Conversing with “Mr. Carol”

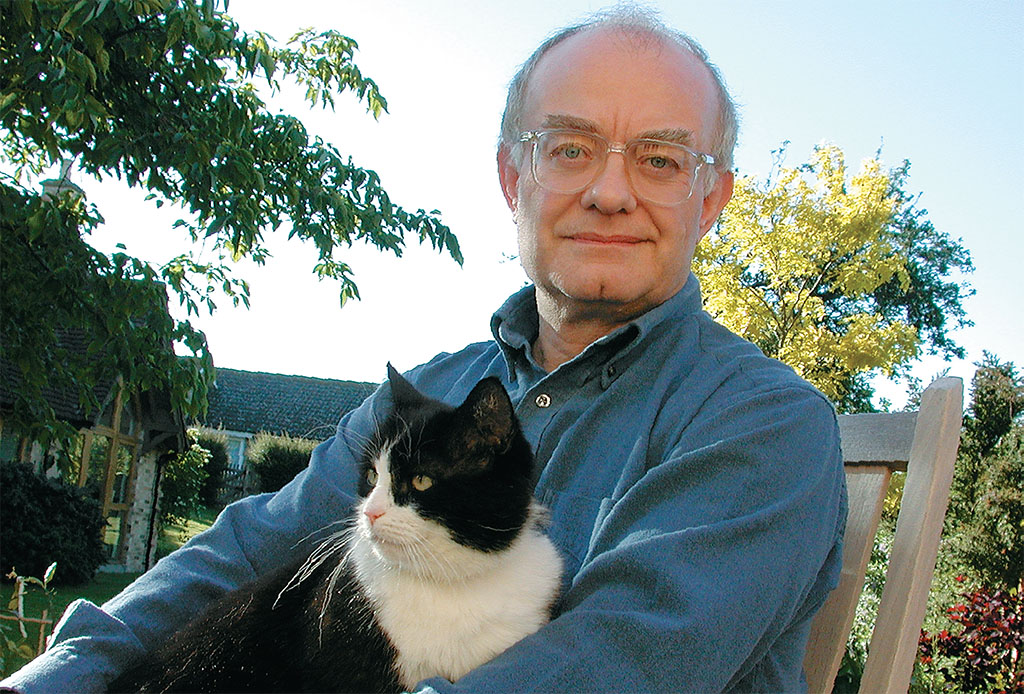

[caption id="JohnRutter_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF COLLEGIUM RECORDS

Alongside Santa and Charles Dickens, the name of composer, conductor and arranger John Rutter has become synonymous with the Christmas season. He wrote his first carols, including “Nativity Carol” and “Shepherd’s Pipe Carol,” while still in his teens. Others, like “Donkey Carol” and “Star Carol,” are firm favorites of the Yuletide repertoire, and just about everywhere you’ll hear his jolly, tuneful songs.

His varied canon also encompasses large and small choral works: “Gloria” (1974), the introspective “Requiem” (1985), joyful “Magnificat” (1990) and popular “For the Beauty of the Earth” (1980). There’s orchestral and instrumental music, children’s operas and scores for TV. The four volumes of Carols for Choirs, which Rutter edited with Sir David Willcocks, are used worldwide, and he has taken his pen to the new Oxford Choral Classics series, Opera Choruses (1995) and European Sacred Music (1996).

These days, when not dashing about the globe conducting, he concentrates on composing, though no longer for commission, which he found to be “a treadmill.” He runs his own professional choir, The Cambridge Singers, and recording company, Collegium. When we speak, he has recently returned from Birmingham and the 25th anniversary concert of the National Youth Choirs of Great Britain; he is about to head off to conduct at Carnegie Hall, a favorite venue where many of his most famous works have been premièred. I catch him at his home near Cambridge.

Given his achievements in such a wide range of musical output, does he mind his early typecasting as “Mr. Carol?”

“No, I really don’t, because I sincerely enjoy Christmas, the time for families, friends and for the music associated with it,” Rutter says. “And, my goodness me, it’s nice to be associated with something happy!”

He has written fewer carols in recent times, but his latest album, featuring The Cambridge Singers working with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Farnham Youth Choir, is A Christmas Festival (Collegium Records). “It includes new compositions of mine and other people, and old favorites in a new guise. There’s the carol I wrote for the Royal Family on Her Majesty the Queen’s 80th birthday, recorded for the first time,” he says enthusiastically.

While some may underrate carols, perhaps for being hummable and accessible, Rutter has been a fan ever since he sang them in his school choir. “The carol is a small art form that isn’t greatly written about or greatly thought about,” he says. “Perhaps it’s like the little wildflower growing by the roadside that isn’t as spectacular as the big, showy flowerbed, but it’s very much part of our musical and literary culture. Carols have a very long history; they are the oldest form of vernacular sacred music we’ve got. Of course, not all are sacred—wassail carols had nothing to do with religion!

[caption id="JohnRutter_img1" align="alignright" width="299"]

“And, my goodness me, it’s nice to be associated with something happy!”

But carols were the first things to be sung in the vernacular in the pre-Reformation Church. It was very common in the 15th and early 16th century to sing them half in English and half in Latin.

“I’ve a feeling we’ve always had a soft spot for them in our national culture,” he continues. “They were often associated with dance rhythms: You danced a carol—the derivation is a ‘carole’, which is a round dance. So it was always something rooted in popular observances of times and seasons and points in the Church’s year. And it’s always a miniature, a pop song length, even going back to the Middle Ages. A present day pop-song writer would recognize many characteristics: There’s usually a hook, a little melodic phrase that comes over and over; there’s often a refrain or chorus, and across the verses there’s a strophic repeating structure.

“I think it’s a rather lovely art form, not just for the music but actually for the words,” Rutter adds. “Some of our loveliest carol texts go back to the pre-Reformation era: ‘There Is No Rose of Such Vertu,’ or ‘I Sing of a Maiden That Is Makeles’—texts like that are just jewels of poetry. Composers great and small have been attracted toward carols, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Walton and Benjamin Britten with his lovely ‘Ceremony of Carols.’ Not too many new carols are being written right now; I wish there would be.

There was a rediscovery of medieval texts back in the 1960s and that impetus has slightly dried up, but I’m sure the carol will not die out: It is something that people still love.”

John Rutter was born in London in 1945. Although his parents were “not particularly musical,” he showed a strong inclination from an early age to pound away on the family piano, singing to his own accompaniment. “My parents were rather astonished,” he recalls. “But I never received anything but warm encouragement. Then at school the light really went on in my head. We would sing ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ at morning assembly and I remember even as a 4 or 5-year-old absolutely loving singing together with other people and listening to the piano play. It just seemed to be something magical, something special. I knew that music in some way was going to be my life.”

He became a chorister at Highgate School, North London, where director of music Edward Chapman spotted his talent and further encouraged him. It was a hotbed of musical activity, and soon Rutter was composing, just like his fellow chorister John Tavener. The choir performed outside of school, too, singing on the original recording of Britten’s “War Requiem” (“a great experience”) and in “Carmina Burana” at the Proms when he was just 11. “Nobody explained to us what the Latin words meant, which is probably just as well because they’re a bit naughty,” he laughs. The experiences of his school days inspired a real taste for music making and audiences, and he later wrote that Chapman “gave us the confidence to be true to ourselves. He taught me the importance of words in music, and somehow imparted his belief (never discussed) that music was fundamentally spiritual.”

Rutter pursued his musical studies at Cambridge University, having gained a place at Clare College. He was taken under the wing of another mentor, David Willcocks, organist of neighboring King’s College, who heard he had been composing, and asked to see some of his work.

“I went trembling like a leaf to his very grand rooms in King’s College and, without a word, he turned over the pages of the pile I’d brought, including some Christmas carols,” Rutter says. Will-cocks was sufficiently impressed to persuade Oxford University Press to take a gamble on this new talent; they agreed and have been his publisher ever since. “It was a remarkable day in my life and Sir David Willcocks is another person to whom I owe a big debt,” he says. “He enabled me to make the leap from aspiring composer to published composer when I was still only 20.” Willcocks also invited Rutter to join him editing the second volume of Carols for Choirs after his co-editor on the first volume, Reginald Jacques, died.

Carols, with their simplicity and singability, were a natural form of expression for Rutter, though it appeared unfashionable early in his career. “In the 1960s and 1970s there was an almost Stalinist orthodoxy in compositional circles,” he reflects. “If you were a serious young composer you were supposed to write 12-note music which to many people was—and remains—rather hard to listen to. And if, God forbid, you actually wanted to write a tune you were in terrible trouble! That’s not so now, but there was very much a party line in those years that I didn’t fit. The music I wrote tended to be fairly upfront, fairly straightforward to listen to and perform. I believe in straightforwardness in music as in life. I never had the ambition to write very complex, convoluted music that could only be appreciated by a small minority. I left that to others.”

[caption id="JohnRutter_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

COURTESY OF COLLEGIUM RECORDS

Unperturbed about conforming, he flourished at Cambridge, where he stayed on to research a doctorate focusing on the divergence between high musical culture and mass musical culture in the 19th century. The thesis remained unfinished as his compositional work took off and (“my ignominious failure to deliver a Ph.D. notwithstanding”) he served as director of music at Clare College from 1975 to 1979. The period was one of the happiest in his life. Clare had moved in 1972 from a single-sex college to mixed, bringing soaring sopranos into the choir. Rutter reveled in developing its success and being part of the choral tradition that is among the university’s great glories.

Even now, he says, he and his wife love to wander around Cambridge, his spiritual home. “You can walk from one chapel to another—any day of the week there is a choral evensong—and have a series of musical and liturgical treats.” It remains forever part of his mental sound-landscape, just as church music has always been a part of his life. On the popular BBC Radio program Desert Island Discs in 2005, he chose Harold Darke’s setting of Christina Rossetti’s “In The Bleak Mid-Winter,” recorded in 1962 by King’s College Choir and directed by Willcocks, as one of the records he’d like to have along if he were a castaway. The iconic performance is among his favorite carols (“I wouldn’t want to say that any one carol is the favorite”) and neatly brought together his association with Christmas, Willcocks and King’s.

Rutter eventually resigned his director of music post because of the flood of invitations he was receiving to compose and also guest conduct abroad. America, rather less concerned than Britain by diktats of musical fashion, particularly welcomed him—the “Gloria” received hundreds of performances in the late 1970s, the “Magnificat” was written for Carnegie Hall—and in due course he enjoyed being made an Honorary Fellow of Westminster Choir College, Princeton, alongside Willcocks.

This year he is celebrating his 20th season of conducting at Carnegie Hall, though he still tries not to think about all the illustrious performers who have trodden its stage before him lest his right arm becomes paralyzed by fear. He enjoys the openness of American audiences, even if applause halfway through a performance can be disconcerting. “But it shows that they are having the same kind of spontaneous thrill you might at a baseball match and I think it’s great. Beethoven would have loved it. I’ve always found that both audiences and performers in America are possibly more in touch with the deep and spontaneous emotions of music, the thrills and spills and excitement.”

He is also a little envious of the vast network of choirs in America, which largely exists because of greater religious observance than in the UK. Britain still boasts a unique cathedral choir tradition, however, and he sees choral singing returning to state schools “after going through a slightly dark night” when morning assemblies all but vanished. The government-funded “Sing Up” program is encouraging more music-making in schools, and Rutter also does his bit with “Come-and-Sing Days” at various venues, when everyone is welcome to a day’s singing regardless of their experience. He loves choral music for its inclusive nature. “There’s something for everyone. Not everybody can be skilled on an instrument, but almost everybody has a singing voice,” he says. “The sense of being part of a choir is a thrill unlike any other. Choral singing connects you with your inner soul.”

It’s an uplifting outlook, and when I ask about motifs or themes that have engaged him throughout his career he replies: “I would not say that there is any one central theme to my work. But what people do say is that there seems to be something very positive, hopeful and optimistic. With the music I write there is a sense that even if it’s fairly dark, there is light at the end of the tunnel. Generally speaking, I’ve written things that look on the brighter side of music, and I leave it to others to do the angst and the turmoil.” For the latest information on John Rutter and The Cambridge Singers’ CDs and recordings, including A Christmas Festival, visit www.collegium.co.uk.

Comments