[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img1" align="alignleft" width="496"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img2" align="aligncenter" width="496"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img3" align="aligncenter" width="496"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img4" align="alignright" width="496"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img5" align="alignright" width="1024"]

EXTERIOR PHOTO: ©EYE35/ALAMY

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img6" align="alignleft" width="247"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img7" align="alignleft" width="678"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img8" align="aligncenter" width="678"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img9" align="alignright" width="853"]

WORKERS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM joke that the institution is like the CIA: nobody ever leaves. Why would they? It’s the United Kingdom’s number one attraction, with 8 million objects in its collection ranging from a 2 million-year-old chopping tool to African textiles created in the last decade. More than 5.5 million visitors streamed through its doors last year, but they only saw a fraction of the building and none of the hard work and planning that go into running one world’s most venerable museums.

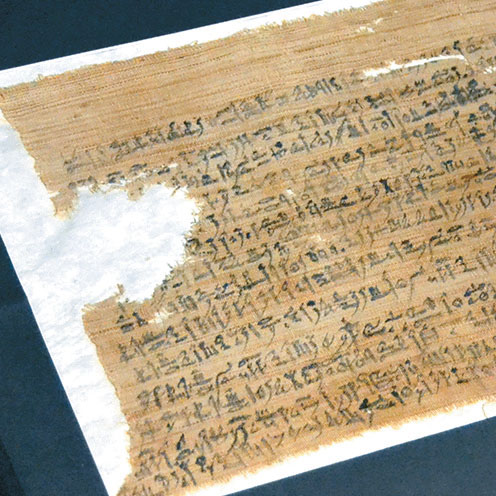

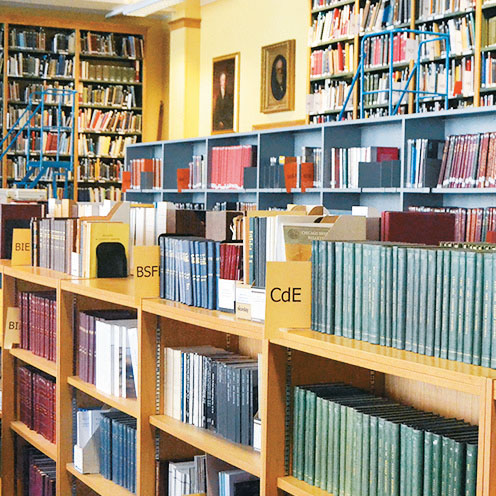

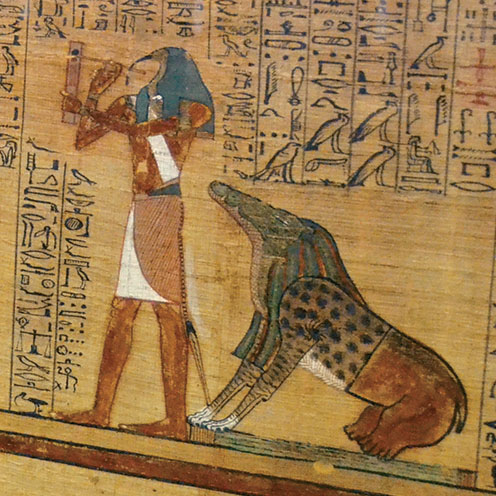

Dr. John H. Taylor is one of the elect charged with overseeing this cultural smorgasbord. As assistant keeper of the Ancient Egypt and Sudan collection, Taylor works with one of the world’s greatest Egyptology collections, and not just in terms of artifacts. Down the hall from his office there is a 22,000-volume Egyptology library, one of the largest in the world. If he wants to examine the artifacts, Taylor passes through a series of locked doors into a storage room filled with 50 mummies. Another room has hundreds of papyri preserved between sheets of glass.

Taylor’s focus in recent months has been an exhibition on mummies to open in May 2014. The exhibition will look at how modern, noninvasive procedures such as CT scans allow researchers to peer inside mummies without unwrapping them. The detailed scans map the body and its wrappings, revealing burial goods, the techniques used for mummification, and physical problems and diseases the individual suffered when alive.

An exhibition is born in a series of meetings during which each department proposes ideas. Factors such as cost, popularity and other museums’ plans are taken into account. Once a theme is settled upon, the planning starts. For this exhibition, Taylor and his colleagues made a list of mummies froma range of periods and geographic origins. They favored mummies that hadn’t already been scanned, in order to add to the museum’s vast storehouse of data. When he talked to British Heritage, Taylor had just returned from taking four mummies through the CT scan at a London hospital. An exhibition like this is a research boon to the department and spins off numerous publications.

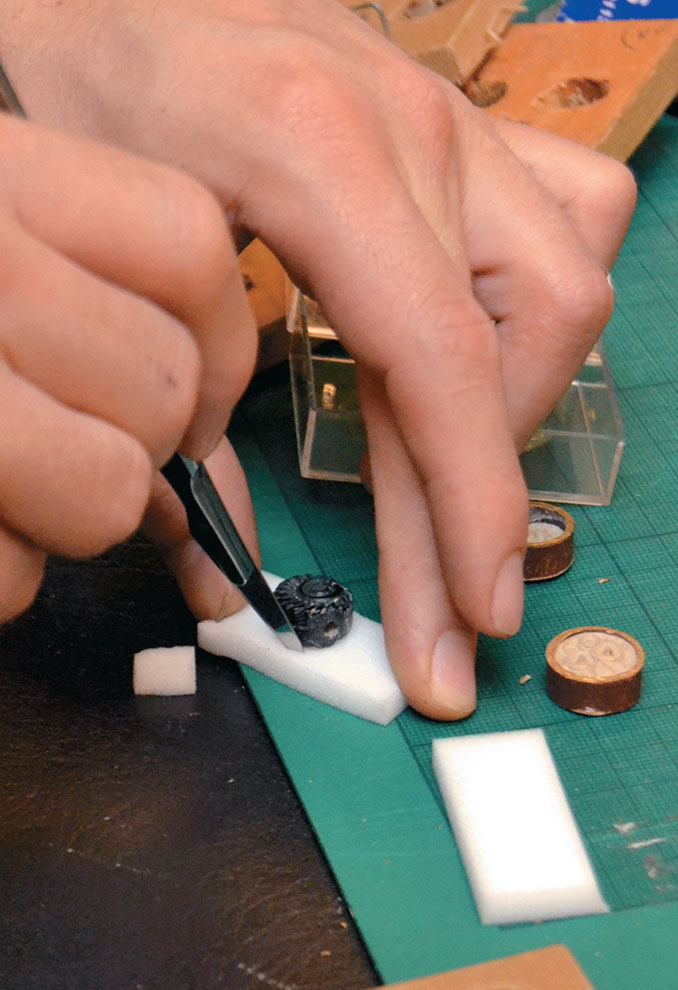

Before it can be displayed, each artifact has to be cleared by the Conservation Committee. In some cases, objects are so brittle that even the vibration of the visitors’ feet walking by the display case can cause damage. Light can also damage ancient pigments and inks.

One artifact that will probably not make it into the exhibition is a 3,000-year-old Egyptian wig made of human hair—the only one of its kind in the UK. It’s almost too delicate to be moved; it has shed a couple of its locks just sitting in the storeroom. When it was brought into the museum 100 years ago, Taylor relates with a wince, someone nailed it to a wooden stand. Now conservators are debating if it’s possible to remove the nails without damaging the wig.

“Curators have to do a range of jobs,” says Dr. Richard Hobbs, curator of the Romano-British collections. In addition to overseeing one of the museum’s more popular display areas, he’s expected to publish both academic and popular-level studies of the collections. This diversity came to the fore in 2013 when he curated an exhibition of the Mildenhall Great Dish, an elegant 4th-century Roman silver platter placed in Room 3, an exhibition space dedicated to a single object. Hobbs wanted a display that showed visitors how the dish was used, and came up with the idea of putting a replica couch around the dish and encouraging visitors to recline on it. A video display on the base around the dish showed people’s arms reaching for food. Hobbs also gave a popular gallery talk explaining the role of feasting and silverware in Roman society.

Room 3’s Objects in Focus series changes every three months and is sponsored by Asahi Shimbun, a Japanese newspaper. Hobbs said they are a “very hands-off sponsor,” making no demands as to how their money is spent. Out of gratitude, however, the museum picks a Japanese object once a year.

Studies of the crowd flow show that 1,000 daily visitors to Room 3 spend an average of three minutes there, so the displays have to be short and to the point. Text has to be concise and include illustrations related to the object.

Grabbing the public’s attention is always a concern. Dr. Andrew Shapland, curator of the Greek Bronze Age, jokes, “My gallery is on the way to the café, so I hope I get people that way.”

In a more serious vein, Shapland continues, “There is an element of serendipity. People happen upon objects and are drawn to them.” You can see this in the way people walk through the museum, first making a beeline to the objects that interest them most, then wandering almost at random, their eyes resting on various objects until one pulls them in.

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img10" align="alignleft" width="853"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img11" align="aligncenter" width="678"]

[caption id="BehindtheScenesattheBritishMuseum_img12" align="alignright" width="675"]

While there is the enduring controversy over the Elgin Marbles and a few other pieces, Shapland and Hobbs say that there have been few complaints over some of the racier Greek and Roman art. As Hobbs explains, “We always have to think about an object’s impact, but that has to be proportional to the public reaction.”

During the Pompeii exhibition in 2013, curators felt obliged to put a warning sign at the entrance to one of the rooms containing images that were shocking even in the Internet Age, but the museum didn’t receive any complaints. A Room 3 exhibition of the Warren Cup, a 1st century AD Roman silver cup showing homoerotic scenes, tallied up a grand total of one complaint.

One of Shapland’s current projects involves a group of artifacts that have been in the museum for a century. The British Salonika Force collection was gathered by soldiers stationed in Greece during World War I. The 3,000 objects were only partially documented at the time, and Shapland has to match up objects with scattered notes and references in soldiers’ letters. One of Shapland’s volunteers spent a year cataloging some 2,000 potsherds, while he himself has written several articles on the collection.

Much of this information has made it into the museum’s online database, with a description of every artifact in the collection, including accession date, who donated or found it, plus a photo.

“Now we are packaging the collection to make it easier for the public to navigate. This is the second phase of the operation,” Shapland said.

ANOTHER WAY that staff interacts with the public is by answering questions. Unusually for such an institution, part of the British Museum’s mission statement is to answer every question posed to it, whether some detailed query by an overseas academic or a basic question from the public.

Taylor’s department is deluged with questions, and each curator spends four to five weeks a year dealing with them. The Egyptologists often have to clear up misperceptions about mummies’ curses and pyramid power. Sometimes people will bring in “genuine ancient Egyptian artifacts” they bought overseas, and Taylor will have to give them the bad news that they bought a fake, although they should be consoled that they didn’t break any international antiquities laws by taking a real artifact out of Egypt. Taylor also recalls an interesting letter from an engineer who came up with a brilliant and plausible explanation of how the Egyptians built the pyramids; the only problem was that there was no evidence that the Egyptians did it that way.

While one might think this sucks valuable time away from their work, Taylor likes fielding questions because it helps gauge what the public is interested in and forces the staff to keep well-grounded in the basics of their field.

While curators are generally seen only at talks, the museum’s volunteers are at the front line of interacting with the public. One of their most popular jobs is at the Hands-On displays, where volunteers pass around genuine ancient artifacts for people to examine. In her second month of volunteering, Anne Richmond-Patrick is already showing off Anglo-Saxon beads and Merovingian belt buckles, having studied a ream of material so she can answer potential questions.

It’s not easy to become a volunteer. The museum doesn’t take applications except during periodic recruitment drives, and it does not accept all applicants. Volunteers also have to go through a rigorous training process. While a background in history or archaeology isn’t required, there is a steep learning curve that includes lectures on everything from archaeology to storytelling. Richmond-Patrick fits in her volunteering and training amid her job at a bank.

She has volunteered for many organizations, ranging from her church to the RSPCA, and is excited that her new work allows her to revisit her love of history, in which she has a degree. “It’s a real privilege to be allowed to work here,” she says.

It is a sentiment echoed by everyone at the British Museum, staff or volunteer.

Comments