“The art of the butler is seen by many people as being old-fashioned, but nothing could be further from the truth,” says Grant Harrold— and he should know.

Editor's note: Originally published in October 2013.

A butler and member of the Royal Household of Their Royal Highnesses The Prince of Wales and The Duchess of Cornwall from 2004 to 2011, Harrold began butlering on a privately owned Scottish estate in 1997, and he has worked in stately homes across the UK. He now runs royal butler training and etiquette company Nicholas Veitch, working with the Queen’s great-niece, HRH Princess Katarina of Yugoslavia and Serbia, and has an exclusive butler recruitment agency. In September, he launched the Royal Butler School in partnership with Blenheim Palace, the baroque Oxfordshire home of the Duke of Marlborough, to train individuals to enter today’s profession.

“These days we are not only experiencing many more inquiries across the traditional markets of the USA and Europe but there’s increasing demand from China," he says. “While most of our placements are with Royal families and wealthy individuals, we also receive many requests for attendance at prestigious events and private dinner parties.”

Alongside key attributes of “loyalty, discretion, confidence, and positivity,” Harrold says, a well-trained butler never panics. “The role of the 21st-century butler is somewhat different from those you see in TV dramas such as Downton Abbey and Upstairs Downstairs, where the butler is a senior figure able to call upon the support of dozens of under-staff.

Grant Harrold. NICHOLAS VEITCH

“These days, butlers have to be able to turn their hand to anything. One minute the butler will be laying a table for breakfast, the next he will be cooking the breakfast, after which he may be valeting (ironing) or booking appointments and running errands for his employers. The butler has to be skilled in doing everything, and to an exceptionally high standard. There was also an occasion when I was asked to dance by the Duchess of Cornwall, at the Ghillies Ball at Balmoral Castle. Thankfully I had taken dancing lessons just in case this occasion arose … a butler must be ready for anything.”

For centuries the discreet, smooth-running domestic machinery of an army of servants was a defining feature of British country houses. While today those armies may have been reduced to multi-tasking platoons, they nevertheless continue to perform their duties: Blenheim Palace, for example, boasts an unbroken 300-year tradition of butlers.

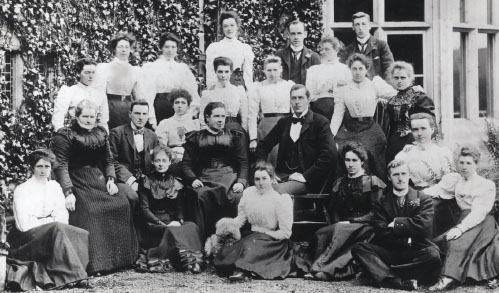

The staff at Cragside in the Lake District (now National Trust) gathered for this picture in 1888. NATIONAL TRUST

Even before Downton Abbey hit our screens, stately homes had realized that public visitors are as much fascinated by the intricacies of life Downstairs as they are impressed by the luxuries of life Upstairs, and so pushed open the green baize door to allow us to follow in the historic footsteps of the Carsons and Mrs. Hughes of yesteryear. Here, after all, is where many of our forebears worked; some two million people out of a population of 40 million were domestic servants as late as 1901.

Historic behind-the-scenes snoops at Blenheim Palace include private apartment tours (April to September) into a world of backstairs and bells whose ringing summoned servants to rooms through the house. In her book Blenheim and the Churchill Family, Henrietta Spencer-Churchill, sister of the current Duke of Marlborough, records that in the time of the 4th Duke (succeeded 1758) up to 88 indoor servants kept the Upstairs in comfort. Alongside familiar personnel like head cook and kitchen maid, there was even a “running footman,” whose job was to run in gold-fringed breeches at a steady pace of seven miles an hour in front of the Duke’s coach (annual pay, £20).

In medieval and Tudor households, staff had been very much on display as a show of status and wealth; sons of gentry often served, learning protocol as if at a finishing school. By the 18th and 19th centuries, however, the heyday of Upstairs Downstairs culture, lower servants at least had become invisible. The “green baize door” separating the worlds of master and servant appeared in the 18th century to dampen sounds from kitchen and scullery; the social division was also writ large in house design: cramped attic bedrooms and basements, hidden tunnels and gloomy servants’ corridors contrasting with the glittering chandeliers and grandeur of staterooms.

A turn around the domestic offices and servants’ quarters in the mansion of Cheshire’s Tatton Park gives a comprehensive picture of this “world within a country house world,” when the Egerton family employed some 40 indoor servants at the end of the 19th century. The tiled, stone-floored scullery and kitchen are strategically placed at the western end of the house for delivery of supplies from the walled garden and home farm—the aim was to be self-sufficient—and within range of the dining room without being so close that cooking smells infiltrated family rooms. Wine and beer cellars, and a coal store, jealously overseen by the butler, catering to family comforts.

The butler’s pantry, here at Uppark, was a combination office, sitting room and bedroom for the head of the household staff, always centrally located Downstairs. NATIONAL TRUST IMAGES/NADIA MACKENZIE

The sheer amount of elbow grease involved to keep grand homes functioning, before labor-saving devices eased the burden, was (literally) breathtaking, as servants staggered upstairs with hot water to fill baths, raked out ashes to lay fires and endlessly polished silverware and cutlery. Correct care of linen was vital to good housekeeping, and there were mountains of it. A 1792 inventory at Georgian Shugborough in Staffordshire includes 85 damask tablecloths and 92 dozen damask table napkins, not to mention countless tea napkins, breakfast cloths, bed linen, and clothes.

Three laundresses labored for six days a week. Today you can step back to 1871 in the wet and dry laundries to sympathize with costumed maids busy washing and scrubbing in copper and tub. Then, compare that to a lot of servants cheese-making, milling, brewing, and baking.

Being in service was a respectable norm of life and, through hard work, at least usually came with food and lodging. “Downstairs” was as highly stratified as society at large. The steward or butler topped the pecking order, with first footman (noted for good looks and fine livery) as his right-hand man, and the housekeeper organized female staff, through cook and chambermaids down to scullery-maid scouring plates, dishes and chamber pots. Valet and lady’s maid, hired directly by the master and mistress of the house, stood slightly apart.

Peep into the butler’s pantry and housekeeper’s room at Uppark House, West Sussex, from which each orchestrated their duties. Manuals made clear what was expected, with the Servants’ Book of Knowledge (1733) warning a butler should “never suffer strangers to come into the place where [silverware] is kept.” The Gentlewoman’s Companion (1675) counseled that a housekeeper should ensure staff “keep good hours in up-rising, and lying down, and that no Goods be either spoil’d, or embezzl’d.” Everything from spices to linen was locked away, with the bunch of keys at the housekeeper’s waist a symbol of her authority.

Massive households demanded huge kitchens, not only to serve elegant formal meals for family and guests but to feed the entire household staff. TATTON PARK

Kitchens were the frantic fulcrum of any country house. The kitchens at Petworth House, West Sussex, sating the appetites of nearly 30,000 guests in 1829 alone, remain a sight to behold, boasting more than 1,000 copper pots and pans, a traditional roasting range, and bain-marie. A cook needed to be every bit the feisty figure suggested by the Servants’ Practical Guide (1880), who “will not brook fault-finding, or interference with their manner of cooking.” The Old Kitchen at Holkham Hall, Norfolk, also conjures up magnificent visions of lavish feasts. Imagine the two footmen, who every morning pushed a trolley with a copper of bubbling water and eggs from the kitchen to the nursery: by the time they arrived, the eggs were boiled to perfection.

As butler and housekeeper, Carson (Jim Carter) and Mrs. Hughes (Phyllis Logan) ruled the Downstairs roost at Downton Abbey. NICK BRIGGS/CARNIVAL LTD FOR MASTERPIECE

To discover the people behind the servant roles, visit to the mansion of Erddig, in Wrexham, North Wales. A unique series of 18th and 19th-century servants’ portraits, commissioned by the Yorke family that lived here, records the mutual loyalty that could develop between master and staff. Verses written by the mansion’s owners celebrate the subject of each picture, from blacksmith William Williams (“Our Erddig Smith, who 50years, Was Surgeon-general to the gear”) to housekeeper Mary Webster (“She knew and pandered to our taste, Allowed no want and yet no waste”).

Elsewhere, relations between family and servants could get too cozy—tales of seductions of housemaids who subsequently “disappeared” are legion. More rarely, the social convention was defied: When Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh of Uppark, fell for the comely dairymaid Mary Ann Bullock and proposed in 1824, he bizarrely suggested she indicate acceptance by cutting a slice out of the leg of mutton sent up for his dinner later that day. Naturally, she cut the slice and swapped butter-making for a whirlwind education in Paris and marriage to Sir Harry the following year.

Schoolteachers dress in the roles they are learning about during a National Trust visit to Erddig, North Wales. NATIONAL TRUST IMAGES/ARNHEL DE SERRA

As viewers of Downton Abbey know, upheavals of world war, social change and financial challenges in the early decades of the 20th century signaled that the heyday of Upstairs Downstairs culture was over. Service nevertheless prevails in modern form in great estates from Blenheim Palace to Chatsworth in Derbyshire, while the rich and royal around the world still seek out butlers and housekeepers—with a special cachet attached to those trained in Britain.

Why? Last word to “The Royal Butler” Grant Harrold: “English butlers are quite rightly recognized as the best in the profession. After all, the British taught the world etiquette and good manners and these are timeless social qualities at the very heart of all our butler courses.”

Delve Downstairs

Fancy butlering or brushing up on etiquette? Find out more about the Royal School or Butlers, as well as fascinating talks and tuition by Grant Harrold, at www.nicholasveitch.com and www.theroyalbutler.co.uk.

Head Downstairs at:

Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire

Holkham Hall, Norfolk

Erddig, Petworth, Shugborough, Tatton Park and Uppark

* Originally published in Oct 2013.

Comments