letters and miscellany

[caption id="AroundOurScepteredIsle_img1" align="aligncenter" width="689"]

WWW.BRITAINONVIEW.COM

THE GLORIES OF FISHBOURNE

J. Brandt of Fareham, Hants, writes: “I was interested in your article on Roman mosaics. I was surprised you didn’t mention Fishbourne Roman Palace near Chichester, West Sussex. I remember when it was discovered, when drains were to be laid across a field. Now it is covered and very interesting with many different mosaic floors.” There are, in fact, many sites with Roman mosaics in Britain. The remains of the Roman villa, especially the mosaic floors at Fishbourne, are indeed one of the grand visible remnants of Roman Britain.

THE RUFUS STONE

It really is a metal plinth, but they say the original stone is encased beneath. Located in an accessible and signposted northern corner of the New Forest, the Rufus Stone marks the place where King William II was shot and killed by an arrow during a hunting venture in 1100. Son of William the Conqueror, the unfortunate king was called William Rufus by virtue of his red beard and complexion. It remains an open question whether his death was accident or murder. One Sir Walter Tyrrel, his hunting companion, is implicated, but Rufus was such a cruel and ornery fellow that motives were all about and legion. People visit the Rufus Stone not for its intrinsic worth, though the forest glade where it sits is indeed idyllic, but because there are few genuine mysteries surrounding a monarch’s death.

A ROYAL WILLIAM AND ARTHUR

There is nothing quite like Gilbert and Sullivan. The brilliant, tempestuous partnership produced 15 immortal light operas, from Trial by Jury to The Gondoliers, each the perfect marriage of Sir William Gilbert’s witty and playful lyrics to the intricate, melodious scores of Sir Arthur Sullivan. The Savoy Theatre was built for the production of their operettas and the first London theater designed for electricity. If not the Savoy, then Sadler’s Wells or the English National Opera almost always has a Gilbert and Sullivan show in production, for an energetic choice on a free evening in London.

TO THE REGIMENT!

From the 17th century to the present, the basic unit of British military organization has been the regiment. Formed of 750-1,000 men, the regiment comprises 10 companies, each led by a captain. Nominally commanded by a colonel, day-to-day affairs in the regiment are handled by the lieutenant colonel. Until the late 1800s, commissions were bought rather than earned. Hussars, Grenadiers, Light Cavalry and the Life Guards: Loyalty and lifelong identity lies with one’s regiment of service. Here’s the toast that echoes through the centuries: “To the regiment!”

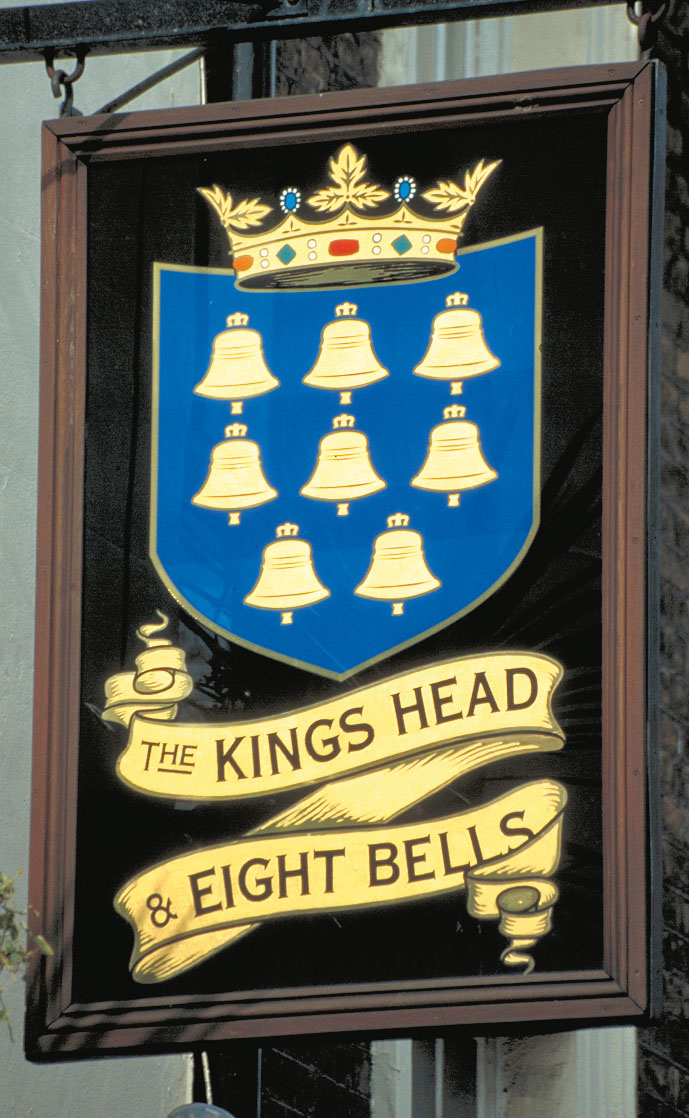

A PUB SIGN PRIMER

Back when Britain thrived under Roman occupation, a thirsty traveler could always spot a wine shop because of the bush hung out as a sign. Until fairly recently, of course, the great majority of Englishmen could not read. Through the centuries, public houses offering rest and refreshment have signified themselves by the pictorial depiction of their name on the signboard hung outside. Historic events (The Rose & Crown), occupations (The Shepherd’s Crook), famed noblemen (The Duke of Wellington) and assorted fauna (The Speckled Trout) all provide common pub names. Sources of others are less easy to identify: The Slug &Lettuce or The Pig Sty. And then there’s the place where Prince Charles took his first drink, The Queen’s Arms.

A NONFICTION BRITISH PANTHEON

In our November issue, we included an unscientific polling of the 10 most British books of all time. Brian Albright of Denver, Colo., correctly notes, “Chaucer’s verse excepted, all were fiction.” Oddly enough, that is just the way it turned out. I suspect that the great novelists of our language create images that are more memorable than do the prosaic writers. Still, Albright tantalizingly continues, “I would be interested in seeing a similar list from your staff and readers consisting of nonfiction works.”

Albright himself suggests Helene Hanff’s delightful epistolary 84, Charing Cross Road and Empire by Niall Ferguson as examples. I think of Winston Churchill’s The History of the English Speaking Peoples and Bill Bryson’s popular Notes from a Small Island. Of course, both Bryson and Hanff are Americans. Does that matter?

Let’s hear from the great BH readership. Write or e-mail your suggestions for the most quintessentially British narrative nonfiction books of all time, and we will collate a list of the most popular titles to share with all.

CASTLE DROGO, DREWSTEIGNTON, DEVON

If you are expecting the drafty ruins of a Norman fortress, Castle Drogo will come as something of a shock. Sir Edward Lutyens built the castle for a young importer early in this century. To be sure, it is made of stone, with appropriately thick walls and architectural features, but I’m not convinced that it really is a castle. Central heating, 20th-century plumbing and electricity, huge windows, proper drainage and details of design would have caused a medieval master builder to scratch his head and laugh. Castle Drogo is a marvel. The views out over Dartmoor are magnificent, as are the formal gardens. The National Trust has an aboveaverage visitors center there, with an informal restaurant and broadly stocked shop. Getting to Castle Drogo is a bit of a quest (off-the-beaten-path doesn’t begin to describe it), but it is definitely a visit worth the effort.

LITTLE JOHN’S GRAVE, HATHERSAGE

Deep in the Peak District sits the unassuming market town of Hathersage on the A625 between Chatsworth and Castleton. The old parish church perches comfortably above the main thoroughfare, as it has for centuries. Tucked on one wall of the pretty churchyard lies the tomb of Robin Hood’s trusted friend and lieutenant, Little John. The grave is clearly marked, and tended to this day by the Ancient Order of Foresters. When the medieval grave was excavated in the 1700s, the thigh bone on the exhumed skeleton measured 32 inches. That would have made Little John a bit taller than 7 feet.

BRITISH ORTHOGRAPHY

You may have noticed in the last couple of British Heritage issues that we have moved from British to American spelling and usage conventions. If you miss British orthography, you are not alone. Joan Hazel Carter speaks for you when she writes: “Please, couldn’t we have British spelling in a magazine entitled British Heritage? Most of us expatriates look to your magazine to keep us in touch with our past.” We appreciate your thoughts, Ms. Carter, and I wish that we could retain British English. However, the great majority of BH readers and many writers are North American and, to be consistent, we now consult Webster’s for all spellings.

TOUCHING THE CHORDS

It is always grand to hear when BH has hit the right note with our readers. Sophia Oka of Denver, Colo., writes: “What a great issue! I especially enjoyed the article on George Borrow—what a surprise. The entire magazine was full of fascinating articles. Keep up the good work!” The pastor of Westport Methodist Church in Swanzey, N.H., Dr. Richard Sainsbury, shares: “I very much enjoyed your article on Newton and Cowper. I have been sharing hymn history with the folks at church, and this story took pride of place. Thanks for writing a scholarly article that was spiritually sensitive.” From Danvers, Mass., Barbara Piffat pens: “Our entire family from Texas to Massachusetts subscribes to British Heritage. Keep up the excellent work with this publication!” And thank you, one and all, for the encouragement.

LEST WE FORGET V-E DAY

On May 8, 1945, the guns of Europe were silenced. Though war would continue in the Pacific into the summer, the Nazi terrorism of the Continent was at an end. For six long years Great Britain had fought the war machine of fascism. For six long years the British people suffered the privations of war and the relentless bombing of their hearths and homeland. Little wonder that when peace prevailed that springtime day the streets of Britain from London to Liverpool, Plymouth to Perth, erupted in jubilant and spontaneous revelry. Now 60 years have passed since the celebration of Victory in Europe. Each year there are among us fewer and fewer folk in Britain, Canada and the States who remember those years of World War II and the joy of its ending. As Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young remind us: Teach your children well.

Comments