[caption id="BessofHardwick_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

DAVID OAKES

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img1" align="alignleft" width="578"]

©NATIONAL TRUST PHOTOGRAPHIC LIBRARY/JOHN BETHELL/THE IMAGE WORKS

John Entwistle, steward at Hardwick Hall near Chesterfield, is a spry fellow. Eighty-seven he may be, but he took the tilting, old oak steps of the North Staircase up onto the roof in no time. I thought of Bess of Hardwick, aged 70 when she moved into the hall in 1597, swishing in her long skirts with equal determination.

The Peak District air is certainly energizing. Pale sun lit the translucent green diamonds of original 16th-century glass in the windows as we headed off the usual visitors’ route to Bess’ rooftop banqueting chamber, where she would relax with guests over sweetmeats.

A generous helping of satisfaction must have aided her digestion as she surveyed the panorama. Hardwick Hall, “more glass than wall,” was the acme of her many building achievements, and an architectural wonder of the Elizabethan world. Below, she could see Hardwick Old Hall on the site where her life had started: just a few steps away, but a leap of progress unimaginable for a woman of her era. The daughter of an impoverished gentleman farmer, she had married four times, survived personal and political intrigues, wheeler-dealered her way to huge wealth and become arguably the second most powerful woman in England after her friend, Queen Elizabeth I. Perhaps recognizing a kindred spirit, Elizabeth declared, “I assure you, there is no lady in the land I better love.”

In this 400th anniversary year of Bess of Hardwick’s death, Visit Peak District & Derbyshire tourism, rightly proud of the region’s most dynamic daughter, is marking her life and legacies with a season of activities. Royal Crown Derby has also created a special Bess of Hardwick five-petal tray, in memory of the woman who bequeathed a “dynasty of dukedoms.”

“She would have had to be tough to survive in the 16th century,” Entwistle says. “She has been accused of being manipulating, ruthless, unwomanly. But her account books show she was also a very generous and nice lady. She often gave gifts to family, friends and servants.”

Portraits of Bess at Hardwick Hall are equally contrasting: On the one hand, there’s the pretty, almost demure 30-something redhead; on the other, a formidable old widow in her 70s, bedecked with pearls. The magnificent High Great Chamber with its effusive frieze and tapestries proclaims status and wealth. Small cloth patches on her Gideon Tapestries, added to hide a previous owner’s coat of arms, suggest a pennywise operator.

I spent two days touring the Peak District, Chats worth, Buxton and Derby on the trail of this enigmatic lady. It’s rugged countryside, particularly in winter, but the moors blaze with purple heather in summer. Maybe such spirit of place infuses people with strength and determined beauty.

Down the road from Hardwick Hall I dropped into The Hardwick Inn, erstwhile home of one of Bess’ estate craftsmen. Over lunch, Ellen Outram of Visit Peak District & Derbyshire gave me the story of Bess’ early life.

Elizabeth Hardwick was born circa 1527, the third daughter of squire John Hardwick. The family’s manor farmhouse stood on the site of Hardwick Old Hall. John died even before her first birthday, leaving each of his daughters £26 13s 4d. Bess became a lady’s companion at age 12, married Robert Barlow when she was 15 and by 16 was a widow. A court battle ensued for her modest widow’s dower—the first of many legal wrangles she would win.

By 1545 she was a waiting gentlewoman in the household of Lady Frances Grey, mother of the ill-fated Jane, at Bradgate Park, Leicestershire. This introduced her into the upper circles of Tudor society and, still only 19, she met Sir William Cavendish, marrying him in 1547. Sir William, 40 and twice married, was treasurer of the King’s Chamber, with a vast fortune and a property portfolio across five counties. In return for social advancement, Bess traded youth and, in 10 years of wedlock, eight children: Three sons and three daughters lived beyond infancy. She would have no more children, but her Cavendish offspring proved ample for playing the chessboard of life.

“I believe Bess was in love when she married Sir William; at that age she wasn’t thinking of building a dynasty,” Outram says. “He taught her account-keeping and estate management [at his Northaw property near St. Albans]. She was obviously very entrepreneurial. I also think Cavendish was the husband that Bess most manipulated. She got him to sell all his existing property and buy land in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, including Chatsworth [in 1549 for £600].” Together they began to build a mansion there.

So, Bess was back on home territory in Derbyshire, only now far richer: in land, experience and business acumen, well able to manage Sir William’s interests while he was absent on government work. She quickly learned the way forward in the Tudor world—godparents for their children chart the changing political winds, including Lady Jane Grey, Princess Elizabeth and Queen Mary.

But it wasn’t all cold politics for Bess. After the unwilling queen Jane Grey lost her head, Bess kept a portrait of her childhood friend beside her bed for the rest of her life.

Sir William, Bess’ “most dear and well beloved husband,” died in 1557, leaving her with a life interest in Chatsworth and a large proportion of his property—plus a £6,000 debt to the Exchequer for apparent errors in his Privy Chamber accounts. A widow with few legal rights, six young children and two stepdaughters, Bess nevertheless challenged the State and, despite her baggage, hooked another husband in 1559. “She wasn’t a dazzling beauty, but she must have been charismatic,” Outram concludes.

Husband number three, William St. Loe, was captain of the new Queen Elizabeth’s personal guard; soon Bess was a Lady of the Privy Chamber and close royal friend. The Crown reduced the Cavendish debt to a manageable £1,000. Bess’ personal finances were further boosted in 1565 when St. Loe died, leaving her much of his property outright, to the great displeasure of his family. Bess got her dues after a fight, and in 1568 she married George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury—her most sensational match of all.

Shrewsbury, at 40 a few months younger than Bess, was head of one of England’s grandest families. Farmer, ship-owner, ironmaster and more, he was the richest man in the country in terms of landholding, with the main part of his property in the Midlands like Bess. “Their union was clinched by a triple marriage,” Outram adds. “Shrewsbury wedded Bess, his second son married her daughter, Mary, and his daughter married her eldest son, Henry. Quite clearly, Bess was building her dynasty now!”

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img2" align="alignleft" width="1024"]

DAVID OAKES

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img3" align="alignright" width="777"]

©PATRICK WARD/ALAMY

“Quite clearly, Bess was building her dynasty now”

But shadows approached to spoil the party. Lunch done, I headed off to Buxton, some 28 miles west, for my next installment.

In 1569 Queen Elizabeth gave Shrewsbury the unenviable task of guarding the Queen of Scots, who had fled across the border into England. Over the next 15 years, the burden would help destroy his marriage to Bess as they moved their difficult guest between their homes at Tutbury Castle, Sheffield and Wingfield manors, Chatsworth and Buxton. Bess often sat sewing and chatting with Mary—should circumstances alter, it did no harm to be on friendly terms with a claimant to the English throne (and their needlework came in handy later for furnishing Hardwick Hall!).

Mary was brought several times to Buxton to take the spa waters. I stayed at the Shrewsburys’ house, now the Old Hall Hotel. Most of the original building is hidden behind later work, but a John Speed map of Derbyshire opposite reception includes a drawing of the fortified tower that once was, and there’s a bedroom where Mary reputedly slept. Nip along the road to the Tourist Information Centre, backing onto the Old Hall, and you can peer through a glass window to the very spring of warm water that the Scottish queen and her keepers may have enjoyed.

Next day, I headed back east to Chatsworth, where Bess hosted Mary seven times between 1570 and 1581. Visible remains of Bess’ home are few, following 17th and 18th-century rebuilding, but Mary’s Bower, a plinth once surrounded by shallow fishponds, was a picnic spot the two women favored. I also climbed the wooded hill to the Hunting Tower, where Bess and Mary sat with their never-ending embroidery, watching the menfolk chasing deer across the countryside. You can hire the tower as a holiday let.

Shrewsbury’s task as gaoler stretched his finances and nerves to breaking point.

He also fell out with Bess when, without the necessary permission from Queen Elizabeth, she helped arrange the marriage of her daughter Elizabeth to Charles Stuart, Earl of Lennox. The latter’s descent from Henry VII made the newlyweds’ daughter Arbella, born 1575, a claimant (after James VI of Scotland) to the English succession should the Virgin Queen expire. Bess had considered the match worth the royal wrath that ensued. Eventually, Bess was forgiven and when both parents died young, she became Arbella’s guardian, with continuing hopes for the future.

Bess and her husband further argued over ownership of Chatsworth and the amount of time and money she spent building there. Shrewsbury died estranged in 1590, three years after seeing Mary executed. His widow, now in her mid-60s, had finished her marital leapfrogging to wealth and status, but her building mania was in full flower.

In the latter years of Shrewsbury’s life, she had retreated to Hardwick Old Hall (purchased from her brother’s estate in 1583) and remodeled it. By 1590 she was laying the foundation stones of her much grander new hall, where my journey into her life began.

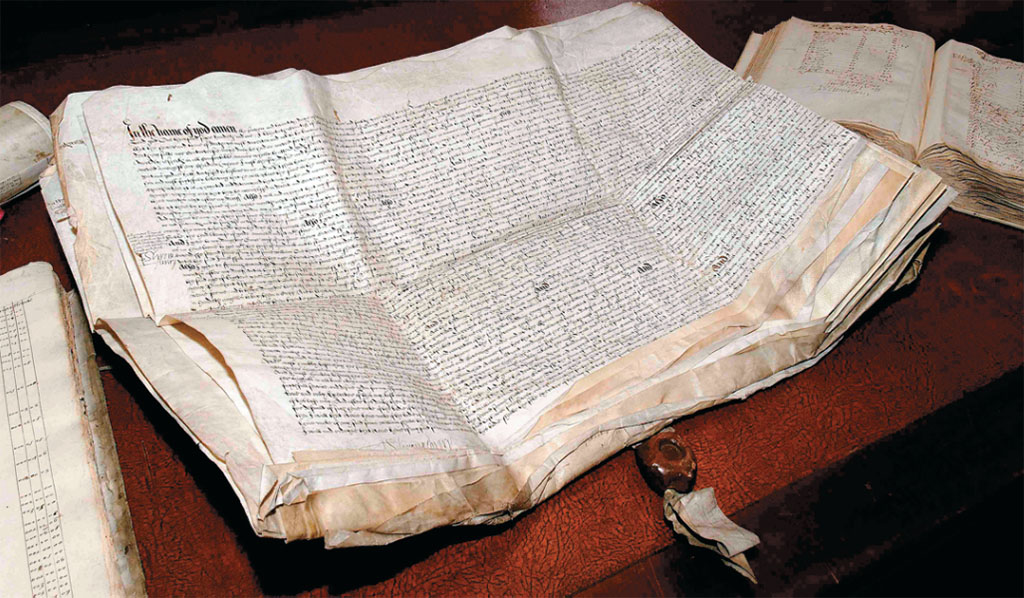

Away from the glorious staterooms on public view at Chatsworth, I headed along service corridors to the Study Room where archivist Stuart Band had brought out Bess’ building accounts for me to see. “Each page of accounts is checked and signed in Bess’ hand. Sometimes, when you turn a page, grains of sand used to dry the ink still fall out,” Band says. “All the craftsmen are named and the records show in great detail how much material for Hardwick Hall came from Bess’ greater estate, ironworks, quarries, coal. She had her own glass made at Wingfield.”

Visiting in “Bess Country”

- INFORMATION: For useful information on Bess of Hardwick locations in the Peak District and Derbyshire, to create your own itinerary or to find accommodation and events, see www.bessofhardwick.co.uk. General information can be found at www.visitpeakdistrict.com.

- TRAVEL: Siân Ellis traveled to “Bess Country” by CrossCountry, which runs fast and frequent services between Plymouth, Bristol, Derby and Chesterfield for the Peak District. Tickets, which include seat reservations, may be purchased online at www.crosscountrytrains.co.uk. or by visiting any staffed rail station.

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

BRITAINONVIEW/NTPL/DEREK CROUCHER

‘Those vast, costly windows dazzled the Elizabethan world with their ethereal symmetry’

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img5" align="alignleft" width="1024"]

NATIONAL TRUST PHOTO LIBRARY/ALAMY

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img6" align="alignright" width="1024"]

©HEADLINE PHOTO AGENCY/ALAMY

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img7" align="alignleft" width="1024"]

DAVID OAKES

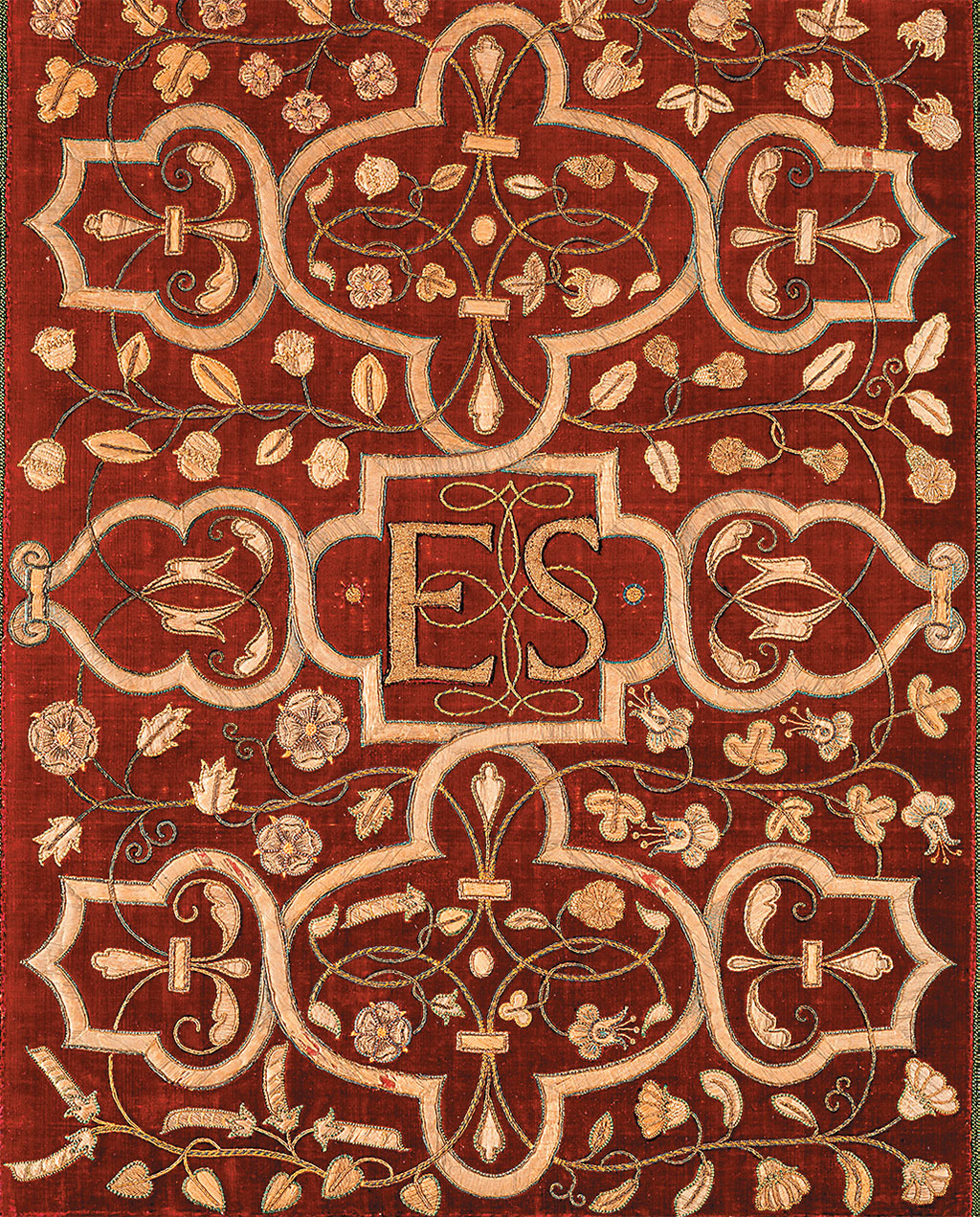

Those vast, costly windows dazzled the Elizabethan world with their ethereal symmetry, following a pioneering design from architect Robert Smythson. Hardwick Hall was Bess’ life achievement writ large, her huge carved initials “ES” (Elizabeth Shrewsbury) atop the turrets for all to see. Her secret wish was that Arbella might one day be queen, and here was a worthy palace for her to stay. Though she did everything she could to nurture and maneuver her young charge, she failed in this, her greatest ambition. Arbella would later die in the Tower of London.

Bess left nothing to chance, and certainly not her funeral and legacy. Band showed me her will with inventories for Chatsworth and Hardwick Hall, written several years before her death at age 80 in 1608. She handed the bulk of her property to her favorite, second son William Cavendish. “He was hard-working and careful, unlike her eldest son, Henry, who was a bit of a wastrel. She believed the future of the dynasty lay with William,” Band says. She instructed that her funeral should be “not over sumptuous.” It cost a staggering £3,257 (around £375,500 today).

A 29-mile jaunt south, Derby Cathedral (All Saints Church in Bess’ time) is the formidable lady’s final resting place. Here I met Derek Limer, Keeper of the Treasures. “People came from far and wide for the funeral,” Limer says. “Black cloth was ordered to dress all her household, servants and the poor from the almshouses she had endowed. The church was draped in black and a thousand black pins were bought to hold together the material.”

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img8" align="alignleft" width="1024"]

DAVID OAKES

[caption id="BessofHardwick_img9" align="alignright" width="1024"]

DAVID OAKES

The cathedral’s medieval tower would be familiar to Bess, but the light Georgian interior would be a surprise. She is buried in the crypt, and her ornate black-and-pink marble monument is in the body of the church. Planned by Bess and designed by Robert Smythson, it shows a life-sized regal figure of some 5 feet 4 inches. The inscription, added 69 years later, erroneously records that she died in 1607, aged 87. You can just hear her tutting at such carelessness.

Like Elizabeth I, Bess was ahead of her time. Smart and diligent, she made good in a turbulent era, turning her father’s £26 13s 4d into a fortune, and building grandiose homes. Moreover, her social climbing continued even after her death, thanks to the judicious marriages of her children. Their descendants would carry her DNA to the Dukes of Rutland, Devonshire, Newcastle, Portland, Norfolk, Baron Waterpark and the Earls of Pembroke and Kent, among others. The present Royal Family can trace a line to her through the late Queen Mother.

Bess’ son William was a backer of the Virginia Company, and no doubt she would have approved of the go-getting inclinations of the nation that developed across the pond. Through William’s descendants, Chatsworth grew in glory, Old Hardwick Hall fell into romantic ruin (now cared for by English Heritage) and Hardwick Hall eventually passed to the National Trust in 1959, almost as Bess left it. The genteel Buxton we see today bears the architectural imprint of the spa-loving Cavendish family: the handsome Georgian Crescent, domed Great Stables and Victorian Pavilion Gardens. However you look at it, Bess’ story will run and run.

Comments