British Independence Goes to the People

The battle lines are being drawn. At long last the date has been set. On June 23rd the voters of the United Kingdom will have their referendum on Britain’s continued membership in the European Union.

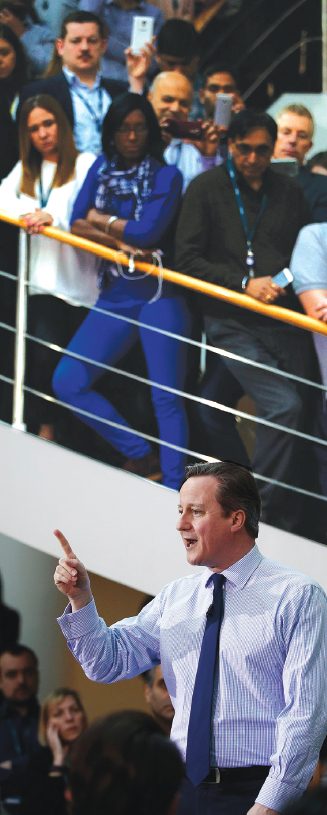

David Cameron and the Tory Party have been promising such a vote for several years. Cameron, however, opposes Britain’s exit from the EU, and he has been desperately seeking a modification of Britain’s agreement with Europe that would placate British voters sufficiently to accept continued membership.

Boris Johnson, the popular Mayor of London, Justice Minister Michael Gove and former Conservative party leader Ian Duncan Smith are among those that have lined up to support Britain’s exit–commonly referred to in the media as Brexit.

The Brexit question has split the Government and the Conservative Party. This isn’t simply a Tory issue, however. Unfettered immigration from other EU countries, mandated social benefits freely available to non-British citizens, control of borders and veto powers over Britain’s justice system are among the hottest topics in the public debate–across the British political spectrum.

Just as it is in this country, immigration is a top-of-the-leader-board issue. At present, 180,000 immigrants a year arrive legally from the Eastern European countries. Some 62 percent of British voters believe that figure is just too high and insupportable. Apart from the strain these new arrivals place on the blue collar labor force, such EU citizens are immediately entitled to the full range of British social benefits: housing, defined welfare payments and medical. David Cameron’s last ditch unsuccessful attempt to modify the terms of Britain’s participation in the EU on immigration, judicial sovereignty and other issues was ultimately rejected. Now, the question of the UK’s continued membership goes to the people.

[caption id="AtLasttheReferendum_img1" align="alignleft" width="327"]

PETER NICHOLLS/PRESS ASSOCIATIOIN

SOVEREIGNTY AND NATIONAL IDENTITY

FOR MORE THAN A GENERATION NOW, UK citizens have been encouraged to think of themselves first as Europeans rather than as British, let alone Welsh, English and Scottish. Slowly, but surely (and certainly expensively), the EU bureaucracy in Brussels has gathered to itself regulative authority with the force of law that many British citizens regard as weakening their national sovereignty.

Beyond these high profile issues, the EU sets agricultural and trade policy, stretches tentacles of regulation into every Whitehall ministry and local council, and costs the UK mightily in subsidies, mandated payments and the expense of maintaining the huge, lavish operating costs of 33,000 Euro-bureaucrats. EU rules, not local councils, even dictate how folks must dispose of their household waste.

What is at stake here is Britain’s national sovereignty. By ceding a supra-national authority to the European Parliament and the European Court of Justice, Britain surrendered its parliamentary authority back in 1975 with a referendum on what was then the Common Market. In the last 20 years, Britain has opposed 72 measures in the European Council of Ministers, each of which has been rejected.

At this point, British voters are quite evenly divided on the question. British and international businesses, as well as the important worldwide financial entities that comprise “the City” are split, as well, on their assessment of the cost-benefit analysis of British independence from Europe. The Scottish National Party is strongly pro-Europe and Scottish voters can be expected to vote heavily to remain in the EU. In England, however, the issue runs deeper than the economic and legal issues to a vein of English nationalism–not unlike the nationalism that has ignited the SNP and continuing Scottish independence movement.

In addition to the palpable internationalization of London, the English have seen their urban centers such as Birmingham, Leicester and Nottingham become increasingly “multi-cultural” and culturally less traditionally “English.” Even in a rural market town like Ross-on-Wye, at the Polish grocer’s, you can pick up a copy of the Polish-language daily paper.

NOSTALGIA ISN’T WHAT IT USED TO BE

DESPITE BRITAIN’S generous record of easy immigration to its shores from Commonwealth nations, and its broad tolerance of cultural ethnicity and religious practice, there is an understandable nostalgia for an England that many people see as having rapidly disappeared over the last generation. This nostalgic bent is nothing new; it’s a British national characteristic–one it successfully passed on to its American cousins.

As far back as Shakespeare, folks have been longing for the simpler, idyllic life of an arcadian past. It is a common motif of the great Bard’s comedies. In As You Like It, for instance, the Forest of Arden represents freedom, innocence, simplicity and living in a natural world. The city and the court, however, offer danger, sophistication, artificiality and the masks of society.

The recent final season of Downton Abbey rehearsed the theme over and again, as Lady Violet, Lord Grantham, and even the downstairs stalwarts such as Carson and Mrs. Patmore shake their head at the “modern” world and mourn the ways it has changed their lives. Viewers share their pain, because they can identify with it.

Of course, our nostalgia doesn’t simply take on a rural, pastoral character. It is also heroic in our imagination. At my local pub, Joyce has been an avid Downton Abbey fan from the beginning; we talked over and laughed about each episode this final season. Joyce is convinced that in her previous life she lived in the long gone Downton Abbey world. Naturally, in this past life, Joyce was a member of the family, not an undercook or housemaid.

The longing for this Arcadian, heroic past is the emotional fuel of the Scottish nationalism movement. The popularity of the Outlander series taps into the theme in a timely fashion. It portrays the times and passions of the Jacobite uprising in terms of heroic romance. We see attractive principals, with clean cheeks and clear, ruddy complexions, not men lying in the mud in their death throes from blade weapons, or hunted down in the woods.

At a recent dinner hosted by the Lord Mayor at Mansion House, the Bishop of London, the Rt. Rev. Richard Chartres described English identity as “terminally nostalgic.” Nostalgia is one of the cultural legacies that Americans seem to have inherited from our British forbearers. In the past, we walked further to school, in worse weather; Grandmother’s apple pies and chicken tasted better. Would we really want to turn back the years to the early 20th century, let alone to the 1800s or the Elizabethan Age? Do we long for the world of Miss Marple’s village of St. Mary Mead–or Lake Wobegon or Grovers Corners?

Downton Abbey’s finale didn’t tell the whole story. Yes, Julian Fellowes did a magnificent job of wrapping up the loose ends of all the characters’ lives. Everyone seems to have had a happy, or at least satisfying, ending. The fate of Downton Abbey itself, however, is left unresolved. We saw the beautiful mottled colors of the sunset, but not the dark to follow. When the curtain came down in 1925, we know the way of life was ending. Still to come for Downton, though, would be the Depression, and the crippling death duties to follow the inevitable passing of Lord Grantham.

For Downton, as for hundreds of ancestral estates across Britain, Tom and Lady Mary’s hands-on management and a drastic reduction of household staff would not save the estate in the long run. Like almost all the historic country estates of the nobility, long before now, Downton Abbey would be a managed tourist attraction, in the care of the National Trust, or decaying into oblivion as more than 200 mansions did in the 20th century.

If the British people vote to go it alone as a sovereign power in the contemporary world rather than to stick with the shaky European Union, they had better have a better reason than looking to the past.

SUNNY UPLANDS FOR AMERICAN TRAVEL TO BRITAIN

In the meantime, despite the doomsday predictions of the pro-Europe campaigners and the freedom and prosperity foreseen by Brexit supporters, world financial markets notoriously hate uncertainty. While the FTSE London stock market may continue to move in concert with world markets, the British pound sterling has measurably weakened against the US dollar. Presently around $1.45 to the pound, the GBP is highly unlikely to gain significantly before the June 23rd referendum at the earliest.

With the dollar the strongest that it has been in well more than a decade, this spring and summer Americans will find Great Britain to be the best travel bargain in many years. The favorable exchange rate discounts costs on hotels, food and drink, transportation and Great British goods to bring home.

To take best advantage of this likely temporary currency bargain, the strategy is to pay as much of the expense in pounds as possible, rather than in dollars. Booking on line you’ll always do better paying in pounds for hotels, airfare or tickets. Often in Britain, on credit (or debit) card purchases for goods or meals, visitors are asked whether they want to settle in dollars or pounds. Pay in pounds. And, as always, acquire GBP in cash from Cash Points (ATMs) of major banks, not from commercial exchange counters or commercial ATMs.

With this year’s 950th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings, this is the year to visit the 1066 Country of Kent and East Sussex. While you’re there, do drop in to one of the English vineyards that have been taking the wine world by storm. Or head for East Anglia and check out the Mayflower Project in Harwich. Then, follow the coast north to Norfolk, the pristine rivers of The Broads and the ancient cathedral city of Norwich. Anywhere you travel in Britain this summer, of course, there are festivals of the arts or food and drink, local fetes and eccentric rural revels that have been passed from generation to generation.

In our next issue, British Heritage Travel will unpack these and other ways to take advantage of this rare favorable exchange rate. If you have been waiting and planning to travel to Britain, now is the time. Things should be interesting.

Comments