. Foundling boys often later entered the military as bandsmen. The hospital moved to Berkhamsted in the new “deep countryside” in the early 20th century. The original stairs and boardroom were preserved, however, and are in the museum built in the 1930s. Look out for the temptingly wide bannisters, once fitted with spikes after a boy was killed sliding down them. The institution stayed open to the 1950s, and there are still many foundlings around whose experiences have been eagerly recorded.

THE FOUNDLING MUSEUM

DANA HUNTLEY

DANA HUNTLEY

CORAM’S FIELDS

When the Foundling Hospital left London in the 1920s the original building was sold to a developer and part-demolished. Local people fought a long campaign to save the land for use by children and today seven-acre Coram’s Fields is a unique playground for anyone under the age of 16. Incorporating a youth center, sports, a café and even a city farm the area is fully staffed to allow safe play. No adults are allowed without an accompanying child. www.coramsfields.org The Coram Charity www.coram.org.uk The Foundling Museum www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk Carol Harris gives free guided walks on a regular basis. Details on the Foundling Museum website.

Comments