Mary Somerville: Astoundingly, the woman who eventually would be recognized as a mathematical prodigy did not learn even the most rudimentary math until she was a teenager.

The history of Oxford University, Sommerville College, and the woman who inspired it, the Scottish science writer and polymath, Mary Somerville.

Walk down the Wood-stock Road in Oxford, and you will come to Somerville College, known as the college of prime ministers (Margaret Thatcher and Indira Gandhi) and novelists (Dorothy Sayers, Rose Macaulay and Iris Murdoch).

The college also has earned a reputation for turning out scientists, including Dorothy Hodgkin, winner of the Nobel Prize in chemistry. In fact, 40 percent of today’s undergraduates go into science careers.

This focus on science can be traced directly to the earliest foundations of the college. Carved into the wall to the right of the school’s main entrance is the Somerville coat of arms and motto, both adopted by the college from the family of its namesake, Mary Fairfax Somerville, renowned as “The Queen of Nineteenth-Century Science.” Inside this wall, Mary Somerville’s legacy lives on; outside the wall, her contribution in paving the way for other female scholars has largely been forgotten.

Somerville has admitted men since 1994, but it was founded in 1879 as the first nonsectarian women’s residence hall at Oxford. The choice of Mary Somerville as a namesake represented a preemptive strike against naysayers who derided educated women as unfeminine “bluestockings,” unfit for marriage and motherhood. In fact, 19th-century British doctors feared that the strain of intellectual work would injure women’s supposedly inferior brains and drive girls mad. When Ada Lovelace, daughter of Lord Byron, experienced a nervous breakdown, her doctor attributed her condition to the study of mathematics, which, he said, is “beyond the strength of a woman’s physical powers of application.”

Yet, there was Mary Somerville, who had engaged in the most advanced study of higher mathematics, physics and astronomy right up until her death at age 92. And she was admired as much for her domestic and social graces as for her scientific work. After her death in 1872, the Morning Post had praised her as an example of “how much a woman could and can accomplish in intellectual pursuits without sacrificing of her usefulness in the sphere of home or her feminine dignity.”

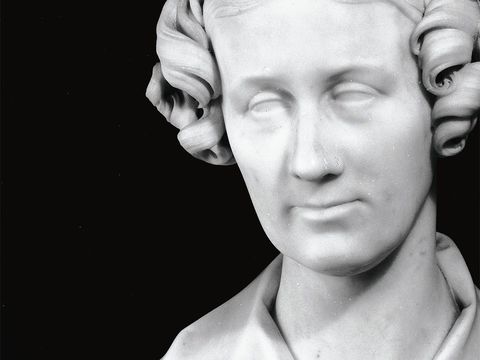

Somerville College owns three portraits of Mary Somerville: John Jackson’s portrait of her as an attractive young woman hangs in the College Hall; another by James Swinton is in the library; and her self-portrait, circa 1820, hangs at the top of the main staircase. A skilled painter who once studied with artist Alexander Nasmyth, she portrays herself seated with quill and paper in hand, an image that foreshadows her success as a scientific writer.

Although she performed some experimental work and was the first woman to present her research to the Royal Society in an 1826 paper on “The Magnetic Properties of the Violet Rays of the Solar Spectrum,” Mary Somerville is best known as the author of four books, most important The Mechanism of the Heavens, used as a standard university textbook for generations of students, and On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, in which she predicted mathematically the discoveries of Neptune and Pluto.

Astoundingly, the woman who eventually would be recognized as a mathematical prodigy did not learn even the most rudimentary math until she was a teenager. Mary Fairfax was born at Jedburgh, Scotland, in 1780, the daughter of a naval officer who was a distant relation of George Washington. Her first experience with formal schooling came at age 10, when her father declared she needed to learn enough writing and arithmetic to keep household accounts. At a boarding school run by a certain Miss Primrose, she was required to memorize entire pages of Johnson’s dictionary while strapped into a steel corset. Not surprisingly, this method failed to inspire a love of learning, and she left after a year. Only when she was 13 did she finally learn some basic arithmetic, which she promptly forgot because of a lack of practice.

The teenaged Miss Fairfax studied all of the subjects thought to be appropriate for young ladies: taking piano, dancing and cooking lessons; and studying landscape painting at Nasmyth’s academy. On a visit to a neighbor to look over some needlework, she was shown a ladies’ magazine that published puzzles in between pictures of the latest fashions, and she got her first glimpse of algebra. Her curiosity was piqued, but she was afraid to ask anyone to explain this new type of math to her for fear of ridicule.

Then, one day when in Nasmyth’s studio, she overheard him recommending to some other students that they study Euclid in order to gain a mathematical basis for perspective. After agonizing over how to obtain the book, she finally asked her brother’s tutor to buy it for her, and then she stayed up all night reading Euclid until her mother noticed that the household’s candle supply was dwindling rapidly. Over her worried family’s objections, she persisted in studying algebra in between her social and domestic obligations.

Read more

IN 1804, at the age of 24, she married Samuel Greig, a distant relation, who, she relates, “had a very low opinion of the capacity of my sex, and had neither knowledge of nor interest in the science of any kind.” Three years later, Greig’s death left her a single mother but also set her free to resume her studies, which she did openly, even corresponding directly with mathematicians, despite the disapproval of many of her relatives. Fortunately, her next husband, William Somerville, another cousin, whom she married in 1812, encouraged her work and served as her amanuensis, copying her manuscripts and acquiring the books she needed.

In line with the Victorian sense of propriety, it was William Somerville who was approached by Lord Henry Brougham in 1827 to ask if Mary would consent to write “an account of the Mécanique Céleste,” the critical work by French mathematician and astronomer Pierre-Simon LaPlace. Understanding LaPlace’s methods and ideas had become necessary for scientific advancement. Unfortunately, only a handful of men in Britain understood his work. Mary Somerville was, according to Lord Brougham, the only person in Britain capable of making this new science available to her countrymen.

Over the next five years, she became perhaps the first supermum, teaching her children in the mornings and writing in the afternoons, despite frequent interruptions by social callers from whom she hid her work. Men, she noted, could devote all of their time to business, but women were expected to maintain a household and social life. The Mechanism of the Heavens, published in 1831, was hailed as a triumph and made Somerville a celebrity. The Royal Society installed a marble portrait bust of her in its great hall in London; she was elected a member of the Royal Astronomical Society and was awarded a civil pension of £200 per year.

Beyond the gardens lie the chapel and residences of Somerville College, still a leading institution in the education of women in the sciences. OXFORD PICTURE LIBRARY/ALAMY

She used her celebrity to advocate for women’s rights. Hers was the first signature on John Stuart Mills’ suffrage petition, and she (unsuccessfully) petitioned London University to grant degrees to women. Her fame has faded, but Mary Somerville’s influence continues to pay off today.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments