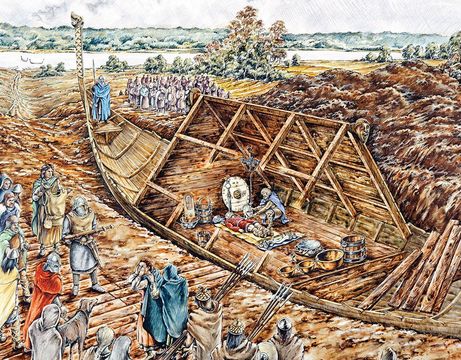

The Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo was one of the most important archaeological finds of the 20th century. Today, visit a reconstruction at the site.PETER DUNN, ENGLISH HERITAGE GRAPHICS TEAM

Take a trip through English history, from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066.

The “English shires” is such a richly evocative term, summoning pastoral idyll, merry old England, solid values, and tradition. “What will they think in the Shires?” news reporters ask with an ironic curl of the eyebrow over the latest trendy urban idea.

Of course, the shires are also physically real, from Gloucestershire to Lincolnshire, Leicestershire to Yorkshire: part of the modern county fabric, of administration, order and identity.

Given such tidiness, it may seem a curious irony that “shires”— from Old English scir—were invented in the so-called Dark Ages of the country’s history, that tribe-torn, unruly period between the withdrawal of Rome’s legions in AD 410 and the crushing fist of Norman Conquest in 1066. Strange, too, that such a “benighted” era invented the very idea of England as a nation, defined its boundaries and worked to unify it.

Or is it? Scratch the proverbial surface and the Anglo-Saxon chapter of England’s history is not such a dim and distant world, rather it’s deep in the cultural weave and weft of the country’s life to this day.

The Staffordshire Hoard, unearthed in 2009, had lain hidden not too far beneath the surface since the 7th century and it stirred renewed interest in Saxon times. See them on permanent display at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, and The Potteries Museum&Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent. More than 3,500 items of bejewelled gold and silver, sword pommels, helmet parts and other militaria conjure visions of a world of alpha male warriors, kings and sub-kings slugging their way to dominance—with a strutting peacock lust for exquisitely crafted ornament and hardware. The Dark Ages razzle-dazzled.

Plenty of other relics—and re-creations—around the country bring us closer to the Anglo-Saxons and what they did for England, too.

Maybe begin on the southeast coast where the replica Viking ship Hugin stands atop the cliff at Pegwell Bay, Kent, recalling the arrival of the Saxon warrior brothers Hengist and Horsa in AD 449. The Saxons had first come to Britannia as hired mercenaries during Roman rule and after the legions were recalled to Rome, the Celtic chieftain Vortigern, fearing threats from the north by Picts and Scots, invited the siblings and their compatriots to help him. They came “like wolves into the sheepfold” the 6th-century writer Gildas chillingly recorded.

Very soon more Saxons, as well as Angles, Jutes and Frisians, from northern Germany, Holland and Denmark were pouring in and spreading west and north, attracted not least by lush land for farming. They expelled, absorbed or enslaved the native Britons, imposed their language and in time considered themselves the rightful natives. By the end of the 6th century the Anglo-Saxons held the east and south, with the Britons hunkered down north of Hadrian’s Wall and west of the Severn and Wye valleys. Here then, with a few tweaks, were modern England’s boundaries drawn up!

For a taste of early settler life, visit West Stow Anglo-Saxon Village in Suffolk. Around 60 people lived here and some of their dwellings have been reconstructed, with thatch, oak, wattle and clay.

Excavated burials also provide rich insights into Anglo-Saxon ways. Consider, for example, the dozens of brooches and information supplied by grave goods, exhibited at the Corinium Museum, Cirencester in Gloucestershire. These come from a cemetery near Lechlade where 199 graves revealed two phases of burial, 450–600 and 7th/early 8th century. Alongside gleanings regarding food, fashion, health and trade, we see how the pagan beliefs of early Saxon settlers became colored by Christian leanings. Later inhabitants seemed to practise a hybrid religion, being buried in an east–west Christian orientation, yet also following pagan custom in taking jewellery and tools with them into the next world.

The 9th-century baptismal font at the Priory Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Deerhurst, is the finest in existence—guarded by an unidentified beast. Via Sian Ellis

Indeed, Anglo-Saxon England negotiated a crucial religious crossroads. At first, the pagan invaders—we still speak the names of their gods in Tuesday (Tiw), Wednesday (Woden), Thursday (Thor)—pushed Christianity (which had taken root in Roman times) to the fringes of Britannia. Yet in the end, they converted, and this story is told in a living legacy throughout the country.

Add St. Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury, to your Saxon map of England: its origins date from Augustine’s evangelizing mission on behalf of Pope Gregory the Great in 597, marking a significant rebirth of Christianity. Today, of course, the ruins are part of the Canterbury World Heritage Site, which also includes the cathedral, the Mother Church of the Anglican Communion.

Elsewhere, sparks of Christianity had never been extinguished and burst into fresh flames. In the 7th century, King Oswald of Northumbria invited monks from Iona to convert his people. Aidan established his monastery on Lindisfarne, where, in the 8th century an artist monk painstakingly created the Lindisfarne Gospels, dedicated to St. Cuthbert. This beautifully illustrated manuscript is now held by the British Library (have a peek via the online gallery) and its blend of artistic styles, Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Roman, Coptic, Eastern, illustrates just what a cultural melting pot Northumbria was.

The remains of at least 250 Saxon churches are known in England and it’s worth looking up a few. St. Andrews Church, Greensted in Essex, is the world’s oldest wooden church, with timber dating back to circa 1060; it remains a place of regular Sunday worship today. Seventh-century crypts sit below Hexham Abbey, Northumberland, and Ripon Cathedral, North Yorkshire. Or drop into St. Laurence in Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire, the epitome of simple, narrow, stone Saxon church building.

Two favorites may be found close together at Deerhurst in Gloucestershire. Odda’s Chapel, one of the most complete Saxon churches in England, displays characteristic “long and short” patterned quoins and was only rediscovered in 1865, having been subsumed into a farmhouse. The nearby priory church of St. Mary the Virgin features a trove of Saxon highlights, including typical 10th-century double-headed, triangular windows, beast-head carvings and a peerless 9th-century font complete with Celtic trumpet spiral decoration.

Differences between Roman and Celtic Christian Churches were largely settled at the Synod of Whitby in 664, and in future the English kingdoms could be united under one primate. This growing sense of a collective “Englishness” was further consolidated by “Father of English History” the Venerable Bede (673–735), who toiled in the monastery at Jarrow.

So, head to Jarrow, St. Paul’s Church and the Bede’s World visitor attraction, to celebrate the scholar-monk’s achievements. He wrote more than 60 works and his masterpiece, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People), completed in 731, is acclaimed for inventing the idea of the English as a single entity. It is also the first work of history in which the AD system of dating is used.

Of course, the drive toward nationhood was not straightforward. The Staffordshire Hoard confirms that early Saxon England was a complicated patchwork of squabbling territories ruled by kings, sub-kings and over-kings—bretwaldas. The late 10th-century epic poem Beowulf, written in Old English, also paints a vivid picture of warrior heroism. Tour the site of Sutton Hoo, in Suffolk, where eerie mounds yielded the sensational martial artifacts of a 7th-century ship burial, probably the tomb of King Raedwald of East Anglia. There’s a compelling full-size reconstruction of the burial chamber there, original and replica finds, and London’s British Museum displays many further discoveries, including an iconic helmet and facemask featuring dragon and boar heads.

Power struggles saw East Anglia dominant, and then other large kingdoms asserted themselves: Northumbria; Mercia, based in the Midlands where the Staffordshire Hoard was found; and Wessex in the southwest. Eventually, a unified Aengla Land emerged, galvanised by the need to join forces against the threat of invading Vikings.

Key figures on the way to unifying Saxon tribes and to beginning centralized systems of government include Offa, the ruthless 8th-century King of Mercia—readers of British Heritage may already be inspired to walk the earthwork dyke he built bordering Wales.

Another was Alfred the Great of Wessex, who spearheaded efforts to repel Viking raids in the 9th century.Wander his capital, Winchester, and you will find the grid pattern of streets is of Saxon origin. Until Alfred’s time, communities had focused on village and farm, but he promoted a system of fortified settlements or burhs—hence our word for borough. Many grew into thriving towns and cities; you’ll walk in Saxon steps around Oxford for example. Alfred also organized his army on a rota basis and built new, fast ships for his navy.

Aside from defence, Alfred set about codifying the English legal system and improving literacy. He was patron of the patriotic Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and he had translations made of books “most needful for men to know” from Latin into Anglo-Saxon. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has some superb period treasures the star of which is the gold, enamel and rock crystal Alfred Jewel: thought to be the handle from an aestel or pointer for following text. Alfred distributed such aestels with copies of his translation of Pope Gregory’s Pastoral Care.

A further breathtaking exhibit at the Ashmolean is the Crondall Hoard of coins, marking the reintroduction of coinage into the country two centuries after the Romans departed. Anglo-Saxon England successfully worked towards a single standard of coinage, not to mention a highly organized tax system. Then, as now, not everyone was pleased!

Alfred styled himself “King of the Angles and Saxons,” but in truth it was his grandson, the audacious soldier and administrator Athelstan, who is reckoned the first real King of England 925–39. The English monarchy was made. And would be unmade many a time.

Viking threats continued to plague, but Anglo-Saxon England had become a rich cultural society and very sophisticated for the times in terms of government. Those shires that divided the whole country into administrative units by the early 11th century, though they would later be called counties, essentially lasted until local government reorganization in the 1970s.

And yet our Anglo-Saxon world would be rudely ripped apart in 1066. William the Conqueror believed he had a right to England, and if not right then might would make it his. One story says that the Normans wiped the Anglo-Saxons and their culture from the face of England, replacing them wholesale with new ways.

Another version avers that the conquered and the best of their systems were assimilated by the conquerors. Certainly, if you dig just a little you will soon appreciate the tenacity and longevity of the Anglo-Saxon legacy. In language terms the Normans might impose a different “royalty” on the “country,” but Old English persisted as a peasant vernacular—we still say “kingly” and “land.” There are pork and pig, mutton and sheep, “Frenchified” and Old English ways of speaking. From town planning to place names, from religious heritage to the naming of “England” itself, the Saxons are still at large.

Mapping Saxon England

Explore England’s towns and landscapes and you really can follow in the steps of the Anglo-Saxons. They gave names to so many places that exist to this day—all you need to know is a little Old English (OE) to unlock the secrets of the original settlements.

England—Aengla Land—means “land of the Angles,” of course, and East Anglia is the name of the area occupied by East Angles. South Saxons, Middle Saxons, East Saxons are recalled in Sussex, Middlesex, Essex.

Anglo-Saxon ceaster, meaning a Roman fort, abounds where former Roman fortified settlements existed: so Romano-British Durnovaria became Dornwaraceaster or modern Dorchester. You’ll be hot on the heels of Saxons as well as Romans in Chester and Gloucester, too.

Happen upon a place whose name echoes OE wic or ham and you’ll know it has ancient pedigree as a settlement/trading centre or village. Ipswich and Chippenham, for example. If your destination ends ing, then it was the place of someone’s followers, maybe Hastings or Reading. Add ing to ham and Nottingham springs to life: once the “homestead of Snot’s people” (over time the “s” has dropped). But take care with the clues: the ending of Buckingham derives from hamm, which indicates it was “land in the river-bend” of Bucca’s people.

Tun (now town or –ton) meant “farm” and subsequently a village; locations ending in stow were meeting places; and burh was a fortified settlement, like Shrewsbury or Canterbury.

Or give directions the descriptive Saxon way: look for the leah (wood/glade) of Bisa and Budda in Bisley and Buddleigh, and the hill (OE dun) of the huntsman in Huntingdon. And doesn’t the Anglo-Scandinavian combination of dun and holmr (Old Norse for island) still perfectly describe Durham perched on its hill in a bend of the River Wear? But where, now, is the hurst (clearing) in Sandhurst?

People knew their place in Saxon society and so can you. Walh described foreigners—and specifically Britons (hence “Welsh”). So a place like Walton was the village of the foreigners. A free peasant was a ceorl and so Charlton was a town of churls and Charlecote a cottage of them. Find the noble alderman at Aldermaston and the beekeeper (bicere) at Bickerton. And just imagine the bucolic farming landscape conjured by shepherds at Shepperton and goats at Gatwick!

Saxon treasure trail highlights

NORTH

Bede’s World, Jarrow - Meet the “Father of English History”

Durham Cathedral - Shrine of St. Cuthbert and Tomb of the Venerable Bede

St. Paul’s Church, Jarrow - Part of the monastery where Bede worked and worshipped

LONDON & SOUTH

The British Library online gallery for Beowulf and the Lindisfarne Gospels

St. Andrews Church, Greensted - The world’s oldest wooden church

St. Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury - Marking a revival of Christianity

St. Laurence Church, Bradford-on-Avon - Admire the simplicity of Saxon church building

Sutton Hoo, Suffolk - Ship burial, plus treasures displayed at The British Museum

Viking Ship Hugin, Pegwell Bay, Kent - Commemorating the arrival of Hengist and Horsa

West Stow Anglo-Saxon Village, Suffolk - A flavor of period living

COTSWOLDS & MIDDLE

Corinium Museum, Cirencester - Grave goods reveal their story

Odda’s Chapel, Deerhurst - One of England’s most complete Saxon churches

Offa’s Dyke - King Offa’s earthwork between England and Wales

St. Mary’s Church, Deerhurst - Superb 9th-century font and Saxon features

Staffordshire Hoard - See items on display at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery or The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford - Alfred Jewel, Crondall Hoard and more.

* Originally published in July 2016, updated in Aug 2023.

Comments