[caption id="BitsofBooksAboutBritain_img1" align="aligncenter" width="126"]

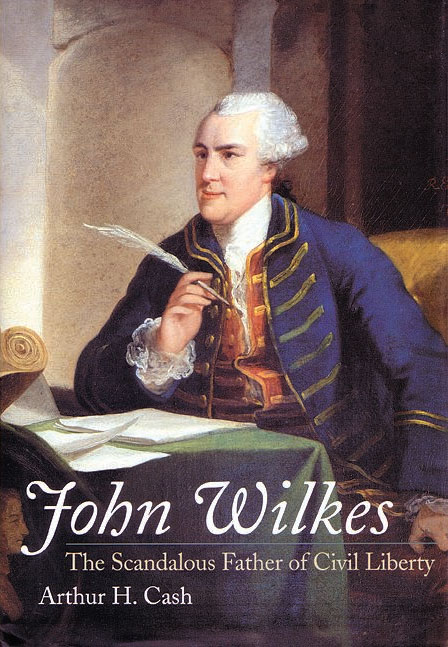

JANE AUSTEN’S PRIDE AND PREJUDICE has long been one of my favorite novels. Though all six of her novels are masterpieces of wit and style, Pride and Prejudice remains the most popular. Little wonder it finished No. 2 in our poll of the 10 most British books. Austen’s loving and deft portrayals of gentry life in the village world of the late 18th century are among the greatest of English novels. From important fiction, we then move on to reviews of important nonfiction. After a career on the front lines of British diplomacy and foreign policy, Chris Patten is in a unique position to assess the relationship among Britain, the United States and Europe. Patten’s Cousins and Strangers is a significant read. We also look at the colorful British statesman John Wilkes, an unsung champion of American independence in Parliament and of many civil freedoms we espouse.

Pride and Prejudice, by Jane Austen. Available in many editions, both soft and hardcover.

[caption id="BitsofBooksAboutBritain_img2" align="aligncenter" width="450"]

JANE AUSTEN’S Pride and Prejudice opens with one of the most famous first sentences in English literature. And oh, what a roller coaster of a sentence it is: “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” What could be more authoritative than those first words: “It is a truth universally acknowledged.” The reader anticipates some moral apothegm, only to discover a debatable opinion on the desirability of marriage. Even that “truth” arrives after a swoop in which the man of “good fortune” is surprisingly “in want.” Surely not. Wealthy men want for very little, and certainly not for a wife—any old wife—though a particular wife may be a different matter.

So this universally acknowledged truth is not universal after all. Quite the reverse. As readers soon discover, it is single women without fortunes who are in want of husbands: seriously in want, since the prospects for unmarried women of the middle class in 18th- and 19th-century England were far from rosy. Genteel poverty was the best that could be expected, meaning virtually dowerless young women like Elizabeth “Lizzy” Bennet and her older sister, Jane, faced both hardship and emotional disappointment if they could not find husbands. A mother such as Mrs. Bennet, with five daughters to marry off, had a hard task finding husbands for them all. Indeed, if anybody universally acknowledges the desirability of single men with fortunes needing wives, it is just such mothers—Mrs. Bennet in particular.

Mrs. Bennet is so absorbed in her own concerns that she is unable to think about or even fathom the concerns of anyone else, so she assumes her wishes are universally shared. Jane Austen leaves her readers in no doubt that Mrs. Bennet is “a woman of mean understanding, little information and uncertain temper.”

But if Mrs. Bennet is invariably an embarrassment to her eldest daughters and her husband, her lack of perception is widely shared. Mr. Bennet has lots of sense, a deal of wit and a realistic assessment of his daughters’ characters. Yet he rarely exerts himself on their behalf.

Lizzy and Jane understand the world much better and judge much more soundly than either of their parents. But they, too, mistake intentions and misread people. What seems obvious to them—“universally acknowledged”—turns out not to be so. Jane believes in Caroline Bingley’s affection and Mr. Wickham’s innocence, and she shares Lizzy’s opinion that Darcy is haughty and obnoxious. Fundamentally, though, she believes—wrongly but lovingly—that people are good and well intentioned. Lizzy is much more skeptical, but the quickness of her perceptions and wit, which are her finest qualities, can also blind her, notably in her assessment of Darcy.

Thus Pride and Prejudice begins with almost all the characters locked into perceptions that they believe to be self-evidently true, but which prove to be at best partial, or sometimes wholly mistaken. By the end of the novel, those who have the ability to grow by responding to reality have a clearer sense of other people, and therefore good hopes for future happiness. Most obviously, these include Lizzy, Jane, Darcy and Bingley, and to a lesser extent Kitty and Mr. Bennet. As for Mrs. Bennet—one of the great characters of English literature—she achieves her ambition of marrying two of her daughters well, and who can begrudge her? She devoted her energies to that end, and if that was not exactly the whole duty of women of her era, it was certainly much of it.

Unless they married, the five Bennet girls would have had to live on about £100 a year after their father’s death. They could scarcely have supplemented this by earnings, since they had never been to school. Yet their lack of fortune constituted a disincentive to suitors. Young men in a comparable situation to theirs—Darcy’s cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam, and Wickham, for example—needed to find wives who had a dowry or inheritance. Thus financial considerations were important in marriage, so important that Charlotte Lucas willingly marries Mr. Collins because she values the home and independence he can provide.

[caption id="BitsofBooksAboutBritain_img3" align="aligncenter" width="231"]

To see these reviews and hundreds more by leading authorities, go to our new book review section at www.thehistorynet.com/reviews

But for Lizzy, financial security, while significant, could never have been all. She rejects two suitors who were more than eligible on financial grounds, prompting a major attack of hysterics by her mother when she refuses to marry Mr. Collins. Lizzy and Jane agree that they cannot marry anyone for whom they do not feel affection. So each must find a man of means whom she can love. Yet love alone is not enough. In her own way, the youngest Bennet sister, Lydia, loves Wickham, but his bad character added to his lack of wealth rank him with Mr. Collins as an object lesson in whom not to marry. To further complicate matters, social prestige is at least as significant as good character. When Darcy proposes to Lizzy, he reminds her he has had to ignore not just her lack of money but also her lower position on the social scale and the embarrassing behavior of her relatives—Mrs. Bennet and Lydia.

Marrying was therefore fraught with difficulties of many kinds. Yet though England’s social classes were stratified, though snobbery abounded, though standards for manners and behavior were strict, unlike in pre-Revolutionary France, the country was not legally divided into classes, and since at least the Renaissance it had always been possible for talented men to make their own fortunes in the church or in business. The prosperity of the era created a social ladder that British self-made men could move up. Wealth earned by one generation in trade became, a few generations later, wealth deriving from land and heritage.

But if people could climb the ladder and establish their families in some loftier spot, others could also fall off—as the Bennet girls come close to doing. This explains the anxiety that swirled round the related values of money, class, prestige and behavior. Marriage precipitated this crisis, creating stormy weather in some families, showering others with everything they desired. Thus it is marriage rather than male-oriented adventures or war that has always been the center of English fiction, and thus it is that Pride and Prejudice is one of the most cherished expressions of the complexity of a society capable of change and growth.

Jane Austen is sometimes criticized for never mentioning the Napoleonic wars that were raging while she was creating her novels. England was threatened with invasion, as she well knew because her brothers served in the navy, and one was married to a French aristocrat who had fled the guillotine. Nonetheless, the role of the soldiers who entrance Lydia seems to be to flirt rather than fight. But far from detracting from the novel, this lack of concern with contemporary events gives Pride and Prejudice its timeless air. Notably too, while Austen conveys Lizzy’s refusal of her suitors through witty dialogue between the characters, when Lizzy and Jane finally succeed, their penultimate happiness is described only in the most general terms, allowing readers to imagine the joyful communion between confessed lovers. Like two of Austen’s later novels, Emma and Persuasion, it is a novel of perfect poise about a social scene in ferment.

CLAIRE HOPLEY

Cousins and Strangers: America, Britain, and Europe in a New Century, by Chris Patten, Times Books, New York, 293 pages, hardcover $26.

CHRIS PATTEN is chancellor of Oxford and Newcastle universities and formerly European commissioner for external relations. Previously he served in Parliament for Bath, chaired the Conservative Party and was the last British governor of Hong Kong. And if his February 2006 appearance on the Charlie Rose Show reliably indicates his character, Patten seems to be an eminently sensible and courteous person.

[caption id="BitsofBooksAboutBritain_img4" align="aligncenter" width="449"]

As the subtitle of Cousins and Strangers implies, this work covers an extremely important topic in current affairs: the relationship among the United States, Great Britain and Europe. Patten offers a brief history of American/European relations since World War II, outlines our shared values and delineates some of our past successes on the world stage. He then suggests how America, Great Britain and Europe should act toward each other and the rest of the world in the 21st century.

According to Patten, the United States must give up its desire for empire, eschew its current unilateral stance in world politics, cooperate more closely with Europe and other allies, demonstrate a more progressive environmental stance and markedly increase its foreign aid to needy countries. Britain, he says, must assert more independence from America and integrate itself more fully into the European community. Europe, particularly France and Germany, must provide more military and political leadership to help reduce America’s unilateral influence and to do their fair share to calm the world’s hotspots.

Given Patten’s long history of public service and his personal demeanor, I expected to find this book highly informative and well argued. There are, after all, things to like in this book. For one, he realizes that the United States is far more interesting and complex than some European commentators give us credit for. Unlike Bernard-Henri Lévy in his recent book American Vertigo, for example, Patten has a nuanced view of America: “The surprising realization that you are very foreign in many parts of the United States comes hand in hand with the shock of discovering how difficult it is to generalize about the country as a whole.” He also has a nuanced view of American business, as he learned when serving in Hong Kong. American businesses there were “intelligently forthright about the importance of respecting and retaining the protection of Hong Kong’s liberties through the rule of law, strong institutions, and our first limited essays at democratic accountability. Again and again, they made the connection between economic liberty and political liberty.”

Among other positive aspects of the book are Patten’s often perceptive and witty observations about non-British leaders. Regarding Vladimir Putin, the author recognized early that the Russian leader had strayed little from his KGB past (but also that Europe had failed to moderate Putin’s ways). At a meeting about Russia’s treatment of Chechnya, Patten wrote: “We knew he was lying. He knew that we knew he was lying. He did not give a damn, and we all let him get away with it—on that occasion, and again and again.” Similarly, Patten’s physical description of North Korean dictator Kim Jong Il captures the whole oppressive condition of that poor country: “I half expected him to appear any moment through a trapdoor in the floor. . . .He looked extraordinary—a bouffant hairstyle all his own, in which each hair seemed to have been individually seeded in his scalp; built-up Cuban heels; shiny gabardine boiler suits.”

Unfortunately, the book suffers from some deeply wrongheaded observations about the United States. Patten’s idea that America has empire-like designs on the rest of the world is just one of several unfounded views. Unlike their 19thcentury European counterparts, American “consuls” do not long to sit in foreign capitals under ceiling fans doling out high-minded statements about civilizing the natives.

Finally, Patten’s suggestions for what America and Europe should do in the near future suffer from the presence of too many vague or “wonky” suggestions. America, he says, needs “a strong and credible United Nations.” He does not explain, however, how to wipe out the corruption that recently has sullied the world body nor how to get it to focus on the true violators of human rights rather than sanctimoniously going after the United States and Israel. As for Europe, he makes the obvious suggestion that it could save military expenses if only it “improved standardization and interoperability of equipment.” In short, this is a good, not great, book.

DAVID LANGLEY

[caption id="BitsofBooksAboutBritain_img5" align="aligncenter" width="449"]

John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty, by Arthur H. Cash, Yale University Press, New Haven, 482 pages, hardcover $37.50.

“IF YOU KNOW WHY you should read about John Wilkes, you may skip this paragraph. If you think that John Wilkes shot Abraham Lincoln, you may not.” So begins Arthur H. Cash’s lively biography of John Wilkes.

Politician, journalist and full-blown libertine John Wilkes was born to what he described as “a private gentleman…of inferior, but independent condition” in London in 1726. Wilkes was the second of three sons, and his father determined that he would be a man of leisure. Therefore, the youth was educated by tutors, attended Leiden and was married off to an heiress 10 years his senior. The couple separated after a very brief and unhappy marriage, yet from this union came a much-beloved daughter who was devoted to Wilkes.

Wilkes was first elected to the House of Commons in 1757, where he aligned himself with William Pitt the Elder and embarked on a lively political career that involved arrest, exile, two duels, prison and a weekly paper called the North Briton, in which he anonymously attacked the ministers and policies of King George III.

In 1764 Wilkes came under a general warrant of arrest for printing Vol. No. 45 of North Briton, an issue that was particularly critical of King George (it had long been suspected that Wilkes was the paper’s author and publisher, but nothing had been proved). The warrant was “general” in that it did not specify a suspect for arrest, so it allowed the king’s messengers to arrest anyone and confiscate anything. Forty-nine people were arrested, and the private papers of four individuals, including Wilkes’, were taken. Wilkes responded aggressively by suing the messengers for false arrest and the illegal seizure of private property. He helped others likewise file suit, and the result was the abolition of the general warrant.

Wildly popular with his constituents, Wilkes was reelected to the House of Commons three times while he was in prison. After his release, Wilkes was made sheriff of London, and served as Lord Mayor. He was also again elected to Parliament, where he championed freedom of the press, separation of church and state, religious tolerance, and suffrage for all English men, not just landed gentry. And he vigorously supported the American Revolution. He corresponded with numerous American patriots, including Samuel Adams and John Hancock, and Wilkes even surreptitiously contributed money to the cause. His writings and speeches were widely recognized and admired in the Colonies. Wilkes County and Wilkesboro, N.C., as well as Wilkes-Barre and Wilkes University in Pennsylvania were named in his honor.

Cross-eyed with a squint and a jutting lower jaw, Wilkes was not an attractive man. To make matters worse, he began losing his teeth while still young. His enemies, of whom there were many, said his face should not be exposed to pregnant women. However, he had a manly bearing, refined manners and a renowned, razor wit. Political adversary Lord Sandwich once warned that Wilkes would either die by hanging or by the pox, to which Wilkes replied, “That depends, my Lord, on whether I embrace your lordship’s principles or your mistress.” His verbal acrobatics made Wilkes a very successful womanizer, and he claimed it took only “twenty minutes to talk away his face” to a pretty woman.

It is a pleasure to see an author’s talents so perfectly matched to a subject as Cash is to John Wilkes. Cash’s witty writing perfectly complements the life story of one of the most colorful characters in English history. He tells the tale with a surgeon’s skill, resulting in a very precise, well-researched character study.

ALLYSON PATTON

Briefly Noted:

Tudor Knight, by Christopher Gravett, Osprey Publishing, New York, 64 pages, softcover $17.95.

Flodden 1513: Scotland’s Greatest Defeat, by John Sadler, Osprey Publishing, New York, 96 pages, softcover $18.95.

OSPREY PUBLISHING’S ongoing series of monographs in military history are hard to beat. Battles, weapons, warriors and warfare: The Osprey topics are clearly written and superbly illustrated with photos, art and maps. These books are a little pricey for their weight. For those with special interests, though, they are a great treat or a wonderful gift.

London: A Historical Companion, by Kenneth Panton, Tempus Publishing, Stroud, Gloucestershire, 472 pages, softcover $35.

BOOKS ON LONDON could fill a bookshelf of half a furlong. This comprehensive, illustrated gazette of London’s buildings, personalities, institutions and events can replace most of them. From Abbey Road to the Zoological Gardens, Panton’s dictionary format introduces the neighborhoods and delights of London’s 2,000-year history and present world prominence as a center of culture and commerce. You might not have known, for instance, that the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association, founded in 1859, still maintains drinking troughs for animals around London.

Comments