THE NORTH OF ENGLAND OPEN AIR MUSEUM

This replica of the Pockerley Waggonway, George Stephenson’s No. 2 engine, built in 1822 and the predecessor of the Rocket, pulls passengers on short excusions. - JIM HARGAN

Double-decker trams carry visitors around Beamish’s 300-acre site - JIM HARGAN

IT MAY WELL BE the biggest open air museum in Britain—an amazing 300 acres, nearly half a square mile. Beyond doubt, Beamish (official name: Beamish, The North of England Open Air Museum) is a lot of museum to cover on foot, with six sites along a 1.5-mile loop. Fortunately, you don’t have to walk the entire distance. The single, all-inclusive admission allows you unlimited rides on an authentically restored antique tramway, with trams every 15 minutes along the loop.

And this is what Beamish is all about: the North of England in 1913, authentically re-created from one of the largest collections in the island. The double-decker trams, with their overhead electric wires, are all period antiques from northern English cities. The market town is made up of buildings moved on site from around the region, re-creating a 1913 High Street complete with pub. A coal village shows what life was like pitside, with industrial buildings and workers’ terraces from local mines. A home farm demonstrates agricultural practices of the day, using buildings that were already on the site, and a railway station displays its rolling stock. Two final sites give perspective from an earlier era. Pockerley Manor shows how a yeoman farmer would live in 1825, in a home original to the site. From it you can see something unique: an 1825 “waggonway,” a primitive early railroad, complete with reconstructed first-generation locomotives puffing along it. You can even ride in one.

Beamish, named for a nearby village, started as a local way of life was disappearing. In 1958 Frank Atkinson, a young professional curator from Yorkshire, took a major fine arts post in Durham County. At the time Durham made up the southern half of what was still a great mining region that centered on Newcastle-upon-Tyne. At-kinson soon realized that the industry that had supported the region for a quarter millennium was shutting down and would quickly disappear.

We think of industrialization as modern, but the Newcastle region had been producing coal for so long that the phrase “carrying coals to Newcastle” had its current meaning by 1661. By 1700 the Industrial Revolution was emerging in Newcastle, and by 1725 the region was dotted with large mines drained by steam engines and connected by railroads—the early prototypes of more famous versions “invented” decades later. When the Industrial Revolution was something new and wonderful in Manchester and unknown in the United States, it had been underway for a century in the Newcastle area.

By 1958, however, all this was dying rapidly. Atkinson knew that someone had to act before all traces were gone. He envisioned a museum that would “illustrate vividly the way of life of the ordinary people” at the height of the Industrial Revolution. He realized, however, that he was almost too late; nothing disappears more quickly than the ephemera of industrialization and its workers. So Atkinson established a policy of “unselective collection,” actively soliciting antique donations from the public and accepting anything of the proper age into the collection.

JIM HARGAN

BEAMISH is a dozen miles north of Durham on the A693. You can find the official Beamish Museum Web site at www.beamish.org.uk, with full information on hours and admissions. There’s a separate site for the enormous collections at the museum, www.beamishcollections.com. The Friends of Beamish organization actually predates the museum, and its members get free admission; its Web site is www.friendsofbeamish.co.uk, and provides yet more information on the Beamish collections.

By 1970 Atkinson and his group had filled a redundant army camp with the collection, and were ready to establish the museum. A unique association of eight county and borough councils provided the funding, and a site was purchased on the outer edge of Newcastle’s urban area—an old estate farm occupying a wide, rolling bowl near the village of Beamish. In 1971 the museum opened its first exhibit, and has expanded steadily since.

Beamish has been careful to describe itself as “the first open air museum in England”—a true statement as far as it goes, as existing British open air museums were all outside England, including Wales’ venerable St. Fagans with its stunning collection of folk architecture. But Beamish is no random collection of buildings. Rather, it is a highly organized presentation of a particular time and place, devoted to the way of life of ordinary workers and farmers presented with great historical accuracy and just a dash of showmanship. Its emphasis is on the daily experience of the people within the buildings, not the buildings themselves. Indeed, its concentration on working folk is so total that it has sold off the elaborate manor house that came with the property (it’s now a luxury hotel)—a total break with the old style of British history museums, based on great houses.

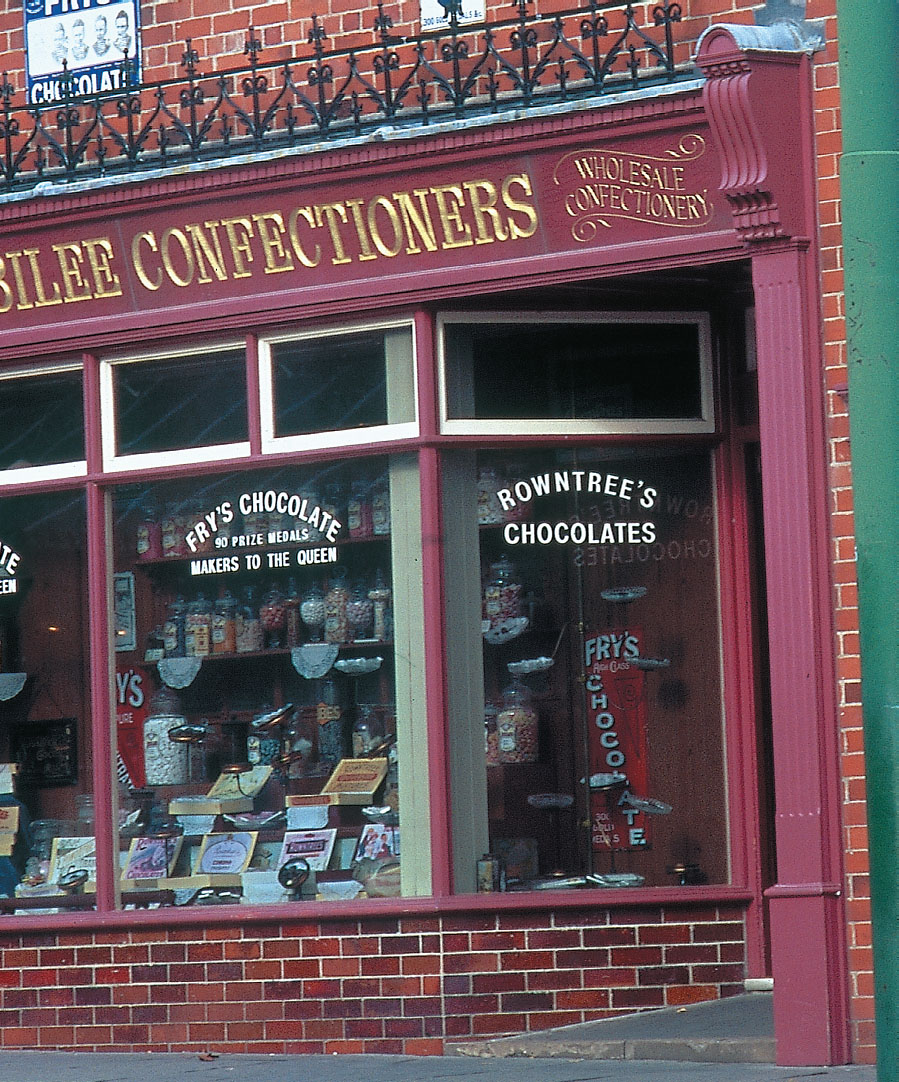

THE TOWN, located at the far end of the site, is the most elaborate and popular of the six exhibit destinations. Made up of buildings relocated from the Newcastle industrial region, it recreates, in the greatest detail, a commercial street from 1913—the year when workers’ standard of living reached its highest level to date in the industrial era. Buildings of that era include a co-op store, a bank, a Masonic temple, a tea shop, a smithy converted into a garage, stables (which house the horses employed by the museum), a candy shop, a printer and a pub. The pub sells traditionally brewed local ale from a hand pump, and packaged sandwiches. Beside the com mercial area is a range of terraces; one furnished as a lawyer’s home and office, another as a dentist’s practice. That’s a lot to see—and there are five more sites that are just as interesting. Thank goodness for the town’s pub.

At the near end of the site is the colliery, centered on an actual drift coal mine, that visitors can enter. The coal head industrial plant has an 1855 steam engine, whose working life extended for 100 years, and that is still occasionally fired up. Next door is a set of 1860s pit cottages, furnished as they would have been in 1913, complete with gardens.

Railroad enthusiasts have their own set of treats. Apart from the tram system and a set of early buses and carriages, there’s a late 19th-century railroad station with an exhibit of rolling stock, and a huge locomotive works that stores the museum’s vast collection. The most remarkable railroad site, however, is the 1820s era “waggonway,” a proto-railroad built on the bed of an actual early waggonway. Short passenger excursions feature 1820s carriage designs, pulled by authentic reproductions of locomotive engines that ran along local waggonways in 1815—that’s right, more than a decade older than the “first” locomotive, George Stephenson’s Rocket. They have a working reproduction of the Rocket as well.

For any history enthusiast, perhaps the greatest treat is standing in the flower garden of Pockerley Manor, an independent farmer’s house furnished as in 1825. From this hilltop location is a glorious view of the Durham countryside—centered on the little puffer-belly noisily belching smoke and steam along its waggonway. The farmer in 1825 would have had exactly the same view, and would have wondered what the world was coming to.

‘BEAMISH IS DEVOTED TO THE WAY OF LIFE OF ORDINARY WORKERS, PRESENTED WITH A DASH OF SHOWMANSHIP’

Across the fields lies Beamish’s original colliery village, with the coal mine’s winding engine in the bottom inset. In town, the sweet shop provided treats for a rising standard of living - JIM HARGAN

JIM HARGAN

JIM HARGAN

Comments