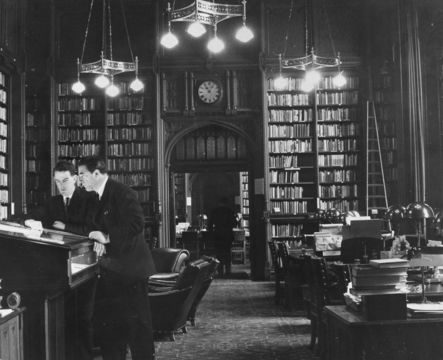

British Labour politician and newspaper proprietor Robert Maxwell (1923 - 1991) being shown around the House of Commons library by Tam Dayell before the opening of Parliament.Image: Chris Ware/Keystone Features/Getty Images

Throughout British history, we have seen many politicians and figureheads earn huge sums of money for their roles as politicians. Has it always been this way?

After the Battle of Blenheim in August 1704, the British commander and hero of the War of the Spanish Succession was made the Duke of Marlborough. Along with John Churchill’s title came a bauble called Blenheim Palace, in appreciation for his public service. After making mince of Napoleon, the Duke of Wellington got the street address Number One, London, and a fine house to go with it.

Read more: Inside Balmoral Castle - Queen Elizabeth II's holiday home

Come to that, most of the great landed estates and titles in Great Britain began as rewards for public service. The notion that service to Crown and Country brings rewards of good living, economic advantage and even wealth is deeply engrained in the British psyche.

For most of its 2,000-year history, that’s how the system worked. Particularly after the political demise of the Church in the 16th century, service to the monarch or the feudal establishment was the only real means of economic or social advancement.

'The idea that the public office ought to bring economic rewards has proven tough to slay'

Old notions die hard, and the idea that public office ought to bring economic rewards has proven a tough one to slay. The expense scandal that has rocked Parliament and dominated the public forum this summer comes from Britain’s own collective psyche.

What happened was this

Parliament’s rules allow MPs to be reimbursed for the cost of a second residence. Unlike in the States, MPs need not reside in, or have any necessary connection with, the constituency they represent. Their party candidates are chosen by local committees, not by direct election. Thus, a second home allowance lets MPs maintain residences both in the constituency they represent and in London.

The expenses of running that home, whichever one is designated the “second” home, including maintenance and furnishings are all reimbursed by the Fees Office.

The Fees Office, hidden in the Houses of Parliament itself, is answerable or accountable to no agency beyond Parliament itself, and its records have been carefully shielded from the public. After being pressured to release hither-to protected MP expense reports, the Parliamentary Fees Office found a leak that soon became a flood. The Daily Telegraph began publishing detailed reports on a torrent of MPs whose claimed expenses exceeded the bounds of reasonableness, decency, and legality.

Literally scores of MPs, from all three political parties, were caught in the embarrassment of having their expense claims brought to light. Abuses weren’t just occasional and mistaken, they were systemic and outrageous. The Home Secretary, Jacqui Smith, claimed back expenses for her husband’s adult movie rentals; several of Gordon Brown’s cabinet ministers got caught flipping houses on the scheme and then not even paying capital gains tax.

House of Commons

Read more: 7 Top Tips for visiting Britain

Abusing the system

Conservative leader David Cameron lost an aide who claimed back the cost of cleaning the moat at his country house estate. Several MPs were getting regular payments from the Fees Office for rent mortgages that didn’t even exist. London MPs, who lived and worked just a few miles from Westminster, were claiming expenses on “second homes” they were then renting out. The fiddle went from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Nor did these abuses of the system simply go on quietly; MPs were openly encouraging each other to take advantage of what was accepted as a backhand way for them to raise their pay. New MPs were even briefed on what they could get away with.

And, lo, the people of Britain, suffering under the recession, high unemployment, a sagging pound and weary of the struggling Labour Government anyway, were not amused.

The highest-profile political figure to topple directly from the institutional corruption was the Speaker of the House. It was the first time since the 1600s that a Speaker had been charged with malfeasance and forced to resign.

Michael Martin, a Glaswegian labor unionist by trade, succeeded the elegant Betty Boothroyd in the revered Speaker’s chair that is above reproach and above politics. Martin stonewalled the investigation into MP practices, defended the practices by himself and his colleagues and harshly resisted calls for his own resignation (which included the loss of significant pension wealth). Martin had been jetting first-class around the world with his wife at public expense and spent £1.7 million refurbishing his grace-and-favor residence while claiming back the expenses of a “second home” in Glasgow. “I didn’t get into politics not to get what’s coming to me,” Martin virulently proclaimed.

Martin spoke explicitly to the motive force behind the greed, subterfuge, and disrespect for the taxpayer represented in the scandal. Government preferment and political power were a plum to be had precisely because one could loot the public treasury. That’s the way it had always been.

Read more: Is this how the Queen communicates with staff?

All parties involved

Not all MPs have been guilty of fiddling the taxpayer, but MPs of all parties have been involved in some level of dubious claims. Understandably, the Labour Party has taken the brunt of the political fallout. The scandal broke “on their watch,” Gordon Brown was very slow out of the gate to understand the scope of abuse and condemn the system, and there was egregious behavior from a high percentage of his own Government.

Labour’s political fortunes, already doomed by the perceived failures of the Brown administration, have sunk to historic lows. June elections cost the party local control throughout the country and placed it in many locales below the United Kingdom Independence Party, the BNP or the Greens. Only one local council throughout the country remains in Labour control.

Gordon Brown, meantime, announced that Parliament could no longer “be run as a gentlemen’s club” and must develop some new rules and some accountability. Of course, part of the problem is that it’s not a gentlemen’s club anymore. In unspecified olden days, when MPs were generally folk who saw themselves as gentlemen, such institutionally justified plunder would have been impossible.

What baffles American observers is the amount of waffling, wavering, and self-justification that has come from MPs who have been indicted by the public for their excesses and abuses of the public trust.

From 89p bath plugs and cases of wine to home cinema systems and new crystal chandeliers, unabashed MPs defended themselves by saying that they were “within the rules,” and thus beyond the just condemnation of press or public. The number of MPs who have claimed just to have “been mistaken” or who claimed not to be too savvy at personal finance beggars the imagination.

Sterling

What about America?

Now, there’s no room for national smugness here. In the States, as in every country on earth, we have our scandals. Here, though, a Congressional perpetrator in ethical and legal disgrace is encouraged to submit a speedy resignation and may expect to be prosecuted in an appropriate jurisdiction—usually with a vengeance for having violated a public trust. Disgrace is pretty instant.

While many MP abuse of the expense system fell far short of what could ever be considered criminal, others did not. Either way, MPs have been amazingly cavalier about their own behavior and quite determined to carry on despite the antipathy of the public, yea, of their own constituents.

Once again, there is serious personal interest at stake. With general elections assured within the year, if they can just hang on, there’ll be a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. Retiring MPs and those defeated in election are given cash, tax-free golden handshake to help them settle back into civilian life (to more than £64,000). And a comfortable pension that depends upon them serving out their term. Disgrace is optional and highly overrated.

Read more: 7 Royal birth traditions you don't know

How long will it last?

For a country already reeling in an identity crisis and sharing a widespread feeling that the nation has lost its cultural and moral compass, the collapse of confidence in the ancient institution of Parliament has been a terrible blow. The country is angry and frustrated. Labour’s prospects in the inevitable general election, whenever it comes, are nonexistent. Even its continued influence as a major party may be in question.

Cheer up, folks. The country, its monarchy and its institutions will survive. Parliament will adapt. And a new Government of whatever complexion will be enviably placed to succeed in the wake of the present political morass. It’s all just a late birth pang of democracy.

All across England, there are pubs bearing the sobriquet The Marquess of Granby. The third Marquis, John Manners, was a popular soldier of the 18th century. He endeared himself to a thirsty public by pensioning off his retiring noncoms with the wherewithal to start a pub. Many were named in his honor. It was a fine financial reward for a career in public service.

Times have changed. Sort of.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments