Iwrite to you from Glasgow, a thoroughly modern city shaped by the Age of Empire. Here, in a mere century and a half, neighborhoods have been swollen by commercial and industrial prosperity, ravaged by decline and now reinvigorated by sheer determination.

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

WWW.BRITAINONVIEW.COM

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img1" align="aligncenter" width="585"]

©AA WORLD TRAVEL LIBRARY/ALAMY

Entering by train through the city’s Central Station, I immediately felt both Glasgow’s past and present. Above the busy travelers and computerized information boards, the station’s glass ceiling glitters through a tracery of exposed metal beams and joists. This is 19th-century design glorying in its function.

Just outside Central Station are streets named for men who first brought Glasgow commercial success—Tobacco Lords Buchanan, Oswald, Ingram and Glassford—and for the places—Virginia and Jamaica—where they made their fortunes. These merchants imported tobacco from the American colonies and then sold it throughout Britain and Europe. Eventually, they also became involved in the infamous triangular trade among West Africa, the Caribbean and America.

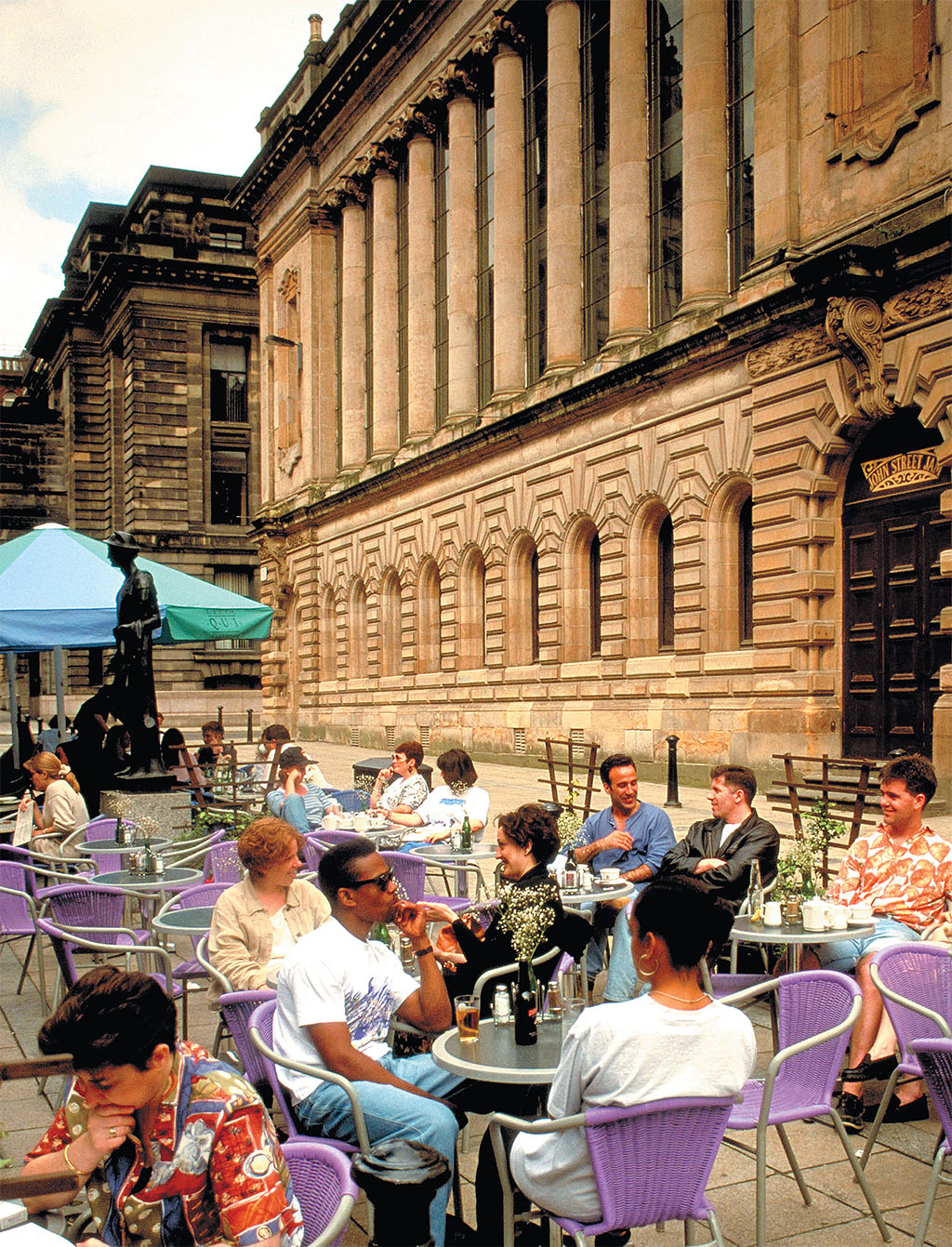

Their wealth built Merchant City, which lies just east of Central Station. Today the 18th-century houses, shops and warehouses have been transformed into trendy restaurants, apartments and galleries. One suspects Glasgow’s pragmatic and enterprising merchants would have approved of this repurposing that has brought their old neighborhood a new vibrancy.

West of Merchant City is Glasgow Centre, which grew up in the 19th century as the city turned its energies to industry. First it manufactured textiles, soap, paper and glass. Later it built ships and locomotives. Workers from the Highlands and Ireland came to labor in these endeavors. Local deposits of coal and iron provided raw materials, and the River Clyde and Atlantic Ocean facilitated the transport of finished goods.

The energy of the industrial age is reflected in the variety of central Glasgow’s architecture. Above the storefronts of chain stores one can see a towering encyclopedia of Victorian styles. Buildings of Scots Baronial, Neo-Baroque, Greek Revival, Neo-Gothic and Italianate design all elbow each other in a friendly competition for space along the streets.

No museum to its past, Glasgow has recently redeveloped large sections of itself, including the eastern end of Sauchiehall Street. Once an unappealing, run-down area, this is now an attractive and well-stocked shopping mall called the Buchanan Galleries.

We had dinner at a nouvelle Mediterranean restaurant on Sauchiehall. The food was trendy, light and tasty. After a week or so of dark pubs and shepherd’s pie, it was a welcome change. This was a cosmopolitan restaurant that you might find in any Western city. The one unusual element in the meal was the generous amount of goat cheese in my salad. This was one salad that didn’t leave me hungry in an hour.

Nearby, the predominantly commercial Buchanan Street has been turned into a pedestrian thoroughfare. Whereas much of Sauchiehall is nondescript at best, Buchanan is a charming mélange of Victorian structures containing interesting stores. Glasgow is a very walkable city, and the central portion of the city, particularly Buchanan Street, is well worth a stroll.

West of Glasgow Centre is a more residential, tree-lined neighborhood that was once home to many of the city’s wealthy industrialists. Developed in the late 1800s as a series of villas and stylish terraces, this area, like the entire city, declined in the mid-to-late 20th century. Today, however, it is being regentrified and slowly reclaiming its former grandeur.

Our B&B, the Alamo Guest House, is a small example of this resurgence. Once down at the heels, the Alamo has been transformed by its energetic owners into the most elegant guesthouse I’ve visited in a British metropolis.

Just outside the guest house doors lies magnificent, rolling Kelvingrove Park, which is perfect for a morning jog or play time with a child. Adjacent to the park, Kelvin Hall houses the Museum of Transport and the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum. The Spanish Baroque buildings look striking—and a little odd—against the lush greenery of the park.

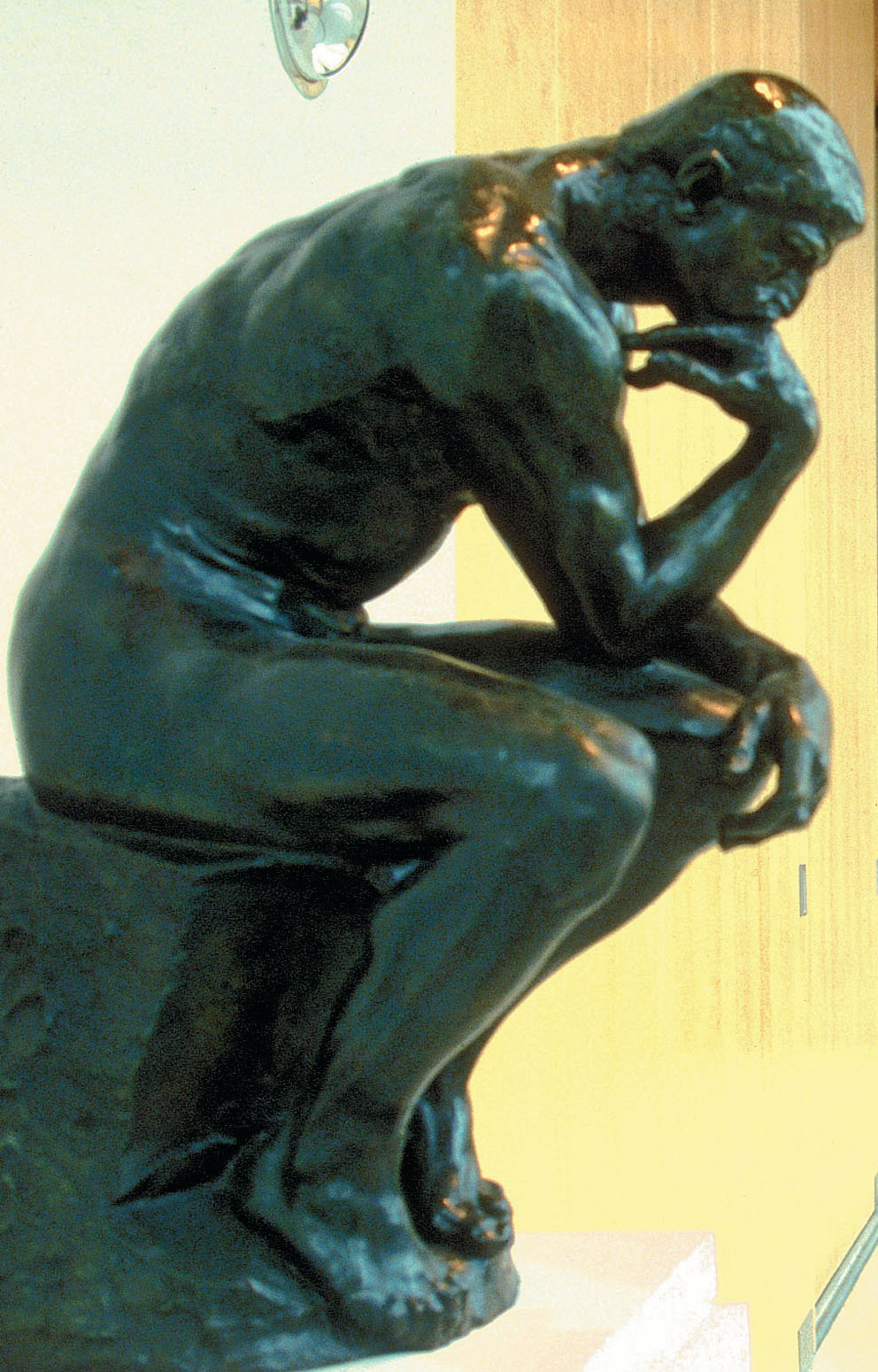

Recently renovated, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum offers exhibits devoted to armor, Egyptology, Scottish history, natural history, even a display on what it’s like to pilot a Spitfire. It also contains some first-rate art, including major paintings by Whistler, Dalí and Rembrandt. The nucleus of the Kelvingrove art collection came from Archibald McLellan, a Victorian businessman who left his collection of more than 400 paintings to the people of Glasgow. The founder of the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, at the nearby University of Glasgow, was William Hunter, a famous anatomist, teacher and midwife to Queen Charlotte, consort of King George III.

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

WWW.BRITAINONVIEW.COM

In the late 1700s, Hunter bequeathed his enormous collection of ethnographic, zoological, botanical and geological material, as well as his coins, paintings and medical paraphernalia, to the University of Glasgow. About a century later, when the university moved to its present location, just west of Kelvingrove Park, his collection came too. I enjoyed the gallery’s rooms of atmospheric Whistlers exhibited, quite evocatively, alongside some of the artist’s furniture and other belongings.

The nearby Charles Rennie Mackintosh house is also administered by the Hunterian. The home of Glasgow’s most famous architect was disassembled, moved and reassembled in its current location when the land at its former site threatened to subside. Today it is once again a jewel box of a home, almost too beautiful for mere mortals to inhabit.

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img3" align="alignleft" width="409"]

©YADID LEVY/ALAMY

Mackintosh’s influence is felt throughout most of Glasgow, from the breathtaking Glasgow School of Art to the Queen’s Cross Church and his Willow Tearooms on Sauchiehall Street. The tearooms are set over a jewelry store, which is a little odd, but they are exquisite.

Eight years ago, another Mackintosh building, the former headquarters of the Glasgow Herald, became The Lighthouse, Scotland’s Centre for Architecture, Design and the City. This institution celebrates the innovations in design and architecture that have supported industrial growth in Glasgow since the early 1800s and that are flowering here again.

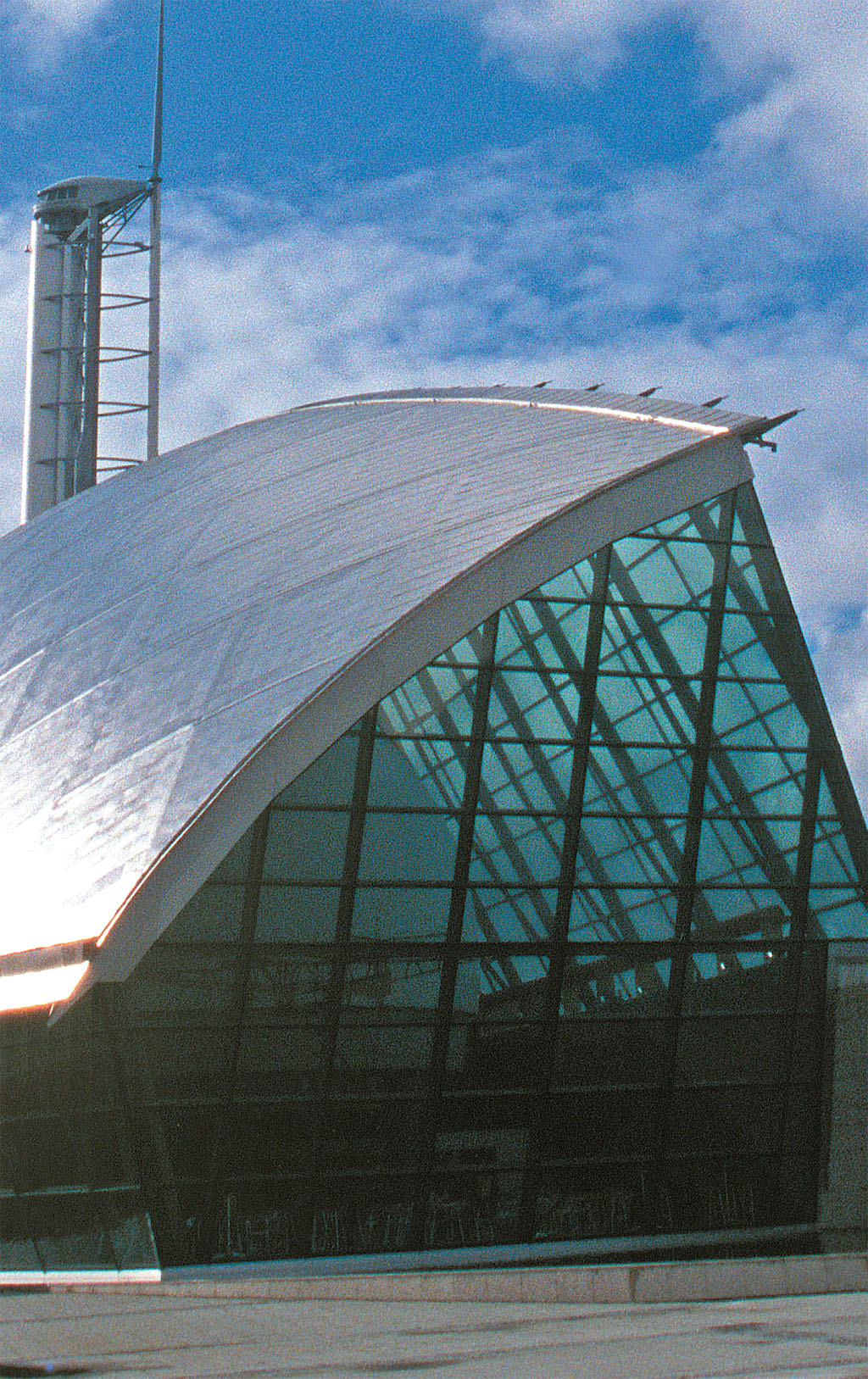

Of course, scientific advances are also necessary to industrial vitality, and Glasgow has produced its share of important researchers. Perhaps the Glasgow Science Centre will inspire another generation of them. This recently opened complex is geared to the young, with a planetarium, IMAX theater and changing displays and presentations on natural phenomena.

South of the Science Centre, almost outside the city’s limits, is the Pollok Country Park, a lovely, 360-acre estate that includes the Pollok House, the Burrell Collection and a rather friendly herd of Highland cattle. Now a National Trust property, the Pollok House was built in 1752 with subsequent additions. It is just the kind of gracious country home that I—probably like most British Heritage readers—feel nature intended me to inhabit. In summer its formal gardens are dazzling kaleidoscopes of color. We had lunch in the Edwardian kitchen, which is a history lesson in itself. The wait staff was dressed formally, I think in something close to period outfits. The food was as tasty and elegant as you could find anywhere.

Although the house features paintings by William Blake, El Greco and Goya, as well as antique silverware, glass, porcelain and furniture, the Pollok’s holdings are dwarfed by those of the nearby Burrell Collection. Sir William Burrell was a shipping magnate with a love of art that ranged from medieval to Islamic, from European masters to treasures from Egypt, China, Greece and Rome. In 1983 an award-winning building was erected to house his 8,000-piece collection, which he willed to the people of Glasgow.

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img4" align="aligncenter" width="992"]

WWW.BRITAINONVIEW.COM

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img5" align="alignleft" width="321"]

WEIDER HISTORY GROUP ARCHIVE

Ididn’t have enough time to see everything I wanted to at the Burrell Collection… or just about anywhere else in Glasgow. I didn’t visit the east side of the city to see its medieval remains, the Glasgow Cathedral and Provand’s Lordship, nor did I shop at the weekend market called the Barras or sample that well-known Glaswegian delicacy, the deep-fried Mars Bar.

I did go to the glittering Theatre Royal Glasgow, which was showing an engrossing play on its way to London. (Tickets seem to be easy to come by here, and they are less expensive than on the West End.) But I didn’t visit any of the city’s beloved sporting venues.

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

WWW.BRITAINONVIEW.COM

Although Glasgow has more attractions than you could see in a fortnight, please do not think it is touristy. Instead, it is a friendly, bustling place where visitors slip unobserved into the life of the street. Scotland’s largest city is home to three universities, and young people are everywhere.

Trade and industry no longer drive its economy, which is increasingly based on financial and business services, biotechnology, healthcare and tourism. Still, Glasgow’s character remains true to the energetic and optimistic age that shaped it. Like a scrappy second son who must make his way in the world, this spirited city seems to be looking always for its next opportunity to get ahead.

As to conversations with people, I had them with the usual people tourists encounter—friendly cab drivers, hoteliers, clerks and engaging waiters. Everyone seemed to have the time and inclination to talk. Glasgow doesn’t seem to be as fast-paced as, say, London, and people—at least those in the tourist trade—seem to like to take the time to make a joke or draw you out. The Glaswegians I met were a very humorous lot.

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©URBANMYTH/ALAMY

[caption id="AletterfromGlasgow_img8" align="alignleft" width="588"]

WWW.BRITAINONVIEW.COM

As for what I felt in Glasgow, it is hard to write about. The city is like a handsome boxer who has taken a nearly fatal punch and has struggled to his feet. The wonder is that it looks as good as it does.

In the center of the town, things are improving; new attractions are constantly being opened; upscale shops and restaurants can be seen. Yet everything has a bootstrap feel that made me a little uneasy. Will the easy-going optimism and sense of boundless energy last, I wonder? Although Glasgow didn’t charm me, I want to cheer for the city—and come back to see more of its museums.

Comments