The old whaling port rides high again!

[caption id="ADaytoVisitDundee_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

MARMALADE MAY BE Scotland’s second greatest contribution to the world’s culinary pleasures. Like a fine malt whisky, Scottish marmalade assaults you with massive tongue flavors, then bursts with overwhelming aromatics; like haggis, it’s pungent, a product of a land that likes strong flavors. Unlike either, however, it requires an exotic ingredient from sunny tropical lands—the hard, little, bitter oranges from Seville, Spain. Marmalade could only have come from a great seaport, a crossroads where even this obscure and nearly unsaleable citrus could be found. That seaport was Dundee.

Dundee is a tightly packed city of 141,000 sitting on the north bank of the River Tay’s broad tidal estuary, 55 miles north of Edinburgh. The 20th century was not kind to it, and it fails to impress upon first sight. As you approach Dundee by road from Edinburgh, the 1.5 mile long Tay Bridge gives you broad views towards the city. Here you’ll see Dundee jammed below two rugged little hills, the extinct volcanic cones of Balgay Hill and Dundee Law. This view is spoiled, however, by council (public) housing skyscapers ostentatiously hogging the skyline on your right. The tightly-packed buildings ahead of you are all Victorian and modern. Although Dundee dates back to the 12th century as a royal burgh, little of that dim past has survived in its fabric.

Now that you’ve got the bad stuff out the way, you can start appreciating Dundee’s many good points. For in front of you is a fascinating and lively small city whose history, although short, is rich and colorful. Dundee is a boom town of the Industrial Revolution as well as a bust town of the 20th century—but the bust period has visibly ended, and Dundee is bustling once more.

Start by turning left at the base of the bridge, heading towards Dundee’s riverside. Directly in front of the railroad depot is Discovery Point, home to the Antarctic exploration ship RRS Discovery, Dundee’s proudest achievement as a seaport and shipbuilder. Built in Dundee in 1901, Discovery was the last wooden three-masted ship constructed in Britain, and was specifically designed to thrive in dense ice packs. Robert Falcon Scott commanded it in the ground-breaking British National Antarctic Expedition of 1901 to 1904 (with future Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton as his Third Mate) during which Scott’s company collected a massive trove of data on Antarctic weather, landforms, biology and geology. Following the Antarctic Expedition, Discovery had a long and varied career. It participated in the rescue of Shackleton and his crew after their epic trek through Antarctic seas in a lifeboat, served as an Antarctic research vessel on various trips as late as 1931 and ferried supplies to the White Russians during World War I. Finally, it spent a long retirement as a Sea Scout Ship. In 1986 the fully restored ship returned to its home port of Dundee to take up permanent harbor in a dock built just for Discovery. You can tour the ship, outfitted above and below as it was for the 1901 expedition, and enjoy the large and well mounted museum dedicated to it immediately adjacent, an unusual glass-sided octagon with a Victorian feel.

[caption id="ADaytoVisitDundee_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="ADaytoVisitDundee_img2" align="aligncenter" width="121"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="ADaytoVisitDundee_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

To your right the riverside continues as an attractive landscaped drive as far as the railroad bridge, itself an impressive structure and well worth your time. Here you’ll find memorials as well as explanatory plaques. The first attempt at a railroad bridge over the Tay, poorly designed and unable to withstand storm winds, collapsed as a passenger train crossed it in 1879; among the 75 dead was the builder’s son-in-law. Low tide uncovers the stumps of its piers beside the 1887 replacement bridge, a tall, gently curving structure two miles long.

FOR A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE on Dundee’s glory days, visit the Verdant Works, in the old mill district on the northwest edge of downtown (a nine block drive, well signposted). Dundee had originally become prosperous as a whaling port and a center for wool weaving. In the 1820s Dundee merchants realized that this was exactly the right combination for the hot new textile, jute. While we now think of jute as a rope fiber, it can, with sufficient processing, be softened and spun into a yarn to produce an extraordinarily tough cloth. Essential to this process: ample supplies of a light oil, and in the days before petroleum refining this meant whale oil. Initial treatment yielded hessians (burlap in American English), used for a tough shipping bag. Treat it further and it can be woven into a soft-textured but stiff fabric, useful for drapes, upholstery and carpet bags. Jute weaving was Dundee’s dominant industry throughout the Victorian age. The Verdant Works preserves an early jute mill, a handsome large building of great gray stone blocks. Inside, the museum presents the Dundee jute story in a series of exhibits on the original factory, jute growing (in India) and the importance of jute in Dundee (very). With a trip to Verdant Works, the Dundee story begins to come together—a city becoming dependant on a single industry, and that industry increasingly reliant on cheap labor to succeed. Dundee lost its jute industry as Indian merchants learned to weave jute and cut Scotland out of the loop. Surrounding the Verdant Works are the hulks of other massive stone jute mills, some still vacant but many now becoming offices and apartments—useful square footage for an emergent Dundee economy.

[caption id="ADaytoVisitDundee_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

Between these two points lies central Dundee, 20 or so blocks of shops and offices. You’ll find it centered on High Street, pedestrianized with a large square in front of the City Council’s offices. It’s a lively place, filled with shops, street sculptures and bustle. The buildings are fine old Victorian five-story terraces, and interesting courtyards shoot off in both directions. On the western edge (where High Street is renamed Nethergate) is one of the city’s oldest structures, its medieval church with a 500-year-old tower, set in a courtyard and surrounded by a great, curved, reflecting glass wall—the Overstreet Market, housing some of Dundee’s most fashionable shops. One long block to the north of the City Square is the McManus Gallery, housing the city’s collection of Victorian art and artifacts in a striking Victorian Gothic building. Although it’s been closed for refurbishing since 2005, by the time you read this it should be reopened with completely redesigned exhibits on Dundee art, living and environment.

Looming above it all is 570-foot-tall Dundee Law, hard to find but worth the trouble. Covered with meadows and trees, this craggy old hill offers stunning full panoramas from its War Memorial obelisk. From this point, Dundee looks altogether different—a strong, attractive city with a great future ahead of it.

Hanging around Dundee

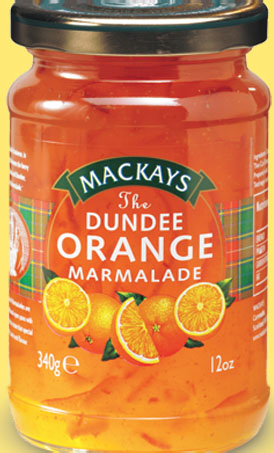

Marmalade. The Keiller family of Dundee invented marmalade, and their white bottles have been familiar breakfast table objects for many years. Alas, Keiller’s Marmalade is now just a brand owned by a former competitor, and the white jars are filled in a Manchester plant alongside clear marmalade jars with different labels. For authentic Dundee marmalade, slow-cooked in open vats, look for MacKays: www.mackays.com.

[caption id="ADaytoVisitDundee_img5" align="aligncenter" width="274"]

COURTESY OF MACKAYS

Discovery Point is owned and operated by the Dundee Heritage Trust. It’s open Monday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. in season, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. in winter, with an admission charge of £7.50 per adult and £20 for a family of four.

www.rrsdiscovery.com.

Verdant Works is also owned and operated by the Dundee Heritage Trust, and has the same Web site and admission charge as Discovery Point; you can also get a joint ticket at a substantial discount. Its summer hours are the same as well, but during the winter it’s closed Sunday to Tuesday, instead of just Sunday.

The McManus Galleries are slated to reopen, with a completely renewed interior, in October 2009. Owned and operated by the City of Dundee, admission is free. www.mcmanus.co.uk.

Dundee Law. This city park is only a short distance north of downtown, but amazingly hard to find in an automobile. Take a taxi. To walk from downtown, find Constitution Street at the northwest corner of downtown, and walk up until it ends as a paved footpath with a church across the street. Go through the church gate at the right and continue uphill one block to Law Road, which you follow uphill to your left.

Comments