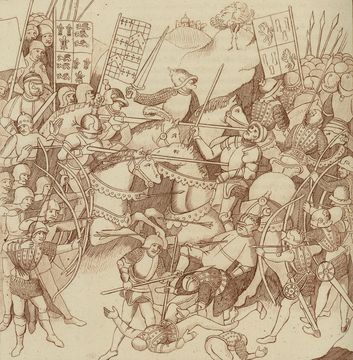

The Battle of Shrewsbury.National Library of Wales.

The Battle of Shrewsbury set the stage for the War of the Roses and ended Sir Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy’s quest for England’s crown…and his life.

Did the sun rise bloodily above the hill, and did the hollow whistle of the southern wind foretell the Battle of Shrewsbury on 21st July 1403, as Shakespeare ominously wrote in Henry IV Part I?

Dramatic portents of the Shropshire weather impressed 15th-century choniclers less than did the two armies that met on the field. Lancastrian King Henry IV’s ferocious army opposed rebel forces led by Sir Henry “Hostpur” Percy, the Earl of Worcester, and the Earl of Douglas.

Archers fired so vigorously that the sky turned black, they reported, and the missiles cut down the royal vanguard “like apples fallen in the autumn.” By the end of the day, Percy, “the flower and glory of Christian knighthood,” lay dead amid thousands of men. The crown and fate of England remained in King Henry IV’s exhausted hands.

Read more

The Battle of Shrewsbury (pronounced “Shrowzbury”) may not be as well known as some, yet it foreshadowed battles and strife to come. Shrewsbury was the seedbed that helped inspire Henry V’s spectacular victory at Agincourt in 1415, but also a wound that festered until the Wars of the Roses from 145 5 rained their brutal blood on English soil.

This year Shropshire’s county town on the England-Wales border commemorates the 600th anniversary of its momentous chapter in late medieval history. Music, drama, and re-enactments explore the episode from different, very personal angles, not least the artistic Licence of Shakespeare’s “Shrewsbury play.” Aptly enough, events are gathered under the banner “A Bloody Field by Shrewsbury,” the title of a novel about the encounter by local author Edith Pargeter (known as Ellis Peters to Brother Cadfael fans).

I drove two miles north of the town to the battle site to discover what happened on that hot summer’s day in 1403. Arriving in the late afternoon, the very hour when arrows first tore the air, I found St. Mary Magdalene Church holding dignified vigil in the open countryside. Built as a memorial chapel three years after the rebels’ defeat and with the permission of a grateful Henry IV, it stands on the mass grave of those whose bodies were never claimed. St. Mary Magdalene is the only church in Britain still on the site of the battle it commemorates. Not even Victorian restoration to the interior dilutes the haunting air of this beautiful, sad edifice. Anniversary services each July have a poignance undiminished by the centuries.

KING HENRY IV: How bloodily the sun begins to peer Above yon husky hill! the day looks pale At his distemperature.

PRINCE HENRY: The southern wind Doth play the trumpet to his purposes, And by his hollow whistling in the leaves Foretells a tempest and a blustering day.

—HENRY IV PART I

[Act 5, Scene I]

THIS YEAR A NEW, permanent viewing mound and interpretation panels have been erected around the battle site, and you can follow two (wheelchair-friendly) circular walks of two to four miles that bring to life the historic landscape. Hedgerows and pasture notwithstanding, it appears much as Hotspur saw it.

The Battle of Shrewsbury was the culmination of a dispute between Henry IV and the powerful Percy family of Northumbria. Just four years earlier the 2t Percys had helped Henry seize the throne from Richard II, but they felt the new King hadn’t fully delivered on due rewards and favour. For his part, Henry distrusted the Percys, who were related by marriage to young Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, and sympathetic to Mortimer’s claim to the throne via an alleged promise by Richard II. Henry marched north to “resolve matters,” and Hotspur, encouraged by potential support from Welsh rebel Owain Glyndwr, rode to meet him.

The two forces reached Shrewsbury on 19th or 20th July, but the King’s son, Prince Hal (later Henry V), had already occupied the town. Hotspur encamped a few miles to the north, and the King stationed himself nearby at Haughmond Hill. Negotiations to settle affairs peaceably soon broke down, with some chroniclers blaming the Earl of Worcester for misrepresenting to Hotspur royal messages of leniency.

Negotiations ended two hours before sunset, and combat commenced with fury. Each army numbered at least 10,000. Although Glyndwr never appeared, Hotspur, so-named due to his impetuous and daring exploits in battle, had the greater experience on his side. “He had one of the best military minds of his generation, having fought across Europe,” Mike Stokes, Keeper of Archaeology at Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, explained as we walked the battle site. “He had even trained Prince Hal.” Contrary to the impression given by Shakespeare, the two warriors weren’t of the same generation; Hotspur was nearly 40, Prince Hal just 15.

At first the Percy archers gained the upper hand, but Prince Hal’s men made a lightning charge from a hidden position to turn the battle. An arrow fired by an unidentified archer killed Hotspur, and the rout began. In three blistering hours, up to 9,000 men died or suffered mortal wounds.

“IT WAS THE FIRST MAJOR ENCOUNTER between Englishmen using longbows,” Mike continued. “With their long-range they were more effective than any weapon known at the time. Several thousand archers on either side could each fire 12 arrows a minute. Prince Hal later took the experience with him to Agincourt, where the initial English longbow volleys eliminated about 70 percent of the French nobility” despite the French force’s vastly superior numbers.

“The Battle of Shrewsbury was also important because it confirmed a dynasty, the House of Lancaster, on the throne. The emotional and political conflicts between the Houses of York and Lancaster, fighting on opposite sides for the first time, fossilized and were never solved until after the Wars of the Roses. Shrewsbury was effectively the end of the first chapter of the Wars of the Roses.” (Genealogists may also note that the Mortimers’ royal claims reaped some success, as Edmund’s sister Anne was the grandmother of Edward IV, the first Yorkist King.)

Following the 1403 battle, Prince Hal received treatment at Shrewsbury Abbey for an arrow lodged in his face. The victors impaled Hotspur’s body on a spear held upright between two millstones at High Cross in the centre of town, thus proving to his followers that he was dead. For the moment at least, the King had quashed the Percy rebellion.

OPEN-AIR PERFORMANCES of Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part I, close to the battle scene at Haughmond Abbey (16th-21st June), highlight the 600th anniversary. So too does the thought-provoking exhibition “The Arts of War and the Arts of Peace” at Shrewsbury’s Museum and Art Gallery in Rowley’s House (9th August-11th October), which explores approaches to peace and conflict in both the 15th and 21st centuries.

Few relics of 1403 remain, though a skull at the museum possibly belongs to a warrior from the battle. But I did find here a fine overview of the town’s “other” history. In Saxon times, Shrewsbury was known as Scrobbesbyrig, “the fort in the place of Scrob,” the local estate owner. The town was built on three hills within the horseshoe loop of the River Severn and is an island except for a 300-yard spit of land to the north-east. The Normans quickly utilized this ideal natural stronghold of the Welsh Marches, as did Edward I during his subjugation of North Wales. Charles I made it his capital-in-exile in 1642.

Shrewsbury’s border location also brought prosperity through business and markets. It grew wealthy through the Welsh woollen and flax trade in the 15th and 16th centuries. Having learned the lessons of 1403, the borough judiciously forbade the display of livery of the houses of York and Lancaster during the Wars of the Roses so as not to upset commercial stability.

The town’s famously charming half-timbered buildings date from this era of booming commerce. Shrewsbury boasts more than 660 listed historic edifices, exceeding any other town in England.

Everything in Shrewsbury is easily reached on foot. To get a whiff of military power I made my way to the red sandstone castle dominating the landward approach to the town. Originally the power base of Roger de Mungumeri, one of William the Conqueror’s most trusted deputies, it was later transformed into a private mansion. Today the Great Hall houses the Shropshire Regimental Museum that documents, among other things, local involvement in the American War of Independence.

SHREWSBURY

Roger de Mungumeri also built the Benedictine abbey on the south-eastern outskirts of town in the 1080s. This became a major destination on the pilgrimage trail just as soon as the wily monks had negotiated the acquisition of that medieval tourism must-have, a saint’s relics. In this case, they acquired St. Winefride’s bones from north Wales a tale explored in Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael mystery A Morbid Taste for Bones.

Shrewsbury’s streetscapes everywhere wind and turn with quirky interest and colourfully named “shuts” (shortcut alleys) like Grope Lane. I joined a walking tour from the Tourist Information Centre on The Square and found that most of today’s street pattern was already laid out by the end of the 11th century. We walked in the steps of Sir Philip Sidney to the former Shrewsbury School, now the Library, then followed Shrewsbury native Charles Darwin to medieval St. Mary the Virgin Church, renowned for its luminous collection of stained glass spanning six centuries.

“After Darwin’s death when the spire fell into the nave, the vicar blamed the congregation,” guide Pam Roberts-Powis revealed, “because they had been raising funds for a statue to him.” The monument stands outside the Library, and Darwin’s “sinful” theories on evolution didn’t stop the world from turning after all.

I finished my three-day visit with a delve into the Shropshire Records and Research Centre at Castle Gates. Archivist Sarah Davis showed me around the five and a half miles of shelving containing everything from a grant of land witnessed by Thomas Becket to parish registers. It’s a fantastic resource for family and historical research, and the centre’s documents are being used to create a permanent database for a Who’s Who in 15th-century Shrewsbury as part of the 1403 commemorations. Now that would have been useful to Shakespeare!

JOURNEY NOTES

FOR INFORMATION about visiting and accommodation in Shrewsbury, contact Shrewsbury Tourism, Development Services, The Music Hall, The Square, Shrewsbury, Shropshire SYI ILH. Tel: 01743 281200; fax: 01743 281213; email: [email protected]; website: www.shrewsburytourism.co.uk.

Other useful sites: www.shrewsbury.gov.uk and www.shrews bury.co.uk.

ACCOMMODATION Stay near the battle site in the Albright Hussey Hotel and Restaurant, the moated manor once owned by the Hussey dynasty who fought on Henry IV’s side and gave the land on which Battlefield Church was built. It’s on Ellesmere Road. Tel: 01934 290523; fax: 01934 291143; website: www.albrighthussey.co.uk.

The Prince Rupert Hotel stands on Butcher Row at the town’s medieval and Tudor heart and was once the private residence of the dashing English civil war commander. Tel: 01743 499955; fax: 01743 357306; website: www.prince-rupert-hotel.co.uk.

PLACES TO VISIT Town: St. Mary the Virgin Church, St. Mary’s Street. Tel: 01743 357006. Open: Monday-Friday 10 am-5 pm, Saturday 10 am-4 pm, Sunday by arrangement. Free, donations welcomed.

Shrewsbury Abbey, Abbey Foregate. Tel: 01743 232723; fax: 01743 240 172; website: www.shrewsburyabbey.com. Open: 31st March-26th October, 9.30 am-5.30 pm; 27th October-29th March 2004, 10.30 am-3.30 pm. Free, donations gratefully received.

Shrewsbury Castle and The Shropshire Regimental Museum, Castle Street. Tel: 01743 358516; fax: 01743 358411; website: www.shrewsburymuseums.com. Open: 25th May-28th September, Tuesday-Saturday 10 am-5 pm, Sunday and Monday I 0 am-4 pm. Winter 2003/04, please call for details. Adult admission charge for museum, grounds free. Museum is wheelchair-friendly.

Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, Barker Street. Tel: 01743 361196; fax: 01743 358411; websites: www.shrewsburymuseums.com, www.darwincountry.org. Open: 25th May-28th September, Tuesday-Saturday 10 am-5 pm, Sunday and Monday 10 am-4 pm; 29th September-May, Tuesday-Saturday 10 am-4 pm (closed Christmas-New Year fortnight).

Shropshire Records & Research Centre, Casde Gates, Shrewsbury SYI 2AQ. Tel: 01743 255350; fax: 01743 255355; email: [email protected]; website: www.shropshire-cc.gov.uklresearch.nsf.

Guided Tours of Shrewsbury depart from the Tourist Information Centre, The Square. Tel: 01743 281200. Depart 2.30 pm: May-September daily, October Monday-Saturday, November-April Saturday only plus Easter Sunday and Bank Holidays. Adult £3, child £1.50. Walks conclude at the castle and tea with the mayor on most Wednesdays May through October, subject to the mayor’s duties.

Out of Town: Battlefield Church St. Mary Magdalene, off the A49, 2½ miles north of Shrewsbury. Open 2 pm-5 pm summer Sundays. Key available from Battlefield Planthire, 65 Battlefield Road at other times. Check ww.visitchurches.org.uk for updated summer opening times. Free, donations welcomed.

A BLOODY FIELD BY SHREWSBURY COMMEMORATIONS A leaflet containing a full calendar of events commemorating the Battle of Shrewsbury is available from Shrewsbury Tourism, or visit www.battleofshrewsbury.org

A booklet, “The Battle of Shrewsbury 1403,” by E.J. Priestley, is available for £1 (plus postage) from The Tourist Information Centre and Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery.

SELECTED HIGHLIGHTS Themed Guided Walks: weeks of 4th, 11th, and 18th August, Tuesday and Thursday evenings at Battlefield Heritage Park. Three walks on the themes Landscape and Natural Environment, Historical and Archaeological Features, and The Battlefield and Contemporary Accounts.

(Take bus no. 14 from the town to the battlefield.)

The Battle of Shrewsbury Lecture Series includes “The Great War Bow”(11th July)and ‘Wounding at the Battle of Shrewsbury” (18th July).

DRAMA A Bloody Field by Shrewsbury, a dramatization of the novel by Edith Pargeter, goes on tour around the county (September); William Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part I at Haughmond Abbey (8 pm nightly 16th-21st June).

LIVING HISTORY AND ACTIVITIES Medieval Shrewsbury Open Day, concluding the research project “Who’s Who in Medieval Shrewsbury,” at Shropshire Records & Research Centre (10 am-4 pm 17th August).

MUSIC Slaughter and Salvation, medieval music at Battlefield Church (7.30 pm 21st June).

EXHIBITION “The Arts of War and the Arts of Peace” looks at approaches to peace and conflict in the 15th and 21st centuries, Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, Rowley’s House (9th August-lith October).

* Originally published in Jul 2016.

Comments