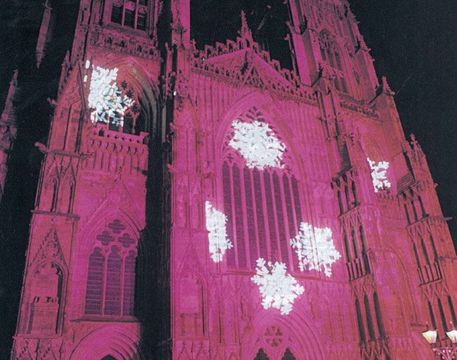

The facade of York Minster provides a medieval backdrop for a high-tech Christmas light show.

In this ancient capital of the north, medieval holiday traditions live on, often blending happily with a dose of something new.

Editor's note: Of course, due to the COVID pandemic travel is restricted somewhat and most events are canceled in order to obey social distancing. Let's just enjoy this article from a 2003 edition of British Heritage Travel and plan our Christmas outtings for 2021.

“Ten, nine, eight, seven..." It was dark and chill on a late-November night in York’s Duncombe Place, but an hour of laughing at skits from the actors in the Christmas pantomime had fuelled enough good spirits to keep the thousands gathered there warm and merrily counting. “Four, three, two, ONE!” they roared, as a local radio personality revved them up to the magic moment. Then, as if at the wave of a fairy godmother’s wand, the great west towers of York Minster were suddenly bathed in purple light.

It was the first time ever that the 13th-century Minster had been lit in colour, and the crowd loved it, especially when the purple became red, then green, then gold, and six huge projected snowflakes floated by, picking out details of carving and sculpture usually obscured by distance. It was, as they say in the North of England, “a good do”: one of Europe’s greatest medieval buildings brought gloriously alive by 21st-century lighting technology.

Read more

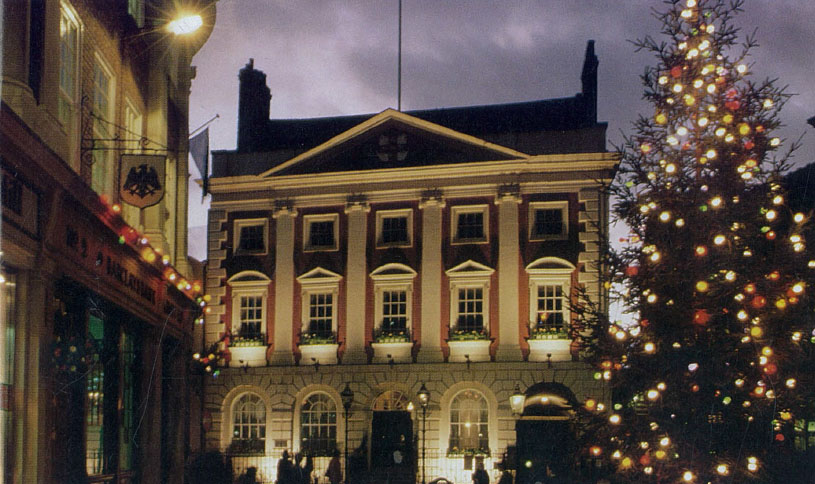

This tapestry of the ancient and modern typifies York—and indeed the rest of Britain—at Christmas. Officially, the lighting ceremony initiated York’s St. Nicholas Fayre and the Christmas shopping season. Unofficially, though, York, like other British towns, had been readying itself for weeks.

Christmas planning begins early in Britain. As summer’s vacationers disappear, hotels, pubs, and restaurants advertise their holiday menus, encouraging customers to make reservations for office parties and other festive get-togethers. Stores of every ilk suggest that their stock in trade makes just-the-most-perfect Christmas gifts. High Street clothing shops bedeck their windows with glittery party wear. Supermarkets display lavish boxes of chocolates and tins of biscuits. And almost everywhere, you can buy boxes of Christmas crackers to snap. Inside hides a paper hat—and wearing it is de rigueur—a joke or riddle to be read aloud, and a trinket or toy to keep as a souvenir of the day.

On a wintry morning, a signpost outside York Minster points out the way to the historic city’s many attractions. Nighttime at the St. Nicholas Fayre. Enticing holiday fare is a centrepiece of many York Christmas celebrations. A taste of history. BAILEY COOPER.CO.UK

WITH SO MANY ALLURING THINGS TO BUY, perhaps nothing tempts more compellingly than the food stores, especially bakeries and confectioners. York’s favourite is Betty’s on St. Helen’s Square. As Christmas nears, tired shoppers gather inside for lunch or afternoon tea. Passers-by, drawn to the window by alluring arrays of mince pies and Christmas cakes, crowd the pavements outside. Traditionally, Christmas cakes come robed in layers of marzipan and immaculate icing topped with Christmas ornaments. But Betty’s offers many variations round cakes and square cakes, cakes topped with fruit and nuts for those who don’t like marzipan, or covered with marzipan but not icing for those who don’t like sugar, or left plain for those who want to decorate their own. The mince pies vary from the traditional covered tartlets dusted with confectioners’ sugar to pies with star-shaped lids or fillings that combine cranberries or blueberries or almonds with the traditional mincemeat.

The food at the outdoor Yorkshire Pantry Market in St. Sampson’s Square also harmonizes old and new themes’. Forty stalls offer confectionery, preserves, cheese, pies, sausages, meat, beer, and smoked foods from local producers. And almost every stall features an absolutely traditional treat along with a variation that makes it absolutely modern, too.

Take Wensleydale Cheese, for example. Historically, the cheese comes in two forms: white and blue. But now the Wensleydale dairy at Hawes makes Wensleydale apricots, pears, fruit, nuts, ginger, mustard, and an array of other flavourings. Among these, cranberry Wensleydale in packages illustrated with those famous Wensleydale fans, Wallace and Grommet, has already become a Christmas favourite on both sides of the Atlantic. Adventurous shoppers eagerly sample tastes of other cheeses with chocolate or beer or herbs as they look for something just a little different to grace their Christmas tables.

The same scene occurs at other stalls, too. Yorkshire Country Wines serves samples of fruit wines: gooseberry, elderberry, blackberry, damson, and cherry. Deer-farmer Richard I Elmhirst suggests his venison as a luxury alternative to turkey or beef for Christmas dinner. Mackenzies of Blubberhouses offers an array of smoked meat including wild boar—a reminder that Richard III, whose emblem was a boar, was a Yorkshireman. Botham’s of Whitby, founded by Elizabeth Botham in 1865 and still run by her descendants, brings Whitby Gingerbread. They are the last surviving bakers of this traditional speciality—a gingerbread loaf whose texture lies somewhere between a bread and a cookie—perfect with cheese, and just the thing for a Christmas gift.

They also offer a contemporary ginger treat, their luscious Ginger Brack studded with chunks of juicy Australian ginger. (Australia is perhaps dear to their hearts because its English discoverer, Captain James Cook, was born near Whitby in 1728, and Botham’s is helping fund the restoration of his ship, the Resolution, by selling a special blend of tea named—what else?—Resolution Tea.)

The Yorkshire pantry market is not the only Christmas market vying for customers in York. Throughout the holiday season, the ancient streets and medieval halls of York come alive with traders selling their wares. Parliament Street is home to Made in Yorkshire, a craft fair featuring ceramics, paintings, woodwork, textiles, and other artefacts made by the local artisans. In mid-December, farmers take over the street with their meat, cheese, and vegetables. Nearby, the year-round, seven-days-a-week Newgate Market has 120 stalls selling everything anyone might need for Christmas.

MANY OF YORK’S INDOOR MARKETS take advantage of the city’s most prized historical buildings. Medieval St. William’s College, located next to York Minster, hosts a Craft Fair, while the Merchant Adventurers’ Hall, a medieval guildhall virtually unchanged since its building in the 1360s, makes a perfect venue for the St. Nicholas Antique, Curio, and Collectors’ Fair. This is the place to find a piece of bone china to complete a set, some antique glasses for your holiday table, brass fire irons to gleam a welcome from your hearth, old prints of York, a piece of ancient lace, and much more, generally at very good prices.

Perhaps the most extraordinary of York’s medieval buildings in the mid-14th-century Barley Hall. Though it stands in the centre of the historic city, just off busy Stonegate, it went unrecognized for hundreds of years because it had been incorporated into a jumble of 18th- and 19th-century brick buildings. When a developer interested in erecting an office block asked for an archaeological survey in 1984, the surveyors discovered that the alleyway linking Stonegate to Coffee Yard was in fact an internal corridor of a medieval house. Year of patient detective and restoration work finally restored the building to what it must have looked like in 1361 when it was built for the Prior of St. Oswald’s Priory at Nostell, who needed a handsome townhouse when he came to do business with the Archbishopric.

With this record of bringing the past back to life, Barley Hall is a fitting place to house a craft market devoted to contemporary reproductions of medieval objects. Craftspeople, dressed in the gowns and headgear of an earlier era, demonstrate their skills while they sell their wares. One artist engraves his customers’ names in runic on bracelets and other metal objects.

Another paints jewel-bright miniatures onto note cards and bookmarks. A third makes deerhorn items, including combs modelled on Viking combs found in York. Others knit caps and mittens from Yorkshire wool dyed with the natural plant-based dyes used by earlier generations. A cobbler makes sandals. A calligrapher transcribes medieval and Renaissance texts onto fine paper. Potters fashion earthenware pitchers and plates. Glassblowers make travellers’ flasks with twisted necks designed to prevent spills. And as delighted buyers find unusual presents, a maker of ancient instruments fills the air with limpid notes that cascade from the lutes he fashions.

LIKE THE SHOP WINDOWS FULL OF GLITTER, these markets represent the busy commercial side of Christmas. But York does not forget the spiritual and aesthetic significance of the season. York Minster has religious celebrations beginning in November. York Early Music offers a series of Christmas concerts—some staged in the Minster itself, and others in the National Centre for Early Music in Walmgate. Many of York’s ancient churches and choral societies schedule annual carol services and concerts. One of the most beloved of these, especially for those who like to join in, is Carols in Kirkgate. This annual event, scheduled for four December evenings, brings the York Philharmonic Male Voice Choir and lots of York residents to Kirkgate, a pretty Victorian street that rings to the joyful sounds of Christmas music.

Every bit as popular as the carol services, but at the farcical end of the aesthetic scale, are the pantomimes, without which no English Christmas would be complete. Last year it was Babes in the Wood at the Theatre Royal and Aladdin at the Opera House. Pantomimes trace their ludicrous revelry back to the Middle Ages, when the twelve days of Christmas were given over to rambunctious feasting. Servants anointed king and queen for the day ruled over a topsy-turvy world in which lords and sobersides were the butt of their underlings’ jokes. In just this way, every pantomime has a Principal Boy who is always played by a woman, while the Pantomime Dame must be a man—usually a well-known radio or TV comic. The jokes come fast and furious, the plot often gets lost in the hilarity, and the audience, which always includes lots of children, plays its part with sing-alongs, applause, comments on the action, and for a chosen few, even visits to the stage.

MEDIEVAL YORK

The spirit of York’s medieval past lives on at Barley Hall, a 14th-century townhouse that now hosts a crafts fair. CHRISTOPHER CORMACK/CORBIS

The other visit that children everywhere love to make is the trip to see Santa Glaus—generally called Father Christmas in Britain. In York he can often be found wandering round the street markets, most significantly when he appears in Santa’s Grotto in St. Sampson’s Square.

Traditionally, of course, he travels by sleigh, but if that seems outdated, York’s children can also visit him on a boat that cruises down the Ouse. Or they can go to the National Railway Museum and catch him on a train. Even more up-to-the-minute, they can take a short trip to the Yorkshire Air Museum in Elvington and see him aboard his own personal plane.

With its many museums, ancient streets, its towering Minster, and dozens of other lovely buildings from every era, York has everything to make a marvelous setting for Christmas, and local musicians, actors, artisans, farmers, and merchants give of their best to make it a splendid place to visit during the festive season. So, too, are other cities in Britain, all of which have their own special events. With Christmas parties starting in November, and a Christmas holiday that stretches from 23rd December and on over Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day (26th December), and then on into New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day, the contemporary British Christmas seems bang up-to-date in its festivities, but it’s all rooted in the merriment of the 12-day Christmases of old.

* Originally published in Dec 2003.

Comments