[caption id="ADaytoVisitPenzance_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="ADaytoVisitPenzance_img1" align="aligncenter" width="148"]

JIM HARGAN

‘A ROLLICKING BAND OF PIRATESWE, WHO, TIRED OF TOSSING ONTHE SEA, ARE TRYING THEIR HAND AT BURGLAREE, WITH WEAPONS GRIM AND GORY’

—W.S. Gilbert, The Pirates of Penzance

Rowdy, rollicking pirates, gripping weapons dripping with gore—nothing says Penzance more. And the townsfolk know it. Visit it and you’ll be quickly confronted with pirate souvenirs everywhere, special pirate-themed gift shops, pirate cafes, even a pirate ship moored in the harbor and selling, well, pirate stuff. After all, we’ve heard something or another about the “famed Pirates of Penzance,” so why not buy a funny hat with a skull and crossbones to celebrate them?

In fact, those pirates first appeared in Penzance, not in the 18th century, but in Gilbert & Sullivan’s 1879 comic operetta, The Pirates of Penzance, or The Slave of Duty. Librettist William S. Gilbert’s pirates were a band of tenderhearted, orphaned noblemen who valued the Queen’s name above life—except for Frederick, the hero, who was apprenticed to them only because his nursemaid mistook the word pilot for pirate. Gilbert probably chose Penzance (apart from the alliteration) because it was such a silly place to put pirates. To Gilbert and his fellow Londoners, Penzance was just a seaside town at the end of the railroad, the very last place you’d find pirates, other than the figurative kind that run souvenir shops.

Some 130 years later Penzance is still a seaside town at the end of the railroad. It sits at the far western end of the Cornish Peninsula, atop a rocky outcrop that protrudes into sand beaches. In olden times before sea bathing came into fashion, rocky outcrops were all the rage, and would frequently become small harbors with villages climbing the low cliffs above. In this, Penzance was actually a bit backward. During the medieval period it seems to have consisted of a holy site on its protruding headland and some fishing boats dragged up the sand of the adjacent beach—about the only thing beaches were good for in those days. The big local market was at Marazion, 2.5 miles away at the far end of that beach, similarly rocky and host to a large fortified abbey under French control. (More on that abbey later.) Penzance’s fortunes began to change in the 15th century, when Marazion’s abbey was suppressed for being French and converted into a castle, several of whose owners rebelled and were besieged. That’s always bad for business, and merchants shifted the short distance to Penzance. By the 17th century it had been declared a borough, with a royal market and a harbor.

Penzance began to grow during the late 18th century, one of several ports used by the newly industrialized, deep-shaft tin mines being opened in the Cornish hinterland. By the middle of the 19th century, tin exports had made it a small city with 3,000 people, expanded harbors, gas lights and paved streets. Then, in 1859, its railroad finally linked up with the rest of Britain, instantly eliminating its long status as a nearly inaccessible backwater. The new railroad, terminating at the eastern end of Penzance’s docks, was an industrial line that hauled in coal and hauled out tin and fish. Unexpectedly, it also started to haul tourists. In 1879, Penzance’s wood depot was replaced by the current enclosed, four-track building, a hulking structure of gray local stone; today it is still the end of the line, and processes a respectable half-million passengers a year.

By rights, the tourists should have been coming to Penzance for that spectacular beach; with 2.5 miles of the fluffy stuff and a nicely protective dune line behind, it was long enough for its railroad company owners to build 440 beachfront terraces. The railroad, however, had been so intent on carrying tin, fish and coal that they never thought of carrying tourists, despite the success of such towns as Brighton and Eastbourne. As a result, they saved a few pounds by putting the railroad right on top of the dune line, cutting off all beach access—and it remains so to this day, a two-mile stretch of sand reachable only from a path. No matter; there were plenty of beaches nearby, and the type of tourist who could afford such a long and expensive train ride could also afford to hire a carriage.

More important to tourism was the climate. The Gulf Stream bathes the south coast of Cornwall with warm Caribbean waters, so that its mild winters come late, and spring buds come early. At a time when the French Riviera was beyond the reach of the burgeoning middle class, Penzance became the capital of the Cornish Riviera. A new class of resident, uninterested in tin or fish, came to Penzance, built townhouses that climbed the town’s hills in stately lines, and planted palms in their back gardens.

[caption id="ADaytoVisitPenzance_img2" align="aligncenter" width="726"]

JIM HARGAN

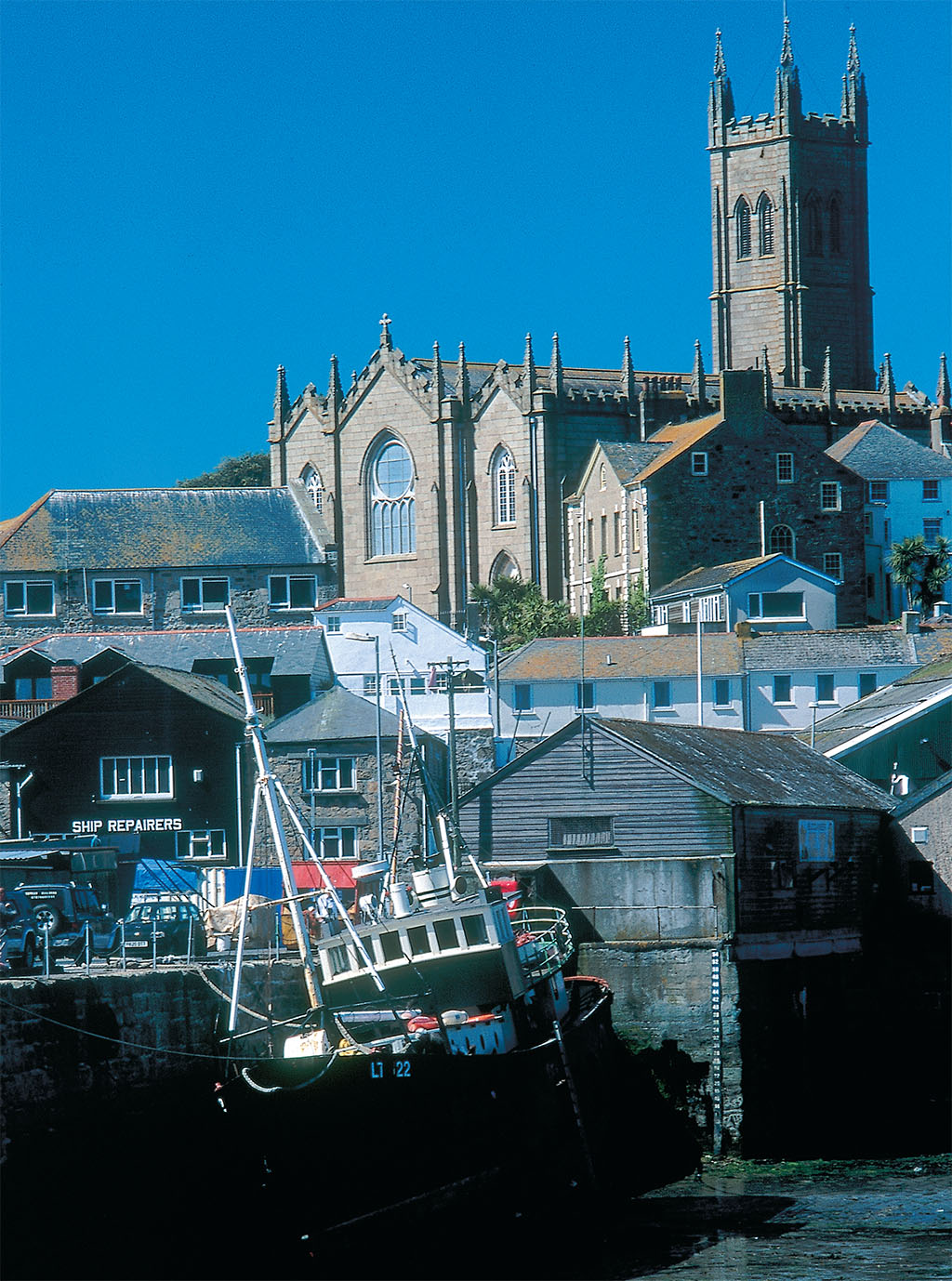

Contemporary Penzance’s glory is its harbor, stretching for a half-mile below the town center. Its uppermost section is now a large car park just behind the train depot. It is where you’ll park if you are driving. In front of you the stone-piered harbor drains dry at low tide, leaving the yachts and fishing boats nicely lined up and perched on sand. Beyond it is the town quay, a tidal wet dock in which interesting boats moor behind the locks, including that pirate-ship-cum-gift-shop. Above looms the ancient hill that gives the town its name, pen (headland) sans (holy), climbed by a long flight of steps. The beautiful church on top, dominating views from the harbor, appears to be medieval but is in fact Victorian Gothic Revival.

From the harbor car park, an arcade takes you a short block through nice shops, then up a floor to Penzance’s commercial center on Market Jew Street. The shops on the opposite side of the street are higher still, and steps lead up to the railed and elevated sidewalk. It ends at the 1840 Market Hall, a grand structure built in the heyday of Penzance’s market, now, alas gone; today it’s a Lloyd’s Bank. Here a convergence of streets marks the site of the market, which predated Market Hall by centuries and would have sprawled down the lanes. Farther on are two superb parks, both laid out in the late 19th century to make the town more attractive to tourists. Penlee Park consists of a great house and garden, donated to the city and converted to a park and museum. Penlee House Museum is devoted to both local history and the works of the major artists who came to this area for inspiration in the late 19th and early 20th century, two subjects that blend wonderfully as the second exemplifies the first. Across the street is Morrab Park, a hidden garden given over to palms and subtropical plants.

The most astonishing and worthwhile site, however, is just outside Penzance, where the beach ends at the attractive (but crowded) village of Marazion. St. Michael’s Mount consists of a large granite outcrop a third of a mile offshore from the village, with a handsome little harbor, and crowned by a massive abbey-castle. At high tide it’s cut off from land, but at low tide you can walk to it on a stone causeway. The abbey dates from Norman times and was converted to a castle in the late 15th century, making it a fascinating blend of religious and military structures from every medieval period, and a few postmedieval periods as well. The small stone village that clings to its harbor dates from the 18th century. Although St. Michael’s Mount is a National Trust property, it remains the residence of the descendants of its 17th-century owners.

Visiting Penzance

Direct trains from London to Penzance leave Paddington Station every hour or two, and take from 5 to 5 ½ hours. The route is one of the most scenic in Britain—through the chalk hills of Wiltshire, along the stunning coast of the River Exe, then across the River Tamar on Brunel’s Royal Albert Bridge, one of the great engineering works of the Victorian age. Seat reservations are strongly recommended even if you are on a Brit Rail Pass, as many trains run with all seats reserved. For schedules and tickets, visit www.nationalrail.co.uk. Nearly the entire town of Penzance is within walking distance of the station, taxis are always available and there’s a car rental agency at the depot.

There are two good sources of online Penzance information: the Penzance Chamber of Commerce’s Penzance Online (www.penzance.co.uk), and the independent World Guides site, penzance.world-guides.com. For St. Michael’s Mount, visit www.stmichaelsmount.co.uk.

[caption id="ADaytoVisitPenzance_img3" align="aligncenter" width="611"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="ADaytoVisitPenzance_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

Comments