The secret of the Peak District's location is not the beauty of its landscapes

Even if you have never visited the Peak District, you have probably seen its dramatic landscape of soaring hills, idyllic villages and serene stately homes because they have been the backdrop for numerous films. Perhaps you remember Colin Firth emerging from a lake in the 1995 version of Pride and Prejudice, or Keira Knightly pondering life from a windswept crag in the 2006 version. If so, you have seen the lake at Lyme Park and Stanage Edge, one of the Peak District’s best climbing spots. If you watched Knightly sashaying through splendid rooms and lovely grounds in The Duchess, you have seen Chatsworth House and Kedleston Hall, where it was filmed. If you saw The Other Boleyn Girl, you have seen Haddon Hall’s medieval rooms standing in for Henry VIII’s palaces. Its courtyard and gardens were the venue for the swashbuckling The Princess Bride, and its castellated roof provided the scary heights from which Mrs. Rochester threw herself in the BBC’s recent Jane Eyre.

The list of Peak District starring roles is so long that there’s a “Peak District and Derbyshire Movie Map” available at tourist information centers. Those who follow it round will not only swoon at the lovely countryside, but marvel at the art collection and fountain at Chatsworth, the Adam interiors at Kedleston, the clocks and tapestries at Lyme and the medieval kitchens, Elizabethan gallery and terraced gardens of Haddon. And at some point, most people will ask: Why here? Why are so many of Britain’s grandest houses clustered together here in the country rather than near its capital?

As with all real estate, the answer is location, location, location. The secret of the Peak District’s location is not the beauty of its landscapes, great though that is, but what lies beneath its surface.

At this southern end of the Pennine chain, limestone butts against gritstone, underground caverns gape and rivers disappear, and most important, minerals form. Copper, iron, lead and coal produced the wealth that built the region’s many treasure-filled mansions. Mining for lead and coal enabled the Elizabethan entrepreneur Bess of Hardwick to build Hardwick Hall. Her descendant, the fifth Duke of Devonshire, used the profits from his copper mines to develop the Crescent and spa buildings in Buxton. Iron and nails produced the fortune that the Sitwells invested in Renishaw Hall and its Italianate gardens.

Because the minerals of the region helped fuel the Industrial Revolution, the Peak District is ringed with cities such as Sheffield, Derby and Manchester. In the days when they were shrouded in smoke from thousands of chimneys, their residents made the Peak District a weekend playground, with energetic young people hiking and climbing its hills, while families came for walks and picnics in its dales. It’s not surprising then that in 1951 this easily accessible region of Derbyshire, plus some neighboring parts of Cheshire and Staffordshire, was designated as England’s first National Park. Today, old railway lines have been converted to become walking and cycling paths; many farmers have created pony trekking facilities, and, as ever, climbers claw their way up rocks, including the four-mile escarpment of Stanage Edge.

The mouth of Peak Cavern, Derbyshire's largest natural cave, in Castelton.

For many, however, the charm of the Peak District is its towns and villages. Buxton with its ancient spa reigns as queen. Most of its elegant buildings date from the 18th century, making Buxton look rather like Bath—an effect that is no accident. The fifth Duke of Devonshire, who owned much of the town, wanted it to rival England’s premier spa, so he built the elegant Crescent of shops and lodgings for visitors and huge stables for their horses.

Buxton sits on a natural source of warm water. It rises at a constant temperature of 82 degrees and is piped to St. Anne’s Well opposite the Crescent. The Romans were among its beneficiaries. Among those that followed were Mary Queen of Scots, who was taken there at the suggestion of Bess of Hardwick, then owner of Chatsworth and wife to Mary’s jailer, the Earl of Shrewsbury.

Mary stayed on the site of the Old Hall Hotel, still a charming hostelry surrounded by buildings that witnessed Buxton’s popularity with the Victorians and Edwardians. The largest of these is the Devonshire, created when a huge dome—once the largest in the world—was put atop the Duke of Devonshire’s stables to convert it to a hospital in 1859. With its high elevation Buxton seemed the perfect place to cure pulmonary complaints, and later to heal the injured in the two world wars. Today it is a campus of the University of Derby, which welcomes visitors to take advantage of the students’ work. Those training to be aestheticians operate a spa in the old hydrotherapy rooms, while the restaurateurs of the future offer gourmet lunches at very low prices in an elegant restaurant just under the dome.

.jpg)

The glass houses of the Winter Garden, just behind the Opera House, are a year-round centerpiece of Buxton's 23-acre Pavillion Gardens.

Buxton is in the White Peak—which is actually pale-gray and called after the underlying limestone from which most of its buildings are made. Driving from it to Castleton, one of the many villages that are honeypots for visitors, you pass through landscape that rapidly changes from bosky to sere and stark as you move into the Dark Peak, so-named after the blackish gritstone that lies beneath, and that provides the local building material.

Castleton is famous for Blue John—a unique kind of fluorite with bands of beige, apricot, mauve and purple. Large pieces mined long ago were used for decorative urns, the most beautiful of them on display in Chatsworth House. Today, only narrow veins remain, and the mineral is mostly made into small ornaments or set in earrings and pendants. Visitors can go down into the Blue John Cavern, where streaks of the precious mineral will be pointed out. Other show caves round Castleton include Speedwell Cavern, Peak Cavern and Treak Cavern, also a Blue John source.

With its little market square and ancient church, Castleton is tucked under 12th-century Peveril Castle. It’s a steep walk up to the castle ruins, but one that most reasonably fit visitors can manage. This area has lots of other walks, making Castleton a center for both casual ramblers and serious hikers and climbers.

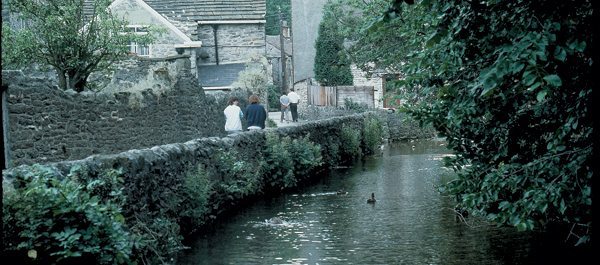

Because Castleton, Buxton and other Peak District towns such as Bakewell and Ashbourne preserve their traditional architecture, it’s easy to imagine them in days gone by: Castleton as a mining and farming village, Buxton as a fashionable spa and Bakewell as an agricultural center thronged with farm folk coming to market—as they still do. But in Tissington no effort of the imagination is needed to see life continuing as it has done for centuries.

Tissington clusters around Tissington Hall. Built in 1609, this Jacobean house and village have always been the property of the FitzHerbert family. With a dreamy duck pond, a pretty church, rows of cottages with bright little gardens and the grand mansion reigning over all, it has an architectural unity almost always lost when modern shops and houses make their mark on old hamlets. Similarly, while some stately homes have a modern museumy air, Tissington Hall feels like an old family home, with photographs of the kids keeping company with portraits of the ancestors. The ninth baronet, Sir Richard FitzHerbert, opens its doors for 28 days a year, typically over Easter and during August, often showing people around its panelled rooms himself. Among them the Library is both spectacular—it has more than 3,000 books—and enormously inviting with its garden views, soft sofas, a woodland frieze and a library table set with tempting volumes.

Tissington is one of the numerous Peak District villages that “dresses” its wells once a year. The “dress” is a board filled with wet clay into which thousands of flowers, petals, leaves and moss are fixed to form a picture, often celebrating a local event or a religious theme. Tissington dresses all six of its wells on Ascension Day, which typically falls in late May, and the Hall is always open to visitors for the occasion. Other villages choose different days for their well-dressing, so throughout the summer Peak District visitors are likely to come upon a flower-decked well or two. (To make sure of seeing one, check the dates at www.welldressing.com.)

Another common sight in Peak District towns is the weekly market. Chesterfield’s market dates back to 1204. Today brightly striped awnings cover scores of stalls on Monday, Friday and Saturday. Bakewell’s market takes over the town every Monday, and includes not only food, clothes and hardware stalls, but live animal sales. Leek has its market on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday plus a fine food market once a month. Among the regional delicacies to look out for are the pancakelike oatcakes often served with breakfast. In Bakewell, look for the famous puddings and its less well-known but very good pork pies. Ashbourne’s specialty is a delicate lemony gingerbread quite unlike the dark gingerbreads typical elsewhere in England.

On market days, towns are thronged with bargain hunters. Indeed, visitors come to the Peak District for many reasons: to enjoy the walking, cycling and climbing, to visit the otter and owl park in Chapel-en-le-Frith, to see the twisted spire of St. Mary and All Saints Church in Chesterfield, to visit the Royal Crown Derby factory in Derby or the Denby Pottery near Ashbourne, to see the Christmas celebrations at Castleton or the illumination at Matlock Bath in autumn when the town puts on spectacular tableaux of colored lights. And of course then there are those stately homes packed with treasures and surrounded by lovely parks and gardens.

Few national parks anywhere offer the sheer variety of ancient and modern, town and country, outdoor and indoor, historical and contemporary attractions. No wonder The Peak District National Park is Britain’s most popular with 22 million visitors a year.

Comments