Evesham remembers the Father of Parliament

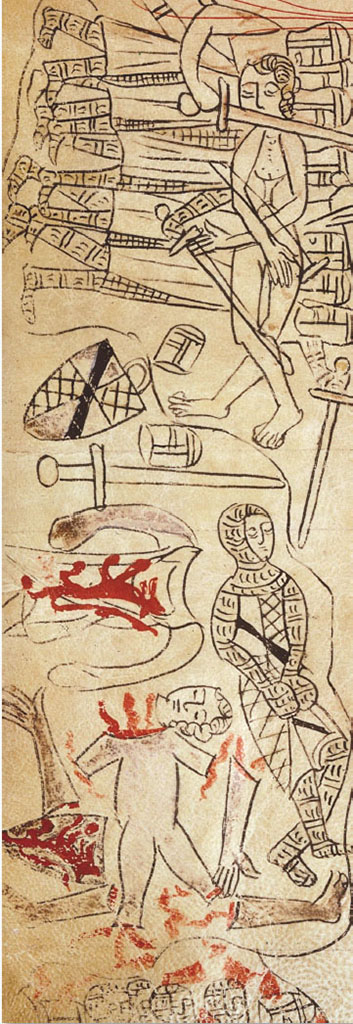

“May the Lord have mercy upon our souls, as our bodies are theirs.” So said Simon de Montfort on the morn of the Battle of Evesham. He was right, for as chronicler Robert of Gloucester conceded, this was, “the murder of Evesham, for battle it was none.”

This August, the Worcestershire market town of Evesham will celebrate the 750th anniversary of this August 4, 1265 conflict. The battle was the climactic event of the Second Barons’ War, fought between de Montfort’s rebels and King Henry III. The barons were roused by the king’s authoritarian rule—contrary to the provisions of Magna Carta. Their leader, Simon de Montfort, the 6th Earl of Leicester, called a Parliament in January 1265 that included elected burgesses from the towns and representatives of the shires. The event is considered the prototype of the House of Commons, the first step toward parliamentary democracy.

I went to school in Evesham; my grammar school lay at the foot of Greenhill where de Montfort’s barons spurred their horses into a suicidal uphill charge into the mass of a superior royal army. The anniversary was a good opportunity to go back and recreate the dramatic events.

The story begins, though, with de Montfort’s march to Evesham. I headed for Kempsey, a village crossing of the River Severn, south of Worcester. At the Battle of Lewes (May 14, 1264), a thumping victory for de Montfort, both King Henry and his heir, Prince Edward, had been taken prisoners. De Montfort, the king’s brother-in-law was England’s effective ruler, and the anointed monarch, Henry III, was his captive.

St. Mary’s Church stands high, overlooking a ford that de Montfort and his men clattered across when they arrived for battle on August 2nd. At Kempsey, de Montfort took the king into church for mass the following morning, presided over by Bishop of Worcester, Walter de Cantilupe. On the main road is a pub named in the Bishop’s honor. He chose to side with the barons, convinced that many evils were due to the Crown’s unfettered power.

Kempsey is just over four miles south of Worcester. The Malvern Hills, running north-south for eight miles, are clearly visible to the southwest. After Kempsey, de Montfort’s route isn’t precisely known, but he probably proceeded via Pershore, where the impressive abbey church survived the Dissolution.

They would have continued on a southerly route to Evesham, skirting the village of Fladbury. In the village church, the medieval stained glass was reputedly salvaged from doomed Evesham Abbey. One window depicts heraldic shields of de Montfort and his barons, all dying in the battle.

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img1" align="aligncenter" width="353"]

AKG-IMAGES/BRITISH LIBRARY

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img2" align="aligncenter" width="380"]

STEPHEN ROBERTA

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img3" align="aligncenter" width="340"]

STEPHEN ROGERS

The Baronial army headed into Evesham via its only bridge today’s Workman Bridge at Bengeworth), and bivouacked inside a loop of the Avon. There was presumably much carousing in the town that night, the army in high spirits at the prospect of reinforcements from de Montfort’s stronghold of Kenilworth to the north.

De Montfort’s first big mistake was not keeping a closer eye on Prince Edward. Under house arrest at Hereford, the prince had challenged his gullible captors to a horse race. Securing the fastest steed, Edward simply rode off and began plotting the destruction of his adversary. This was the coming of age of the young man that would become the great warrior king, Edward I.

Edward gathered his forces and headed towards Evesham from the north. Alcester, a town of Roman antiquity, hosted the prince as he marched on Evesham. There is nothing today linking the town with 1265, although the characterful old town is worth visiting, especially the Church of St. Nicholas and the town hall, rebuilt in 1641, just before another conflict between Crown and state. Alcester is eight miles west of Stratford-upon-Avon, birthplace of William Shakespeare. Henry III, however, was the monarch’s history the Bard omitted to tell.

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img4" align="aligncenter" width="390"]

NIKKI BIDGOOD/GETTY IMAGES

From Alcester, the road led south to Cleeve Prior. Here at the River Avon, Edward divided his forces. While the prince continued to Evesham, a force under Roger Mortimer forded the Avon, and secured the bridge at Bengeworth on a flanking manoeuvre.

On the morning of battle de Montfort surveyed the scene high up in Evesham Abbey, presumably believing all was well. An army approached from the north flying de Montfort banners, the relief force from Kenilworth. But it was not.

Prince Edward had caught de Montfort’s son (another Simon) off guard, with his men billeted in town, rather than in the Kenilworth fortress. The younger Simon escaped to the castle, but in the mayhem, Edward took supplies, horses, prisoners and Montfort banners.

By the time the senior de Montfort realized his error, it was too late. The approaching army was a royal one, for there were monarchical banners among those familial ones. Prince Edward’s army deployed at the top of Greenhill, spreading out between two wings of the Avon. The master had been hoodwinked by the pupil as de Montfort conceded. “They come on well; they learned that from me.”

To the southeast, Mortimer had seized the bridge, the only escape route. It was inconceivable that an experienced battle-field commander like de Montfort permitted this trap to happen, but happen it had.

The Bishop of Worcester played one final part in this drama, presiding over de Montfort’s last mass at Evesham Abbey, an event that must have been trying for both. In St. Laurence’s Church, close to the Abbey’s bell tower, stained glass depicts this scene. The glass may be from the 1950s, but it is powerful.

De Montfort went on the offensive. Drawing his force into a tight arrowhead, he charged directly at the royal line’s center. The heavens opened, with a thunderstorm greeting hostilities; de Montfort’s sympathizers would claim it was God’s verdict on the baron’s death. The fighting was bitter and lasted more than two hours. Prince Edward, thirsting for revenge, had stipulated no prisoners, and no quarter was given. The prince despatched a hand-picked squad to ensure de Montfort was identified, killed and dismembered. And so it happened.

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img5" align="aligncenter" width="290"]

STUART BLACK/ALAMY

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img6" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

NIKKI BIDGOOD/GETTY IMAGES

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img7" align="aligncenter" width="700"]

RIGHT: STEPHEN ROBERTS; BELOW: CLASSIC IMAGES/ALAMY

[caption id="BattleintheMarketGarden_img9" align="alignleft" width="189"]

The Battle of Evesham was one of the most decisive of all English battles, with the barons’ leader, 18 barons, 160 knights and some 4,000 common soldiers slaughtered. Royal casualties were slight.

At the top of Greenhill, I followed a footpath to the Leicester Tower, a folly erected in 1842 to de Montfort’s memory, where a plaque proclaims him as “the father and founder of the British House of Commons.”

From there, a walk through woods leads to the battlefield obelisk, which occupies the spot where the battle occurred. The plinth includes a representation of King Henry III, pleading for his life. The vulnerable Henry had roamed the field in a knight’s garb, but was fortunately recognized and restored. The picture shows a royal knight about to cut the king down; Henry gets his message across in the nick of time. There are excellent views of the battlefield, a landscape that is little changed over the centuries.

Crossing to the other side of Greenhill, I walked down Blayney’s Lane to Dead Men’s Ait. The name is appropriate. As the battle became a rout, de Montfort’s men fed this way hoping to get across the river to safety. Many died in the attempt and the fields leading to the Avon and the river itself must have been awash with blood.

It is hard to equate the carnage of 1265 with today’s Evesham, a quiet market town famed for market gardening, asparagus and spring blossoms. Evesham is handy for the Cotswolds, with quaint honey-coloured Cotswold-stone Broadway just eight miles south-east.

The town center is a good place to understand what happened that day 750 years ago. The Almonry Museum has a battle room, including dioramas and a battle-axe, dug up from Greenhill. In the Abbey Gardens is de Montfort’s memorial stone, unveiled in 1965, on the site of the abbey’s high altar, where the baronial leader was laid to rest. When Henry III got wind of de Montfort’s burial place, he ordered his remains reburied in less hallowed ground.

On the anniversary of the battle, the Evesham 750 festival will put Simon de Montfort back at the center of attention, with an ambitious program of events, including a battle reenactment. A man that fought a king for a cause he believed in, who called our first true Parliament and died at the point of a sword, deserves to be commemorated.

Planning A Visit

The ancient town of Alcester is strategically well placed for visiting the castle at Kenilworth, plus Kempsey, Cleeve Abbey and Fladbury as well as the town of Evesham. The Almonry Museum in Evesham is open every day (except Wednesday) March to October, and other months every day except Wednesday and Sunday.

IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD

Worcester Cathedral opens daily from 7:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. Kenilworth Castle is open daily during the summer and at weekends in winter. Warwick Castle opens daily.

THE BATTLE OF EVESHAM FESTIVAL

Evesham hosts a fortnight of events, beginning August 1, 2015 to commemorate the battle’s 750th anniversary. The Medieval Festival weekend takes place August 8 and 9, and includes the battle reeneactment.

Comments