Guy Fawkes: "Remember, remember the Fifth of November."

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 saw a dozen Catholic conspirators attempt to blow up Parliament and King James. It was Guy Fawkes who was found in the basement of Parliament guarding 26 barrels of gunpowder.

Whoosh, bang, aah…! Stars shatter fizz and fade until the next volley of fireworks shoots into the night sky. You could be in any town or city in Britain, hot potato in hand. It’s November 5, and an overstuffed effigy of poor old Guy Fawkes lurches on top of the bonfire, flames gobbling at his toes.

Annual celebrations of Bonfire Night, Guy Fawkes Night, or Fireworks Night, call it what you will, are a great time to join the crowds, to watch parades and pyrotechnics. Yet it’s a torrid mix. Alongside the jollity creep flickering shadows of less-majesty:

Remember, remember the Fifth of November,

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason, why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

The tale we commemorate is well known, how a bunch of Catholic conspirators sought to blow up King James I and Parliament in 1605. Convention says that the group wanted to reestablish the Catholic religion in England. More recently, though, it has been suggested that the plotters were set up, possibly by Government agents, who judged that in the backlash of a failed coup, Protestantism would be reinforced. The truth remains a mystery.

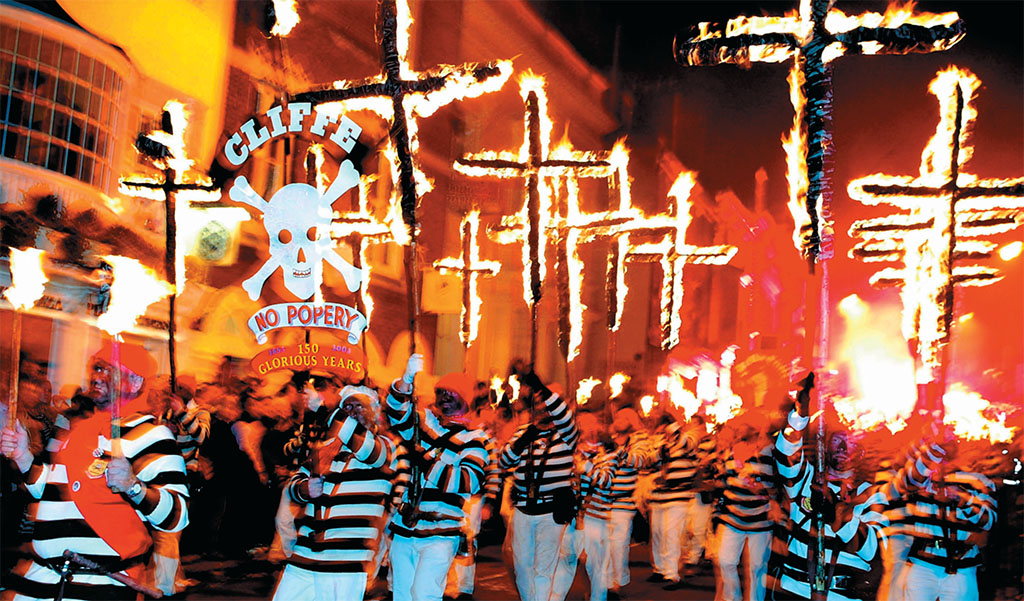

Six different Bonfire Societies parade through the streets of Lewes, East Sussex, in one of England’s most colorful November 5th celebrations.

In any case, a plan developed to get rid of King, Lords and Commons when they gathered for the state opening of Parliament, November 5. The ringleader, charismatic, troublesome Robert Catesby, was joined by four other main conspirators, including Guy Fawkes, a former soldier, and native of York. They contrived to rent a cellar beneath the House of Lords and stashed 26 barrels of gunpowder.

Then, an anonymous letter warning the Catholic Lord Monteagle to stay away from the Opening of Parliament blew the game. Searches of the House of Lords’ basement on November 4 revealed Fawkes and the kegs, and by November 12, most of the conspirators had been killed or taken to the Tower of London. They were tried for high treason, hanged, drawn, and quartered in the bloody fashion of the day.

Parliament, mopping its collective brow, met in January 1606 and passed a Thanksgiving Act, designating November 5 a time for national celebration, with church services and bell ringing to commemorate “the joyful day of deliverance.”

Folk were permitted to light bonfires and make merry, and the act remained in force right up until 1859. After that, church services may have fallen away, but people continued to party.

Over time, celebrations changed. Effigies, of the pope or the Devil, were burned atop the bonfire quite early on, reflecting continuing religious tensions. Domestic political enemies were also symbolically put to the flame. But by the 19th century, following the gradual removal of laws against Catholic worship, Guy Fawkes became the scapegoat. Though he was always a minor player in the plot, Fawkes nevertheless was the one caught red-handed.

Sparklers are one of the joys of any child’s Fireworks Night celebration. “A penny for the Guy?” is the invitation to contribute the funding thereof.

Give an inch and people take a mile, certainly when ale flows. November 5’s orderly processions and controlled bonfires soon gave way to wilder japes: Rolling blazing tar barrels around town, shooting off guns, rollicking and boozing. Soon, respectable 19th-century citizens began to oppose the disruptions and soon fires and fireworks within the confines of towns were banned. Police—even local militia—were drafted to suppress offenders, and not a few towns became the battleground between those who would uphold their customs and those who would reform them.

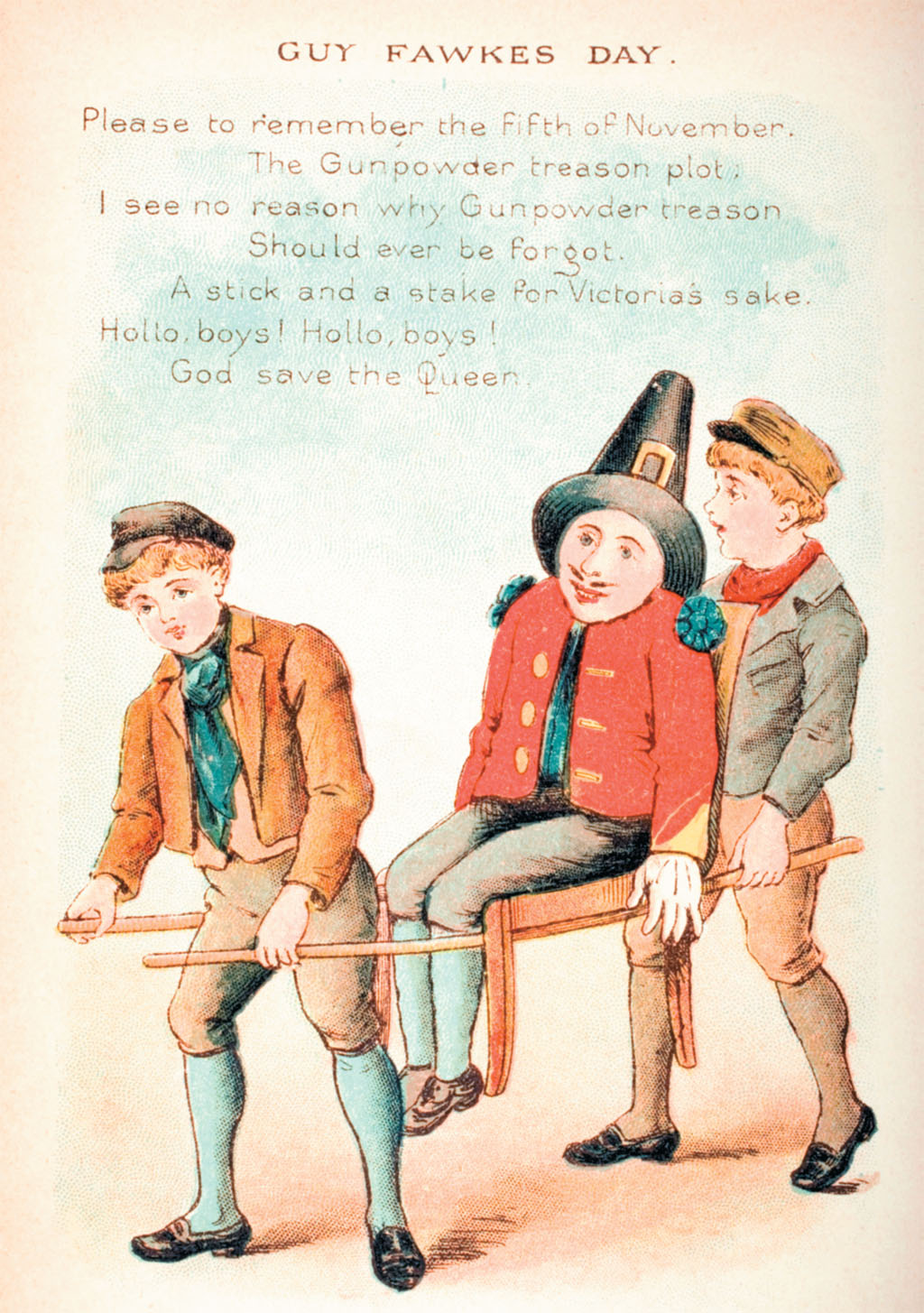

This 1890s lithograph showing two lads carting their effigy of Guy Fawkes toward his inevitable doom on the bonfire illustrated Mother Goose rhymes.

An open field often provided a practical compromise for the madcappery. Or revellers were encouraged to celebrate en famille in back gardens—my own 1960s childhood experience, with over-the-fence frivolity shared with the neighbors.

From the Victorian era and into the 20th century, Bonfire Night also metamorphosed into a children-centric custom. “Penny for the Guy?” became the cry from street corners, where kids stood with their newspaper-stuffed effigies. “Remember, remember…” the chant.

Today the fashion in most cities and towns is for big set-piece public fireworks displays, some choreographed to music, some with funfairs attached, on or close to November 5. They’re ideal for families. Castles like Leeds in Kent make stunning backdrops, too. Or nurse a mulled wine and watch fireworks at a village pub—The Olde Coach House in Ashby St. Ledgers, Northamptonshire, for example. The nearby Manor House was the principal home of the Catesby family, and Robert reputedly held meetings of the conspirators in the half-timbered gatehouse.

Me? I get me hence to the venues where older traditions still flourish, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s hometown, Ottery St. Mary in Devon. Here locals run through the streets lugging flaming tar barrels: Proceedings start with smaller, junior ones in the afternoon and culminate with adults dashing about after nightfall with “the gert big unz”—the carrying of the very largest barrel heralds midnight.

Catch a fire

Even as a spectator you need to be nifty on your feet as sparks fly and crowds follow or flee the runners. The tangled tradition could be rooted in a ritual to rid the streets of evil spirits, but now Guy Fawkes presides, perched on top of a 30-foot bonfire.

Sussex is another favorite hotbed of fiery fun. The town of Battle claims the country’s oldest recorded Bonfire Night—church books of 1686 note the expenditure of 17 shillings and sixpence “at gunpowder treason for rejoicing.”

Gunpowder manufacture was among the town’s trades up to 1874, and even into the 1950s, you could buy the stuff by the pound at the ironmonger’s, to make your own “rousers” or squibs!

Today you’ll have to settle for joining the costumed Battel Bonfire Boyes on their torchlit procession through town—visitors are encouraged to pull on fancy dress. Each year a different effigy, reflecting issues of the moment, is unveiled: Blair and Brown in the Punch and Judy Show (2006); moose-huntin’, hockey-mom Sarah Palin “Too Hot to Handle?” (2008). It’s all in the original, scurrilous spirit of tradition.

Nearby Lewes sees six different Bonfire Societies parade in costume through the streets on November 5, and each has its own bonfire. Protestant martyrs from the reign of Queen Mary (1553-58) are recalled as well as Fawkes in the smoky, fireworks-filled night. The event has become so popular that the town now gently discourages outsiders from attending—but they come anyway.

What would Fawkes, executed when he was 35, make of his notoriety across four centuries? In a 2002 BBC poll to find the 100 Greatest Britons, the public voted him into 30th place, and he is often toasted as “the last man to enter Parliament with honorable intentions.”

To this day the Yeomen of the Guard make a ceremonial search of Westminster Palace just before November’s State Opening in case a Fawkes is lurking. Then the MPs pour in.

Comments