JOHN BUNYAN AND THE PILGRIM&rsq;S PROGRESS

[caption id="ATinkersTreasure_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©Iegge/Alamy

Bunyan’s allegory of a Christian’s journey toward the kingdom of God borrowed from ancient Christian themes, but this simple English “Everyman” successfully wove them into a narrative that has entranced readers in a way like no other.

“As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a Den, and I laid me down in that place to sleep: and, as I slept, I dreamed a dream….”

—John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress

GREAT INSIGHT, GREAT WISDOM AND GREAT ART are not entirely dependent upon a great education. Shakespeare, the greatest of all English writers, for example, is famously remembered as being an upstart who had learned “small latin and less greek” and had never studied at a university. Although the most highly polished and elegantly crafted literary creation of the 17th century—the King James Bible—had indeed been the work of Oxford and Cambridge university scholars, the second most influential Christian work of the era came from the hand of a lowly tinker whose early years were, if anything, even more humble than the Bard’s.

The tinker’s literary treasure is The Pilgrim’s Progress, described by biographer Edmund Venables as “the book which has probably passed through more editions, had a greater number of readers, and been translated into more languages than any other book in the English tongue.” The tinker was John Bunyan, a native of the rural hamlet of Elstow in Bedfordshire, whose personal struggles with faith and godliness inspired his vivid and imaginative tale of a pilgrim’s epic trek toward a distant Promised Land.

The metaphor of the Christian life as a journey did not originate with Bunyan. One of the earliest Christian symbols, still found in some British churches, was the labyrinth, whose winding pathways and dead ends symbolize the penitent’s struggle to find the true road to righteousness. The labyrinth was a simple but powerful means of teaching illiterate masses. Bunyan’s genius lay in expanding the metaphor into a full-blown narrative with the power to engage the imagination of readers at a time when illiteracy was no longer so universal. To this end his lack of higher learning served a useful purpose, because throughout his life, Bunyan remained a man of the common people, able to communicate profound ideas in plain yet vivid language. Indeed, while many schoolchildren today struggle with Shakespeare’s lofty style, Bunyan’s is, by comparison, matter-of-fact and accessible.

While Bunyan drew inspiration from existing spiritual metaphors, his masterpiece was, first and foremost, a product of his own experience and his own painful struggles with the concept of holiness. Bunyan sincerely considered himself to be, in the years prior to his literary successes, a complete reprobate. He titled his short autobiography Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, a self-appraisal that he undoubtedly meant in the most literal terms. The story of his life from his childhood through his years of imprisonment is painful to read, racked as it is with overly harsh self-criticism and fatalistic pessimism. But it gives readers an entrée into the mind of the character named Christian in Bunyan’s much more famous work. The Christian of The Pilgrim’s Progress is, of course, meant to represent everyone who seeks a holy life, but most of all, Christian is John Bunyan.

Bunyan’s own story begins in Elstow, where he led what would surely seem to dispassionate 21st-century observers to be an unremarkable childhood, filled with the typical childhood amusements. Bunyan, though, lived in a different age, governed by different mores. Activities that we accept as simple, honest pleasures were then sometimes deemed to be vices. Still, even given the more puritanical standards of his day, Bunyan was remarkably self-critical. He condemned himself in the harshest terms for engaging in such innocent and mundane activities as sport and dancing, and found to his own despair that he would rather enjoy these pastimes than repent of them. This realization drove him even deeper into self-loathing. Despair over the failure to live a model life echoes throughout the pages of The Pilgrim’s Progress, and provides the impetus for the hero’s quest: “As he read, he wept, and trembled; and, not being able longer to contain, he brake out with a lamentable cry, saying, What shall I do?”

[caption id="ATinkersTreasure_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©Eric Crichton/Corbis

BUNYAN

[caption id="ATinkersTreasure_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

The Granger Collection, NY

In truth, his many biographers agree that Bunyan seems to have been no more ill-mannered or devilish than any other youngster, with perhaps one exception. He wrote that he had “few equals both for cursing, swearing, lying and blaspheming the holy name of God,” and in this case, at least, we have reason to believe him.

“As I was standing at a neighbor’s shop-window,” he records in his autobiography, “and there cursing and swearing, and playing the madman, after my wonted manner, there sat within, the woman of the house, and heard me; who though she was a very loose and ungodly wretch, yet protested that I swore and cursed at that most fearful rate, that she was made to tremble to hear me; and told me further, that I was the ungodliest fellow for swearing that she ever heard in all her life; and that I, by thus doing, was able to spoil all the youth in the whole town, if they but came in my company.”

Such words, coming from a neighbor of no great virtue herself, spurred him to an effort at repentance. On the whole, however, the often well-meant advice and teaching of Bunyan’s Bedfordshire neighbors did more harm than good. Having chosen to strive for holiness, the brutally self-critical Bunyan continued to despise himself for every fault. When he confided in a respected neighbor that he feared that he had committed the “unpardonable sin” mentioned in the gospel of Mark, his counselor unhelpfully replied that, yes, he probably had. Bunyan’s despair reached new depths.

Bunyan’s torturous journey toward the kind of faith that brings comfort rather than self-condemnation was epic. Bunyan’s own account of it in his autobiography—dozens of pages filled with outpourings of grief and agony—is interrupted by only the briefest occasional hints of hope.

Like Bunyan, the early part of Christian’s journey leads him into and through many perils and temptations, vividly embodied by the writer in such characters as Evangelist, Obstinate and Pliable, and such locations as the City of Destruction and the Slough of Despond. Tellingly though, and perhaps unexpected to many of its readers, Christian’s literary pilgrimage does not end in the character’s conversion to Christianity. That part of the journey, in fact, occurs relatively early in the narrative, when Bunyan’s pilgrim has a dramatic encounter:

He ran thus till he came at a place somewhat ascending, and upon that place stood a cross, and a little below, in the bottom, a sepulchre. So I saw in my dream, that just as Christian came up with the cross, his burden loosed from off his shoulders, and fell from off his back….Then was Christian glad and lightsome, and said, with a merry heart, “He hath given me rest by his sorrow, and life by his death.”

The placement of this pivotal event in the first third of his tale testifies to the author’s understanding of the Christian concept of “sanctification,” the idea that once a pilgrim accepts the teachings of Christ, his journey continues, but the goal then changes from a search for truth to the challenge of leading a life that is, indeed, Christ-like.

For Bunyan, the turning point on his personal narrow path was perplexingly simple: “One day,” he described, “this sentence fell upon my soul, ‘Thy righteousness is in heaven….’ I saw, moreover, that it was not my good frame of heart that made my righteousness better, nor yet my bad frame that made my righteousness worse….Now did my chains fall off my legs indeed, I was loosed from my afflictions.” One might have expected that the years of self-loathing and despair that had plagued Bunyan would have required stronger medicine, but nonetheless, this simple thought that popped unexpectedly into his mind provided the necessary comfort and allowed him to leave all his anguish behind him.

[caption id="ATinkersTreasure_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© Eric Crichton/Corbis

‘THEN WAN CHRISTIAN GLAD AND LIGHTSOME AND SAID, WITH A MERRY HEART, “HE HATH GIVE ME REST BY HIS SORROW, AND LIFE BY HIS DEATH.”’

AMERICA WAS NOT JUST THE NEW WORLD, BUT THE GOAL OF CHRISTIAN’S QUEST.

That is not to say, though, that his troubles were over. As his fictional hero Christian would discover, the road to sanctification is rife with peril even for the self-confident, and in 17th-century Bedfordshire this danger was all the more potent. It was a time of conflict between the Anglican Church and the Nonconformists, or Puritans. Puritanism, in the eyes of Anglicans in the recently restored monarchy, represented a holdover from the Commonwealth under the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, and thus a potential threat to political and religious progress. As a result, Nonconformist worship was regulated under a series of restrictive laws that forbade all religious gatherings that did not adhere strictly to the forms of the Anglican Church.

By the time these laws were enacted, Bunyan, now having joined a local Baptist congregation, believed that he had received a calling to preach. He noted that his Bedford neighbors “did perceive that God had counted me worthy to understand something of his will in his holy and blessed word, and had given me utterance, in some measure, to express what I saw.”

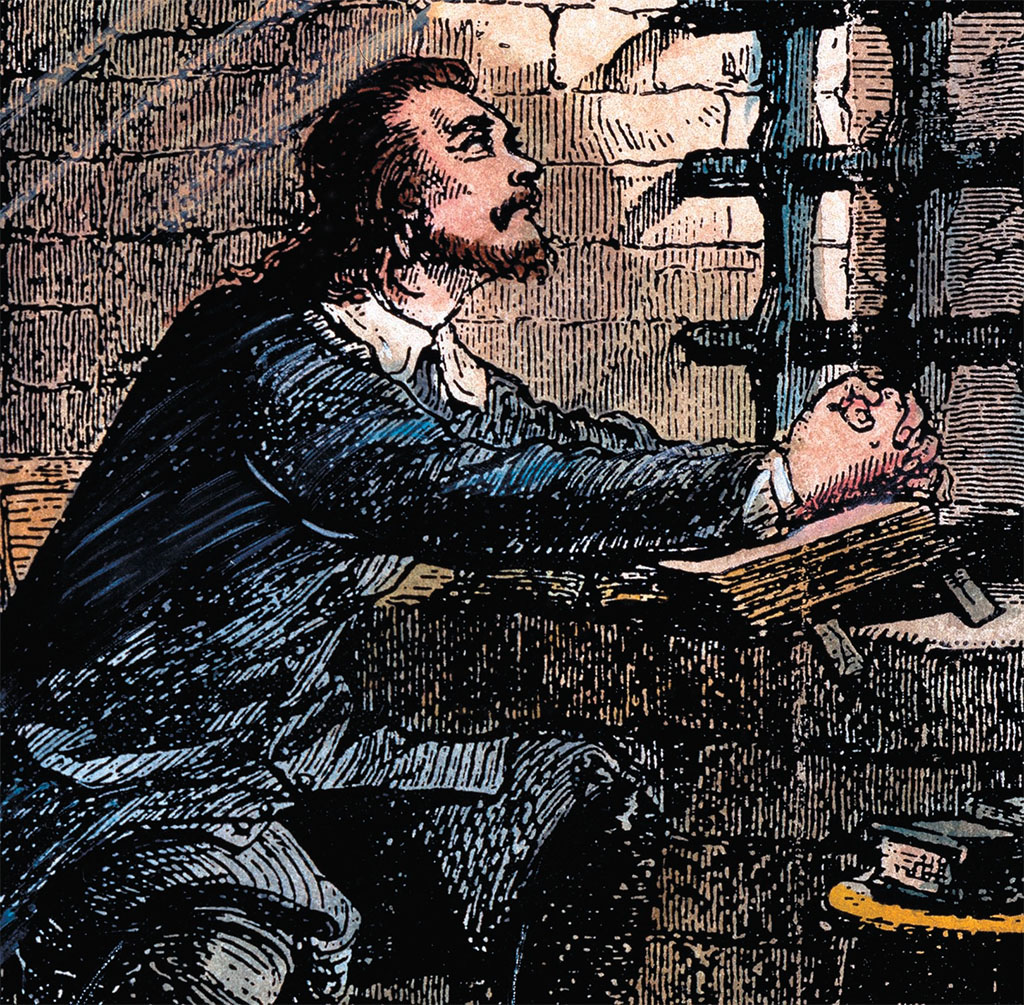

In November 1660, Bunyan’s personal journey was apparently detoured by the inevitable: “Having made profession of the glorious gospel of Christ a long time, and preached the same about five years, I was apprehended at a meeting of good people in the country…and had me before a justice….I was indicted for an upholder and maintainer of unlawful assemblies and for not conforming to the national worship of the church of England….So, being delivered up to the gaoler’s hands, I was had home to prison, and there have lain now complete for twelve years.”

[caption id="ATinkersTreasure_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Bunyan’s autobiography, written during his long imprisonment, concludes abruptly soon after this description of his arrest, leaving readers no hint that a much greater and influential work was also taking shape in the confines of his cell. In fact, he completed portions of at least nine books during his confinement. Ironically, the 12 years from 1660 to 1672, during which his physical freedom was curtailed by prison, comprised the greatest spiritual journey of his life. Whereas he had once been prey to fears and temptations, he now considered his incarceration itself to be a ministry, and his own perseverance under trial to be an example for others to follow. He might well have avoided much of his punishment by simply agreeing to give up preaching, but he refused, saying, “If you let me out today, I will preach tomorrow.” By submitting himself to imprisonment, Bunyan was freed from all distractions and therefore perfectly placed to write the greatest testimony of his age, and one of the most remarkable of all time.

[caption id="ATinkersTreasure_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

The Granger Collection, NY

The Pilgrim’s Progress was, in its own way, as nonconformist as Bunyan. In our modern times, the use of allegory as a means of conveying a spiritual message doesn’t raise eyebrows, but in the puritanical world in which Bunyan moved, such an approach was potentially more than just unorthodox. Using fiction to proclaim Christian truths was deemed improper, if not blasphemous. Recognizing that some might think he was treading on unholy ground by indulging in allegory, Bunyan felt compelled to begin his book with an apology in verse:

Well, when I had thus put mine ends together,

I shewed them others, that I might see whether

They would condemn them, or them justify:

And some said, Let them live; some, Let them die;

Some said, JOHN, print it; others said, Not so;

Some said, It might do good; others said, No.

Despite these misgivings, Bunyan’s allegory met with almost immediate popular acceptance, going through eight editions during the first decade of its publication.

The Pilgrim’s Progress resonated in a special way for the settlers who carried it with them to North America, where it has remained as admired as in the land of its author. To the colonists, many of them Puritans themselves, America was not just the New World, but a better one—the embodiment of the promised New Jerusalem, the goal of Christian’s quest. American settlers—not only those in Massachusetts’ Plimouth Plantation—were therefore Pilgrims not only in name, but in spirit. More than readers firmly rooted in England, the colonists could identify with the hero of this story, because they too had gone in search of a better place.

In a real sense, the Americans’ understanding of themselves as traveling a Pilgrimesque path toward a divinely shaped future was picked up and used as a theme by later generations of American writers. It appears most notably, perhaps, in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in which the journey of discovery takes to the waters of the Mississippi River.

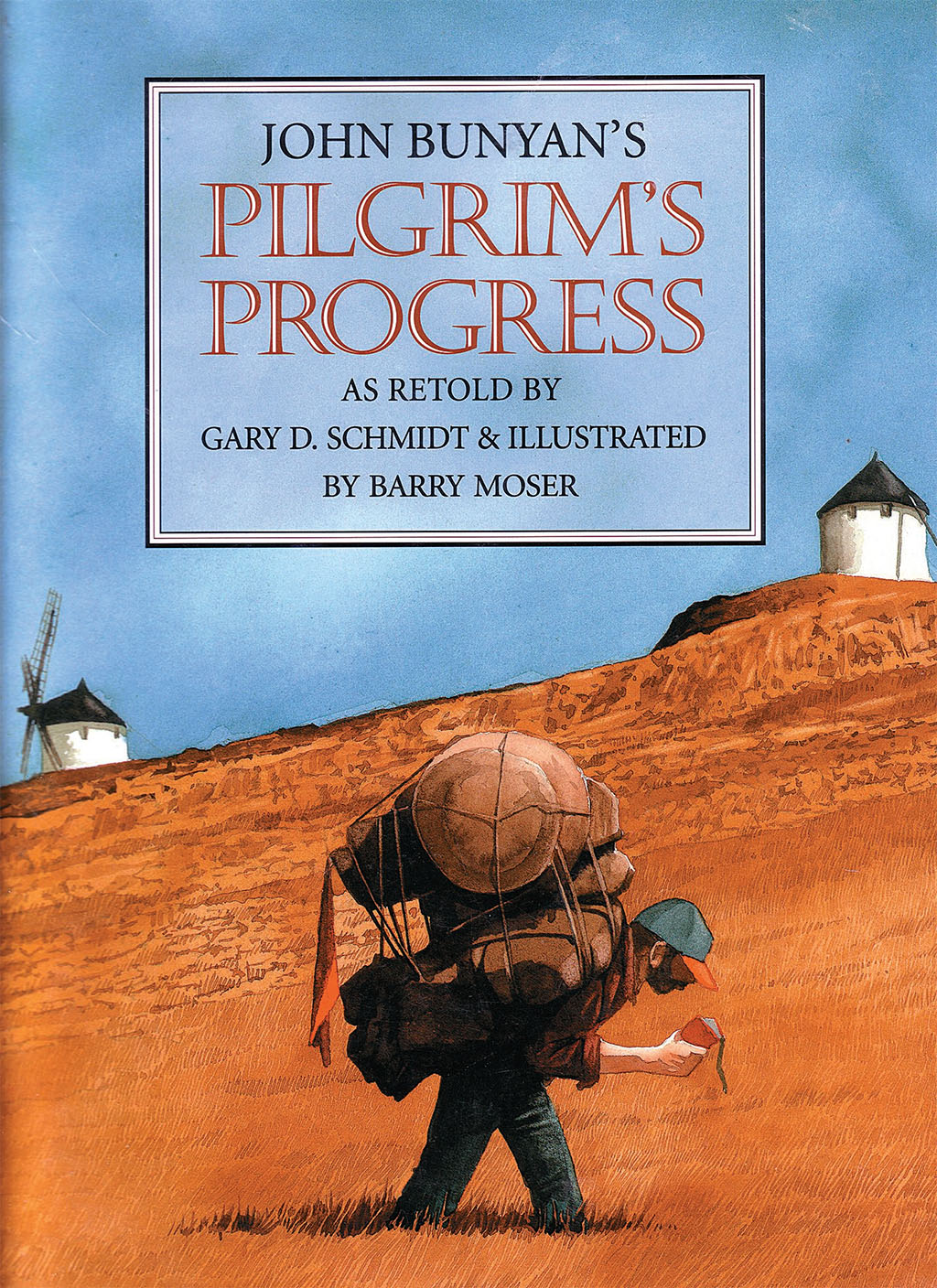

Generations and countless editions further along, The Pilgrim’s Progress remains a widely read classic, and not just among the latest crop of spiritual seekers. It is a stirring adventure tale that engages the imaginations of readers of many descriptions, including children. Many wonderfully illustrated editions produced during the 20th century catered to youngsters, who enjoyed the story without ever comprehending the deeper spiritual meaning behind Christian’s rousing exploits. Many of these are wonderfully collectible by fans of the book.

Critics and devotees alike might strain to find an explanation for why this story from an uneducated tinker’s imagination should prove such an enduring tale, appealing equally to philosophers and children. Yet for the simplest and most sensible explanation, the reader needs look no further than Bunyan’s own introductory Apology, where he aptly observes:

This book is writ in such a dialect

As may the minds of listless men affect:

It seems a novelty, and yet contains

Nothing but sound and honest gospel strains.

The Pilgrim’s Progress remains a timeless classic because it rings with a timeless theme.

Comments