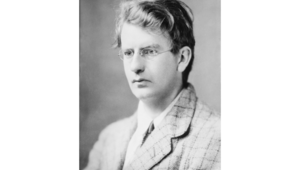

A portrait of George Thomason by Henry Raeburn.CC

George Thomson, whom history remembers best as the organizer and director of the first Edinburgh Music Festival, also deserves credit as a collector of Britain's national folk songs.

Without George Thomson's efforts, and those of other collectors who followed him, many of these traditional musical treasures would have been long lost to the ages.

Born in 1757, Thomson was the son of a schoolmaster at Limekilns, Fifeshire. When he was 16, George and his family moved to Edinburgh. There he found work as the junior clerk to the Board of Trustees for the Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures in Scotland. When the chief clerk died, George, in his early 20s, succeeded to the post, a job he held for 59 years. This public office provided sufficient income to allow him to pursue a hobby.

Thomson enjoyed singing and playing the violin, and he decided to publish an eclectic collection of characteristically Scottish tunes, together with the traditional lyrics. Unfortunately, the tunes Thomson found in existing collections were not always correct or melodious, and these flawed presentations disenchanted him. To suit them for concert use and to appeal to persons 'of taste', he decided to furnish the old tunes with new instrumental accompaniments.

Read more

Believing that no one in Edinburgh or London had sufficient talent to write the music, Thomson applied to several foreign composers. In 1799 he sent some Scottish melodies to Franz Joseph Haydn in Vienna, offering the eminent composer two ducats for each air. In June of 1800, Haydn forwarded to Edinburgh more than 30 airs he had arranged. Altogether Haydn worked on some 200 airs, including 'The Blue Bells of Scotland.'

Haydn, however, was up in years, so Thomson applied to Ludwig van Beethoven, a much younger man. In 1810 Beethoven sent to Edinburgh a number of Scottish airs he had composed 'con amore' by way of doing homage to the national songs of Scotland and England. But Thomson and the composer constantly argued over money. In Beethoven's last letter, dated 25th May 1819, he exploded over the pay he had received for his work.

Thomson felt that a number of charming old songs suffered from lyrics that were 'mere nonsense and doggerel' while others had rhymes 'too loose and indelicate' to be sung in decent company.

In 1792 Thomson applied to Robert Burns, the greatest of Scottish poets, to provide new words for 25 melodies that he, Thomson, would select. Burns agreed, provided his muse not be hurried. He also asked to include at least a sprinkling of Scottish dialect, but Thomson insisted that he avoid the vernacular as much as possible, since English was becoming increasingly the language of Scotland and young people were being taught to consider the Scots dialect vulgar. Burns contributed about 100 songs, both original and revised, before his death in 1796. These included 'Scots, Wha Hae,' 'John Anderson, My Jo,' and 'Highland Mary'.

In addition to Burns, who suggested expanding the collection to include Welsh and Irish airs, Thomson sought the help of various English writers. He wished to provide a number of Gaelic airs with alternative English lyrics that Southrons would understand. He rounded up a number of both Scottish and English writers to assist him, including Byron, Thomas Campbell, Walter Scott, James Hogg, John Gibson Lockhart, Joanna Bailllie, and Mrs. Anne Grant of Laggan.

If the songs failed in their intentions, the writers were not always to blame. Thomson delighted in presenting local colour, and if he could introduce Snowdon or Llangollen into a song, it might at once pass for Welsh. In her 'Maid of Llanwellyn', Miss Baillie's lyric spoke of the beautiful lakes in Wales. When Thomson objected, saying that Wales had no lakes, Miss Baillie haughtily answered that since lakes would not rise out of the earth for their convenience, and since she was unwilling to alter the line, they would just have to hope that their readers would be as ignorant as she had been when she wrote it.

Thomson edited three separate editions of national songs--Scottish, Welsh, and Irish. The Scottish songs were published in six volumes under the general title of A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice, with Introductory and Concluding Symphonies for the Pianoforte, Violin, and Violincello.

Thomson died in 1851, leaving two sons and six daughters. One daughter, Georgina, married George Hogarth, the Edinburgh music critic, historian, and Writer to the Signet. In 1836 the Hogarths' daughter Catherine married Charles Dickens. So Dickens' ten offspring were the great-grandchildren of George Thomson, the 'clean brushed old gentleman whose collections of traditional national songs are still sung around the world.

* Originally published in the Dec 1996 issues of British Heritage Travel magazine.

Comments