25th August 1875: Captain Webb Swims the English Channel

BRITANNIA GLORIES IN HER SON!

HE GREATER GLORY GIVETH!

AND MATTHEW WEBB’S BRAVE NAME SHALL LIVE

As LONG AS ENGLAND LIVETH.

—from the poem “Captain Webb,” 1875

ARGUABLY, AT LEAST, THE FEAT OF swimming the English Channel, while undeniably an accomplishment of great distinction, has never earned those who achieved it quite the admiration from non-swimmers that those who have conquered Everest have enjoyed from non-climbers. Yet the parallels are strong.

Both feats were once dismissed as beyond the limits of human ability. Both Everest and the Channel defeated the most accomplished adventurers of their day: George Leigh-Mallory died on the slopes of the world’s highest peak, and in 1872 J.B. Johnson, “Champion Swimmer of England,” announced with great fanfare his plan to swim the Channel. Johnson survived, but had to be pulled from the Channel, shivering and exhausted after only about an hour and 20 minutes in the water. A “spin doctor” ahead of his time, Johnson dismissed his failure, saying that he had never really intended to swim the entire distance; it was all just a publicity stunt.

But both Everest and the Channel ultimately yielded to the efforts of their challengers—Everest to Sir Edmund Hillary, and the Channel to the less-often-remembered Matthew Webb. In the late 19th century, though, Webb was anything but unknown, and his feat, all too briefly, earned him acclaim similar to that achieved by Hillary more than three-quarters of a century later.

[caption id="ALongDistanceSwimmerBecomesaNationalHeroBriefly_img1" align="aligncenter" width="782"]

HULTON ARCHME

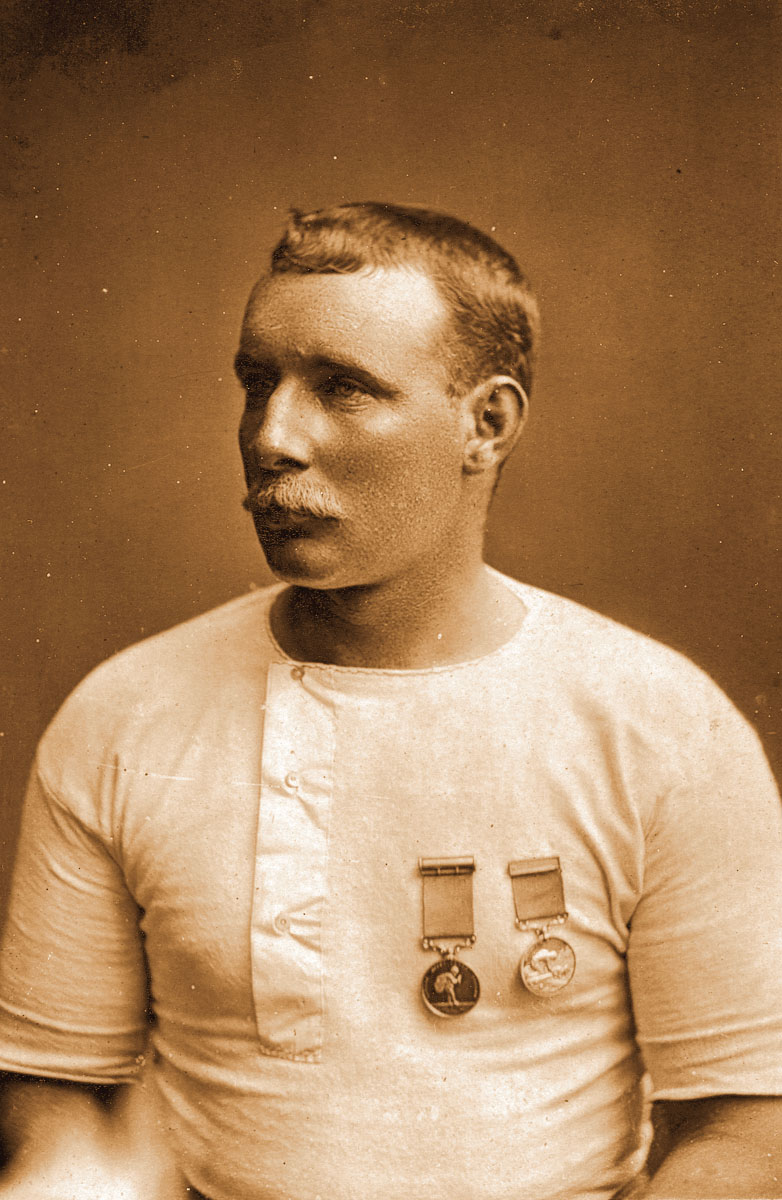

Ironically, J.B. Johnson’s “publicity stunt” set the stage for the first successful crossing, because the hubbub surrounding his attempt reached the ears of Captain Webb, a bold merchant seaman who had recently earned two medals for diving into the Atlantic in a failed effort to save a drowning man. Webb became enamoured of the thought of giving the Channel a try himself. He hardly looked the part, and when he approached Robert Watson, a renowned organizer of swimming competitions, with news of his intentions, Watson politely brushed him off. Neither Webb’s physique nor his stroke seemed suited to the task. He was a burly man, not really designed for slicing through the waves, and he favoured the breaststroke, which he employed to chug along at a pace that J.B. Johnson might have laughed at.

But Webb did have bucketfuls of endurance and determination. When he stubbornly returned to Watson, insisting on proving his athleticism by swimming in the Thames, Watson remembered that Webb “swam until we were tired of looking at him.” Still Webb, eager to make his point, proposed going farther, but his witnesses had had enough and conceded that, yes, Webb was indeed a capable swimmer.

Before Webb was able to make his own attempt to cross the Channel, he was momentarily upstaged by another strange publicity stunt that foreshadowed the debate among the first mountaineers to challenge Everest, over whether it was sporting for climbers to use oxygen tanks. Several months before Webb’s own departure, an American named Paul Boynton successfully crossed the Channel under his own power—but not quite by swimming. Boynton’s purpose was not to win acclaim for himself, but to promote a new invention being marketed by his sponsor. So Boynton made the crossing wearing Merriman’s Patent Waterproof Life-Saving Apparatus, an inflatable rubber suit designed to be the last word in life preservers. The Apparatus amounted to a life raft that you wore, complete with a sail that attached to the wearer’s foot, paddles like those used by modem kayakers, and waterproof compartments to hold food, drink, and even books to wile away the time. Webb made little attempt to hide his disdain for such contraptions, noting that he made his own long-distance swims without “any life-saving dress or artificial means of floating.”

THE WEATHER, SEEMINGLY INTENT ON making things difficult for Webb, frustrated and embarrassed him. Cold air and choppy waves persuaded him to postpone his departure repeatedly, until, either fearing he would become an object of ridicule or maybe just unable to contain his own impatience any longer, he finally set out in very poor conditions late on the afternoon of 12th August. As expected, the tides in the Channel swept him eastward on the first leg of a zigzag course toward the coast of France. In the face of a pelting rainstorm, he made slow progress, but the weather deteriorated even further, so that before long not only was concern growing for Webb’s safety, but also for those in the small boat that kept pace with him.

“The sea was rising every minute,” Webb later wrote, “breaking over the small boat, and threatening to swamp it. It was making a shuttlecock of poor me…but the small boat suffered more than I did and those in it finally called out to me that they could stand it no longer.” By then, Webb was inclined to agree: “The elements were too strong for me that time.”

Still, Webb had endured horrific conditions for nearly seven hours before giving in, far surpassing Johnson’s performance. Even Boynton in his LifeSaving Apparatus had failed during an early attempt in similar conditions. No one seemed inclined to crow over Webb’s failure.

A correspondent for The Daily Telegraph, watching from the nearby boat, wrote that Webb’s “pale and haggard face told of thorough exhaustion…“

Webb himself, though, couldn’t rest easy with his aborted swim and, after a short rest, determined to try again. To Webb’s certain annoyance, the weather continued to give him fits, and he again postponed his swim hoping for more suitable conditions, all the while fearing that his delays might make people think he had lost confidence in himself.

The morning of 24th August finally brought fair weather, and at precisely 12.56 pm, from his perch atop the Admiralty Pier off the coast of Dover, Webb pointed in the direction of France for the benefit of a crowd of well-wishers and plunged into the water.

This time, conditions were ideal, and Webb chugged away hour after hour at his typically slow pace of 20 strokes per minute. Mostly he used his favourite breaststroke, but also the sidestroke he had learned specifically for this historic swim. Periodically he paused for a gulp of ale or tea, and a reassuring “All right” when the crew in the boat that followed him asked how he was feeling.

At about 7.00 the sun set, and Webb swam on in near total darkness, his stroke still powerful. Then at 9.30, a jellyfish stung him on the arm. Once again, he told his supporters that he was all right, but they could tell that the pain in his arm had caused his stroke to weaken.

By 3.00 am the tide began to work against Webb, drawing him away from Cap Gris Nez, the nearest point along the French coast. As he drew within a few miles of land, the wind and waves began to rise, and Webb’s strokes became ever slower and less efficient. One of his companions in the boat jumped into the water to encourage him by swimming alongside. Others cheered him on. A correspondent for The Daily Telegraph, watching from the nearby boat, wrote that Webb’s “pale and haggard face told of thorough exhaustion; but his indomitable pluck would not allow him to give up the prize so near.”

Too tired to kick, Webb now depended entirely on a weary 12 strokes per minute to propel himself the last 200 yards. At 10.40 am on the 25th, he stumbled onto the coast of France and into the record books.

SADLY, WEBB’S 22 HOURS IN THE Channel, difficult as they were, marked the high point of his life. The adulation his feat earned him faded rapidly, and he spent the remainder of his short life in a pathetic quest to recover his former acclaim and to eke out a meagre living by performing odd aquatic stunts like spending 60 hours in an aquarium. He challenged his old nemesis Boynton to a pair of inconclusive races, Webb in his swimsuit, Boynton in his inflatable Apparatus. It’s hard to imagine exactly what even a conclusive finish to such a contest would have proven. Seemingly Webb was driven by a need for money, but also by a burning need to show he was not a one-hit wonder—a mission that became ever harder as age and failing health sapped his strength.

Finally, driven by desperation and perhaps a mind that had begun to come unstuck, he planned a stunt that, if successful, would outshine even his cross-Channel swim—he proposed to swim the Niagara River Rapids on the border between the U.S. and Canada. Despite repeated assurances that the river, with its notorious whirlpool, was impossible to swim, Webb jumped into the water in the best of spirits and didn’t emerge until a boater found his lifeless body floating in the river four days later.

The great champion of England never returned home; his body is buried in Niagara, beneath a monument that makes no mention whatsoever of his greatest accomplishment.

Comments