“A journey into Sir Walter Scott’s imagination.” That is how Jason Dyer, chief executive of the Abbotsford Trust, describes a visit to Scott’s home near Melrose in the Scottish Borders. Scott himself described Abbotsford as “Conundrum Castle” and it has rather unfairly been described as his “finest historical novel.”

Walter Scott was the son of a successful lawyer and he followed his father into the legal profession. He was appointed Sheriff, (a judge in the lower courts of the Scottish Legal system) of Selkirkshire in 1799 and became Principal Clerk at the Court of Session (Scotland’s High Court) in Edinburgh in 1806. While these positions would have allowed Scott to live comfortably, his real income came from writing.

Abbotsford, which was to be his dream home, had more humble origins. Scott initially purchased a small farmhouse and 110 acres close to the River Tweed in 1811. He intended the property, known locally as “Clarty (Dirty) Hole,” to reflect his romantic nature, and, aware that there had been both a monastery and ford nearby, renamed it Abbotsford. He purchased more land and the building underwent three development phases from 1817 to the 1850s to make a neobaronial mansion house.

Abbotsford has recently re-opened following a £12-million refurbishment and now appears to visitors as it would have when Scott himself was in residence. The grand baronial entrance hall still displays examples of Scott’s collection of antiquarian relics and heraldic shields.

The grate in the fireplace was said to have belonged to Archbishop Sharp, who was murdered by Covenanters in May 1679. Scott often drew inspiration from his collection, and his novel Old Mortality, written in 1816, opens the day after that killing. Oak paneling on the walls came from Dunfermline Abbey, and one of the skulls on the mantelpiece is believed to have been cast from the skull of Robert the Bruce. On either side of the door to Scott’s study are two complete suits of armor, the larger of the two thought to have belonged to Sir John Cheney, who fought at the Battle of Bosworth Field, scene of the death of Richard III.

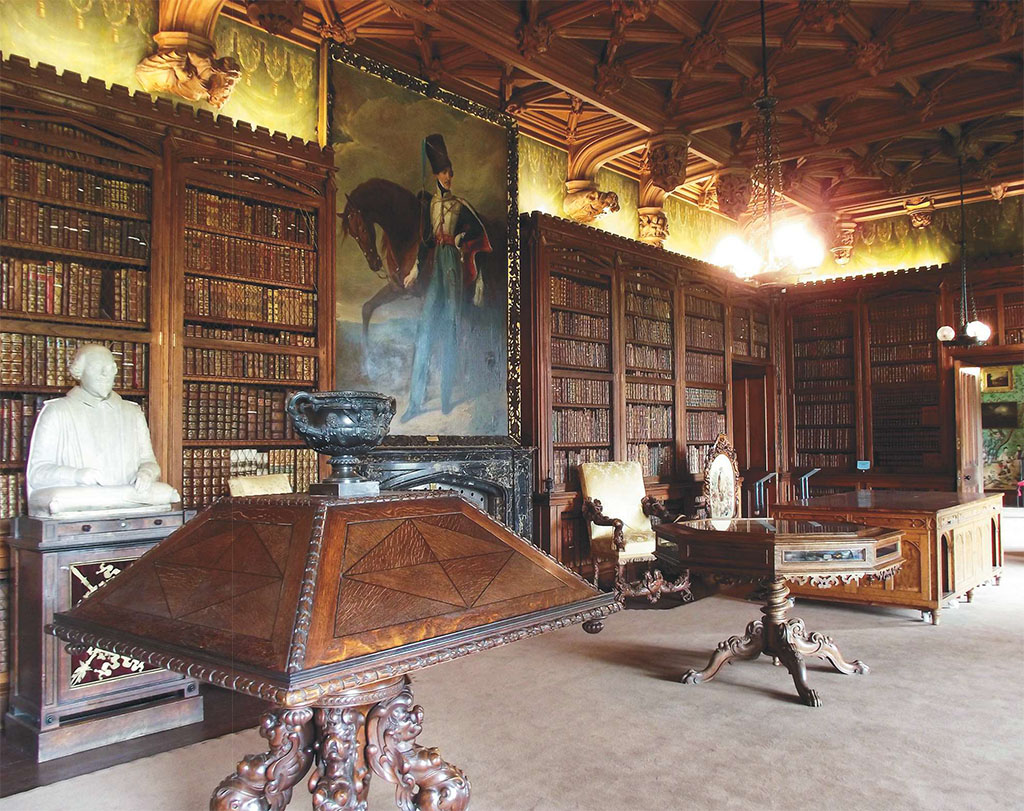

Scott’s library contains some 7,000 books, and each is in the exact spot where he originally filed it. “The hottest books, the volumes Scott referred to oftenest,” Dyer says, “are those closest to the fireplace.” Above the library shelves are painted representations of green draperies, while the ornate woodwork on the ceiling, reminiscent of work found in Melrose Abbey and Rosslyn Chapel, is painted to blend with the Jamaican cedar of the bookcases.

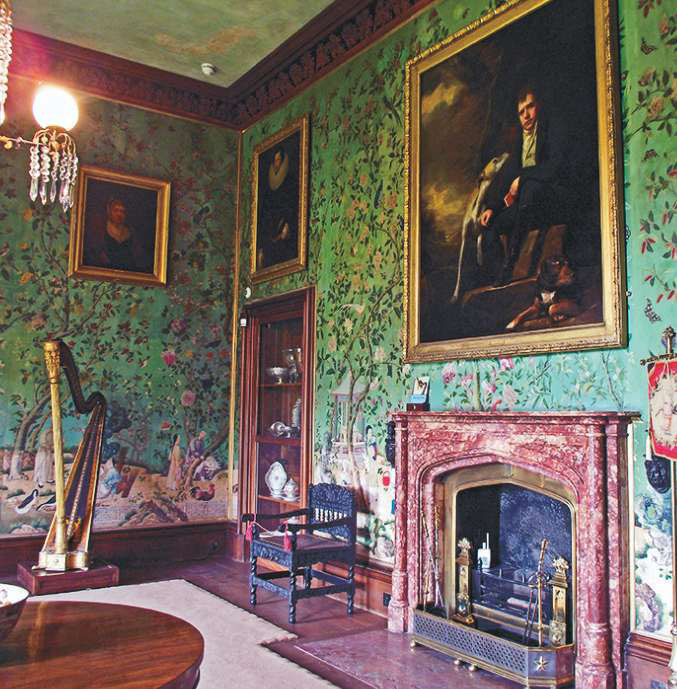

The drawing room is where visitors were entertained or, if there were no guests, the family gathered to spend the evening in the pursuits of the time: reading and needlework for the ladies, conversation and sometimes musical entertainment. The wall paper in the drawing room was hand-painted in China and the painting of Scott above the fireplace is by Sir Henry Raeburn, the leading Scottish portrait painter of the age.

Despite his enthusiasm for historical relics, Scott was also a progressive man, and Abbotsford was one of the first properties in Scotland to be lit by gas. Another innovation is the air-bells at either side of the fireplace. By pressing the plunger, compressed air traveled through a tube to the basement where it rang a bell to summon one of the servants.

[caption id="AbbotsfordRevisited_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PAYING A VISIT TO ABBOTSFORD

Abbotsford, including the new visitor center, is open between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m. For further information see www.scottsabbotsford.co.uk.

The property lies two miles from Melrose in the Scottish Borders. From Edinburgh, travel south on the A1, follow the signs for Berwick-upon-Tweed before joining the A720 and then the A68 for Jedburgh and then Melrose. From Melrose, follow the clear signs to Abbotsford. The journey, approximately 40 miles, takes around an hour by car. Buses also run from Edinburgh to Melrose, but there is no train service.

The armory was originally intended to be a room for Lady Scott, but Scott was persuaded to use it to show off his fine collection of arms and armor. Whether this display inspired Scott or not—his vast collection includes Rob Roy’s dirk, pistol and sporran and the sword of the great Montrose—the writer used it as his private sitting room.

More peacefully, the dining room is where Scott hosted dinner for his many guests, although privately he often lamented that their presence kept him from writing. Nevertheless, he was a warm and hospitable host, and the dining room was the scene of much jollity during his lifetime. Sadly, Scott died there in a bed made up for him at the window, where he could see his beloved River Tweed.

To reach the ante room, visitors pass down the “religious corridor,” just as the Scott family would have done when they retired for the night. Scott intended that the religious corridor, as the name suggests, should give the feel of a place of worship. The ante room itself contains painting and drawings of family, friends and his favorite dogs. Other drawings illustrate tales Scott would tell his guests; the room includes a maquette of Morris, one of the characters from Scott’s Rob Roy, shown pleading for forgiveness from Rob’s wife after having betrayed her husband to the authorities. The actual statue is in the garden, placed there after Scott’s death.

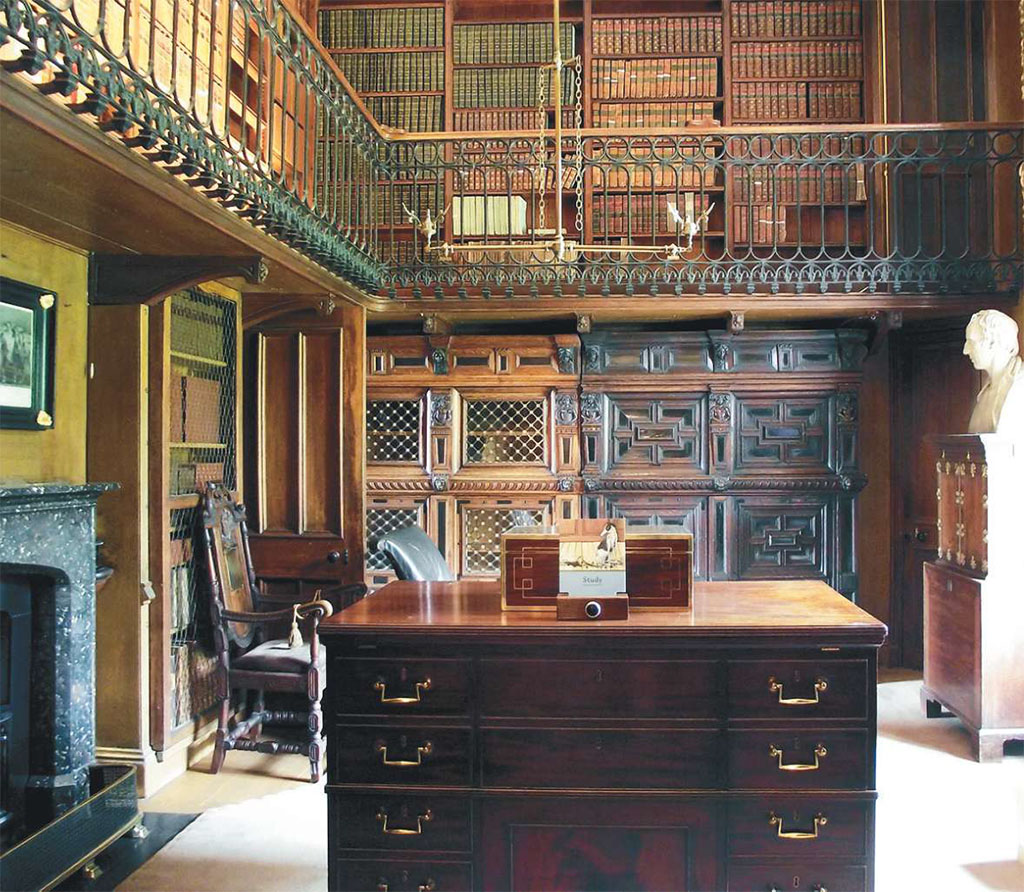

Scott’s study, completed in 1824, is perhaps the most ordinary room in the house; it was here that much of his later work was produced. For most of his career, Scott wrote for two hours before breakfast and then two hours after midday. But after 1826 his financial obligations meant that he wrote almost constantly. In the corner of the gallery is a door leading to Scott’s dressing room, which allowed him to go back and forth to his study without disturbing the rest of the household—or without visitors to the house disturbing him.

The development of Abbotsford had been largely funded by advances on Scott’s future writings. The dangers of this became obvious when his publisher, Archibald Constable, was bankrupted in 1826. Scott offered to pay off the debts of £126,000 (a vast sum for the period) by writing, provided his creditors allowed him to remain at Abbotsford rent free. He declared, “My own right hand shall pay the debt.” It says something for Scott’s reputation that the offer was accepted, and by his death he had paid off much of the outstanding debt. The remainder was cleared off when further rights to his work were sold after his death.

Sir Walter Scott was probably the first modern celebrity. In an era without the media exposure we take for granted today, that was no mean feat. In a world with few newspapers and no photography, television or electronic media, Scott was known far and wide, well beyond the boundaries of Scotland. His work was translated into more than 30 languages—and he was often referred to as The Wizard of the North.

His Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, a collection of old Scots’ ballads produced in the early 1800s, caught the public imagination, and The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805) and Marmion (1808) propelled him to fame. Scott’s series of 32 Waverley novels, penned between 1814 and 1830, were originally published anonymously, but when his identity was disclosed in 1825 his authorship had been an open secret for some time.

Scott influenced Charles Dickens, Tolstoy and other literary giants and, although his work is not as popular today, novels such as Rob Roy and Ivanhoe are still well-loved classics. He introduced a romantic vision of Scotland and its history, and left a legacy that is still important in the 21st century. Sadly, Scott’s final years were blighted by ill health, and he returned from a tour of Europe in 1832 to die at Abbotsford. He is buried in the ruins of Dryburgh Abbey.

[caption id="AbbotsfordRevisited_img6" align="alignright" width="1024"]

Sir Walter Scott’s Lair in the Borders

Comments