National Museum of Scotland

BACK IN 1780, at the height of the Enlightenment, an august group of Edinburgh luminaries hatched a plan to collate their archaeological finds. The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland collaborated with the Industrial Museum of Scotland to create a new super-museum . The building was erected in 1854 with the kind of swaggering grandeur the Victorians excelled in. A whole host of confusing names later, this enigmatic collection of collections became the National Museum of Scotland.

As the various collections, from the original industrial and scientific slant to the 19th- century obsession with natural history, grew and merged, so the building that housed them was forced to adapt. Partitions were built, storerooms filled-in, exhibits shoved wherever they would fit.Gradually, the airy, wrought iron structure, with its birdcage ceiling and light-filled atrium inspired by the Crystal Palace, became clogged to the point of bursting .And, sadly, so did some of its objects. The superb collection of taxidermy became moth-eaten; a motorcar suddenly found its way into a room full of ethnographical items. Many of the most incredible objects sent from across the globe went straight to storage and never got shown at all.

When a second building was opened across the way in 1998, the older part of the museum effectively went into a dusty slumber, the majority of its visitors never venturing beyond the ground floor.

Thanks to a £46.4m redevelopment plan, this gradual decline has been sent into reverse, and the original Victorian building has been allowed to breathe again. With a new street level entrance hall, the original lobby and classic Edinburgh granite steps have been freed for proper display again. Bricked up archways have been opened and partitions torn down, paring it back to a state its Victorian founders would have recognized, giving the building 50 percent more public space at the same time.

They’ve been able to go through their store cupboards, too. More than 80 percent of the 8,000 objects on display, from natural history to art and design, from Scotland’s vision of the world to the world’s vision of Scotland, are on show for the first time, and they have been carefully curated to actually mean something, rather than randomly squeezed in somewhere.

While I confess to being extremely fond of the old-fashioned, loads-of-things-in-a-display-case style of museum, these days interpretation is as important to most people as the items themselves . Curators have been careful to cater for the different types of visitors, from families to serious historians. The museum holds it grand reopening on July 29, 2011. www.nms.ac.uk

—Sandra Lawrence

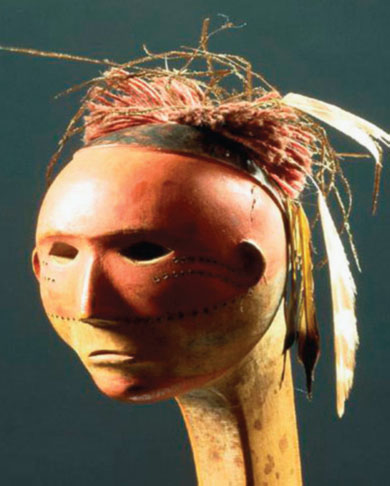

[caption id="BeyondtheBookshelf_img1" align="aligncenter" width="390"]

[caption id="BeyondtheBookshelf_img2" align="aligncenter" width="375"]

[caption id="BeyondtheBookshelf_img3" align="aligncenter" width="992"]

COURTESY OF NATIONAL OF SCOTLAND

BOOKS

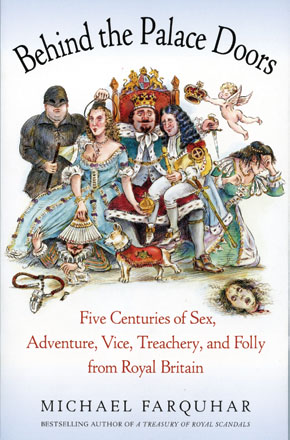

Behind the Palace Doors: Five Centuries of Sex, Adventure, Vice, Treachery, and Folly from Royal Britain by Michael Farquhar, Random House, New York, 384 pages, softcover, $15.

[caption id="BeyondtheBookshelf_img4" align="alignright" width="290"]

Unpacking the Gossip of History

INDUBITABLY. Over the last 500 years there certainly has been plenty of sex, adventure, vice, etc. behind the doors of the royal apartments. And sometimes in public, too. In the proverbial nutshell, Behind the Palace Doors is a brief history of the monarchy from the time of King Henry VIII, focusing on the salacious and interesting bits. It’s the human interest story. Michael Farquhar hasn’t really done something new here, but what he has done, he has done very well.

Taken as a whole, the narrative can be read as a cautionary tale&madsh;the moral arrogance that results from relatively unfettered absolute power. It is amazing how much the monarchy itself seems to insulate its members and hangers-on from the moral niceties and human compassion that is a measure of less rarified humanity (such as the rest of us). Atomistically, each brief, lively chapter captures light-heartedly the foibles and follies of monarchs and their kin. From “Bloody Mary’s Burning Desire” and George ill’s “The Reign Insane” to the randy exploits of such libertines as his son, George IV, and Charles II, who “scattered his maker’s image across the land,” Farquhar takes us behind the door indeed.

This book would make a terrible way to begin learning the history of the monarchy, let alone the history of Great Britain. For readers who already know the sweeping story, though, it’s a rollicking expose, a colorful detailing of the juicy gossip one heard in the whispers of history. Fast-paced, clearly written and full of wit, Behind the Palaces Doors is fun.

Westminster Abbey–The Royal Venue

MANY FIRST-TIME VISITORS find themselves on a whirlwind tour of Westminster Abbey as part of a desperate student rush to see every London landmark in a day and a half. They “ooh” and “aah,” tick it off their list and rush over to the Tower. On subsequent visits, it becomes “something tourists do” and often gets overlooked for a serious in-depth second visit.

In a way, Westminster Abbey is almost too important for its own good. It’s not just visitors, of course. Every British kid has to do the obligatory school-trip traipse before consuming sweaty sandwiches and trudging over to see the Houses of Parliament. Most never return. I know, because I’ve just described myself. And having been dragged round Westminster Abbey as a child, I didn’t go again until a couple of years ago when some visiting American friends expressed a desire to do the “basic” circuit. Not only was the abbey worth a second visit, I’ve taken another since then, and I still haven’t seen everything.

Admittedly the cost can be a bit off-putting. £16 per person is quite steep; so, if you’re going to do it, make sure you give it plenty of time—there is a coffee shop in the cloisters if you’re flagging. And if you’re in that kind of money for a penny, you may as well stay in for a pound. Treat yourself to a verger-led tour at another £3, and see places you don’t even get to glimpse if you’re a bog-standard punter.

It’s easy enough to wander around Poets’ Corner or the cloisters on your own, and you really shouldn’t miss the bizarre funeral effigies in the museum; but to really get the most out of the Abbey’s architectural big-hitters, such as Henry’ VII’s Lady Chapel or the choir, an expert guide is invaluable.

[caption id="BeyondtheBookshelf_img5" align="aligncenter" width="660"]

COURTESY OF WESTMINSTER ABBEY

I recommend getting there a little early for the verger’s tour, if only to pick up a free audio guide. Stand in the crossing (the bit just in front of the altar), press 200 to hear a heart-filling version of William Walton’s Jubilate Deo, sung by the Westminster Abbey Choir, and immerse yourself in 1,000 years of history. The verger will bring you back here, but it’s worth spending time enjoying the extraordinary Cosmati pavement. The last time the Abbey was used for a Royal Wedding, back in 1986, by Prince Andrew and Sarah Ferguson, this fabulous medieval mosaic was still lying forgotten under floorboards. A major conservation program has seen it painstakingly brought back to life. And what a life. The floor is believed to represent the Universe, and it predicts the date of the end of the world. Of course, it’s probably not a terribly accurate prediction, since it’s largely based on computing the life spans of mythological creatures, but as a work of art it is breathtaking.

Everywhere you look, there’s someone famous interred. Among the more notable of 3,000 dead folk under your feet, Elizabeth I lies in a side room, uneasily united with her half-sister Mary. Richard II, Mary Queen of Scots, Henry V, Henry VII; there are more monarchs buried here than you can shake a stick at, and all of them were crowned here. The verger has all the dates, the main one being 1066, of course, when William I made it very clear to the English that he was their rightful monarch by having himself crowned in the resting place of Edward the Confessor.

One of the places you get to sneak a peek at if you’re on a tour is Edward’s magnificent tomb, off-limits to all but pilgrims otherwise. It was once highly ornate, but in the days before official souvenirs, and medieval pilgrims being what they were, most of the decoration below the stretch of an arm has now disappeared.

If every coronation since 1066 has taken place at Westminster, it’s not true for Royal weddings. It’s a forerunner on a bride’s shortlist, but it’s not a foregone conclusion. The Queen was married here; Prince Charles was not. That’s not to say it doesn’t have many traditions associated with it, and not all of them stretch back into the mists of time. One charming gesture was begun by Her Majesty the Queen Mother. The memory of her brother, Fergus, who had died in the Great War, was still raw when Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon walked up the aisle at Westminster in 1923. The tomb of the Unknown Warrior had been completed recently. Before she began the long walk through the nave, she stopped, laid her bouquet on the grave and then continued her path around the stone (it is the one memorial no one ever walks on in the Abbey). Every Royal bride since has left her bouquet with the unknown soldier.

Westminster Abbey has been a tourist attraction since its foundation, and it can get extremely busy. Careful timing is worthwhile—January and February are quiet months in London, if you can tolerate the almost guaranteed ghastly weather; Christmas, Easter, July and August are the busiest times. Picking an early weekday and arriving as soon as possible after opening time at 9:30 a.m. is the best way to ameliorate the often heaving crowds at other times. www.westminster-abbey.org

—Sandra Lawrence

Comments