[caption id="ADaytoVisitConwyCastleTown_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

SAILING YACHTS BOB BELOW THE MASSIVE RAMPARTS and tall, slim turrets of a castle. A small quay is lined with fishermen’s cottages; walls 20-feet tall run behind the cottages to curve upward, enclosing a bustling little town. Inside the walls, narrow lanes are tightly packed with historic buildings, and streets are lined with museums, galleries, shops, cafes and pubs. Outside, rugged mountains form a dramatic backdrop.

Now this is what a castle town should look like—Conwy, in North Wales.

Conwy is amazingly unspoiled. This is partly because the inevitable modernization has all occurred on the far side of its wide, tidal harbor, at the busy seaside resort of Llandudno. But it’s also because even the most hardened acolytes of progress have been won over by its incredible beauty. In 1826, when the great engineer Thomas Telford built the modern era’s first purpose-designed road, he was forced to cross the Conwy River right at the castle, the only river crossing for miles; refusing to defile the town and its walls, he designed a graceful, crenellated suspension bridge that complemented the castle, then curved his road discreetly around the castle’s base, placing modest new arches through the town wall rather than knocking the wall down.

In 1850 the threat was much greater: a two-track railroad, designed by Robert Stephenson. Like Telford, Stephenson designed his massive bridge to mirror the castle, and pierced the town walls with new arches rather than blowing holes in them. Today the town walls exist almost intact, having been destroyed at only one narrow point, where a 1958 successor to Telford’s road crashed into town. Fortunately, the modern coastal expressway misses Conwy altogether, sliding under the estuary in a tunnel.

All this care has not only kept Conwy looking the way it did when Telford was alive; it also means you can walk the top of its town walls for nearly two-thirds of its circuit. Of course, you will probably want to start with the castle, improbably tall and bristling with towers. Some of those towers project into the sky like pencils, affording terrific views at the price of many narrow stone steps.

THOSE TOWER STEPS MIGHT EXPLAIN why so few seem to have the energy to continue on along the wall. Indeed, the wall-top walk has its own multiple sets of spiral stone stairs and some fairly steep uphill pulls, as the walls climb the lowermost mountain slopes. The walk is certainly exciting, as the walkway is a scant 4 feet wide and is only occasionally railed on its inboard side. It yields continuously changing views over the town on one side and the moors and farmlands on the other, with lovely little surprises along the way—such as the town’s Catholic church planting a little garden along it, complete with stations of the cross.

As British towns go, Conwy is not old. Edward I “Longshanks” built Conwy in six years starting in 1283, a year after his conquest of North Wales. Then as well as now, Conwy was a choke point in transportation along Wales’ northern coast, a rocky projection into the wide and muddy estuary. The town walls provided much needed protection—from the Welsh, as no Welshmen were allowed in or near the town (a prohibition that would stand for 200 years). Conwy was not the only such English colony on Welsh soil, but was evidently the strongest, as it alone went unbesieged through two major uprisings.

‘Start with the castle, improbably tall and bristling with towers that project into the sky’

A modern visitor gets to Conwy the same way as a Victorian tourist: by train or by road. The modern automobile bridge is an attractive but unremarkable structure that partially hides Telford’s carriage bridge, now pedestrianized and in the care of the National Trust. There are several parking lots, but by far the best and cheapest is the lot just outside the walls off the B5106; the easy path enters the town walls through the original medieval gate, with stunning views toward the castle. The railroad penetrates the town walls through a parabolic arch to stop at a tiny passenger station in the heart of town but well-hidden below street level.

The town itself is easily done on foot. The main highway, the A547, passes through town on a pair of one-way streets, to exit the town walls through gates barely wide enough to admit a bus. High Street forms a one-way link between these two, and together these streets form an H five blocks long, all lined with historic buildings. The oldest house in town, Aberconwy House, dates to the town’s first century and is owned by the National Trust. Built of stone with an overhanging post-and-beam second story, this prosperous merchant’s home is furnished inperiod to demonstrate its occupancy through the centuries.

The parish church, however, is even older. Hidden in a wide green within the town’s lower block, it was originally part of a monastery that had otherwise been destroyed to make the castle. Next to these two, Elizabethan Plas Mawr seems positively modern. Built in 1585, it shows how prosperous the town had become under the Tudors; Cadw, the Welsh government’s department of antiquities, has it exquisitely restored and furnished to reflect its original purpose. Behind Plas Mawr is the Oriel Gallery, the home of the Royal Cambrian Academy, which has supported Welsh art for 125 years.

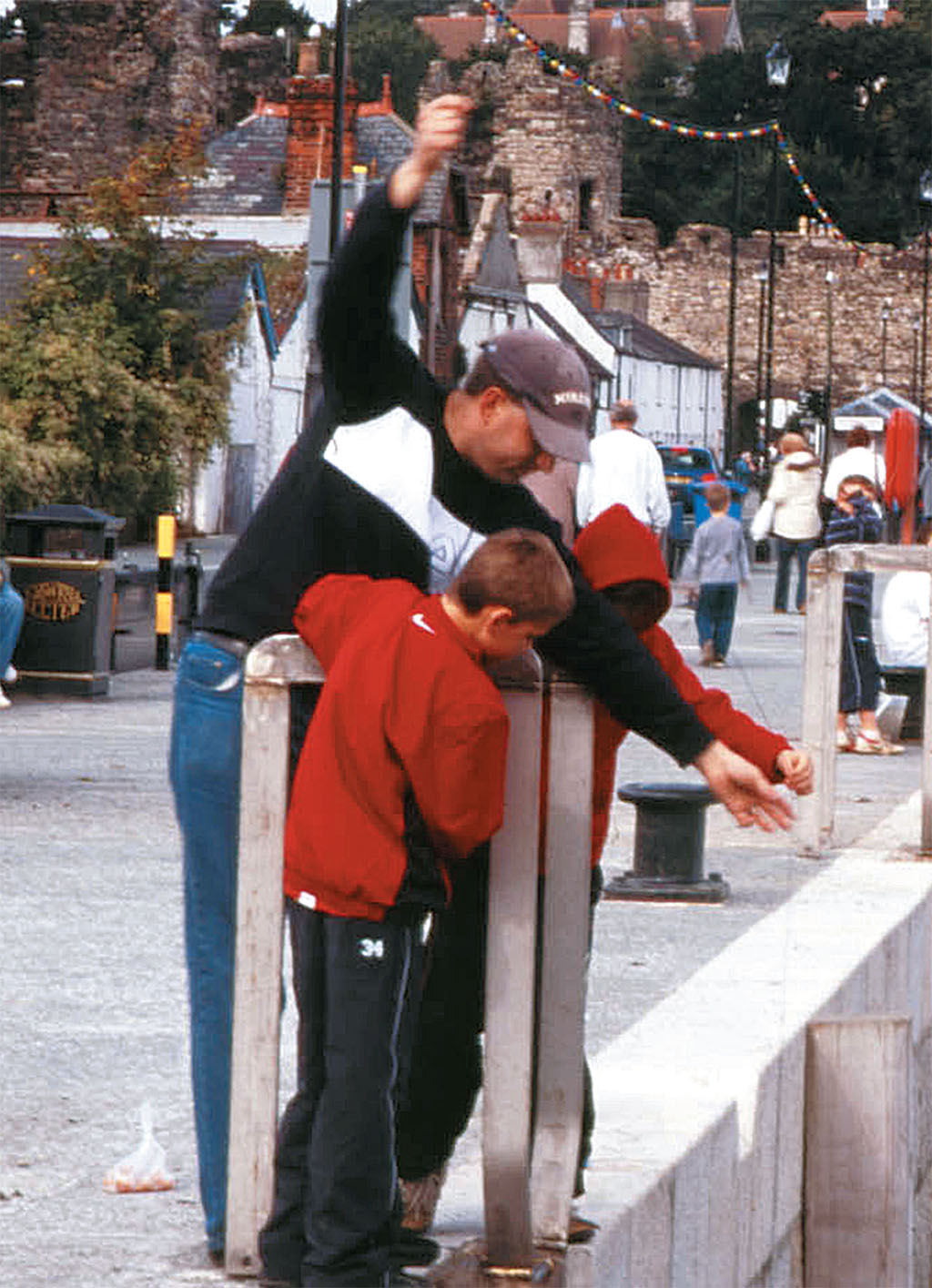

AND THEN THERE’S THE QUAY. High Street drops down to it, entering it through a medieval gate hardly visible from the buildings crowding the town wall. On the left, centuries-old fishermen’s cottages crowd the waterside, including the smallest cottage in Britain according to the Guinness Book of Records, now run as a very tiny tourist attraction by the descendants of the last fisherman to live there. On the right is the Conwy Lifeboat Station, and beside that the Mussel Museum and a memorial to the Conwy mussel trade—plied until the mid-20th century for pearls rather than for food. Views back to the castle are spectacular, as are vistas across the harbor to Llandudno and the bare rock cliffs of Great Orme Head. There is no better place for a final view of the ultimate castle town.

[caption id="ADaytoVisitConwyCastleTown_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="ADaytoVisitConwyCastleTown_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="ADaytoVisitConwyCastleTown_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="ADaytoVisitConwyCastleTown_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

Clockwise from top left: The smallest house in Britain lies tucked into Conwy’s town wall next to the medieval gate leading from the High Street to the quay. Visitors stroll the quay and fish where working boats and pleasure craft tie up next to centuries-old fishermen’s cottages. Conwy’s original 13th-century town walls remain intact around most of the old town, the frequency of their towers an indication of the walls’ strength. The castle and the walls of Conwy that King Edward I built were not to protect the Welsh from attack, but to keep them out of what remained an English enclave in North Wales for 200 years.

Comments