The haunts and trysts of Robert Burns—“the Scot of the Millennium”

[caption id="BrigoDoon_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

CHRIS SHARP

Robert Burns is the central icon of the Scottish Tourist Board’s 2009 Homecoming advertising campaign, designed to encourage Scots and their descendants from all over the world to visit Scotland this year. Burns was the natural choice because the internationally renowned poet and songwriter is universally associated with Scotland. These associations are fervently enhanced in annual Burns’ Night Suppers, celebrations of the poet’s birth every January 25th, which are held wherever Scots live. And the world over, what would New Year celebrations, Clan and Caledonian gatherings be without a poignant rendition of Burns’ “Auld Lang Syne”?

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img1" align="aligncenter" width="139"]

CHRIS SHARP

Burns’ selection, in this the 250th anniversary of his birth, is an ideal opportunity for many to reacquaint themselves with his work and for others to be introduced to the pleasure of reading his verse. His 600-plus poems and songs voicing the universal themes of love, patriotism, work, nature and humanity, though mostly written in Lowland Scots, are accessible to all.

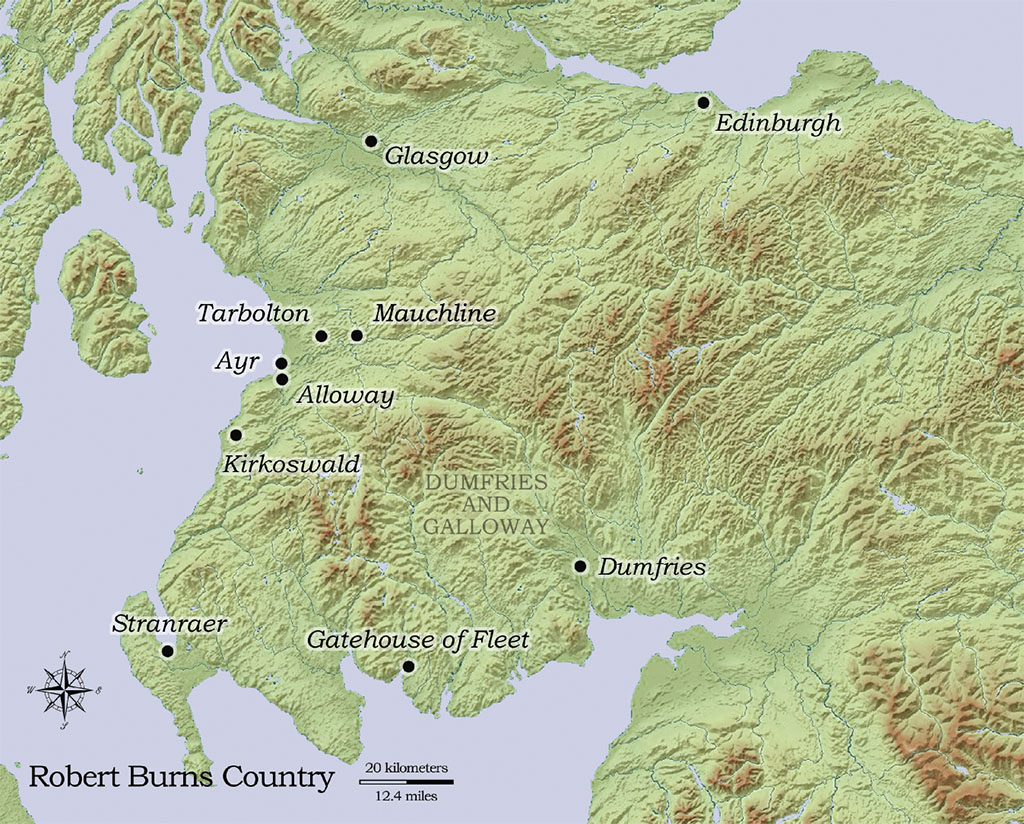

Perhaps the best way to develop an appreciation of his life and legacy is to spend a few days visiting where he lived. Conveniently, Burns spent most of his life in the geographically close counties of Ayrshire, Dumfries and Galloway. Robert Burns was born on January 25, 1759 in Alloway, Ayrshire, the first child of William and Agnes Burnes (Robert changed the spelling). Unsurprisingly his parents, particularly his father, and the contemporary socio-political climate strongly influenced young Robert’s attitudes and poetry.

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

GREGORY PROCHE

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img3" align="aligncenter" width="959"]

CHRIS SHARP

William Burnes was an economic migrant from the Highlands. Like many Highlanders, following Bonnie Prince Charlie’s defeat at Culloden in 1746 and the punitive measures imposed on them, William was forced to leave to seek work elsewhere. Such forced migration from the Highlands created an underlying atmosphere of injustice. Simultaneously throughout the 18th century, following the 1707 Act of Union between Scotland and England, there had been an inexorable imposition of English political, economic and cultural values upon the Scots. This Anglicization of Scotland found little favor in William’s household.

In 1756 William Burnes leased seven and a half acres of land in Alloway, meaning to become a self-supporting tenant farmer. On this land he built an “auld cley biggin,” as Robert referred to the croft where he was born. The cottage still exists and is the centerpiece of the Burns National Heritage Park. This obvious starting point for Burns associated tours also includes the Burns Museum, Alloway Old Kirk, the Burns Monument, the Auld Brig O’Doon and the Tam O’Shanter Experience.

The thatched cottage combines family quarters, livestock stabling and a produce store. The restored building, with period artefacts, gives a good impression of how dark and cramped the quarters were. In the single family room, which was both the kitchen and bedroom too, mannequins in contemporary dress represent the intimacy of the Burnes family life. Robert had a happy childhood here with convivial evenings among relatives and friends, enjoying reading, traditional music and song, and listening to enchanting local tales filled with devils, ghosts, fairies, witches and warlocks. His parents also valued formal education, and with several neighbors they employed a local teacher, John Murdoch, to educate their children.

The museum is a mishmash of memorabilia: first editions, personal items, annotated fragments of poems and numerous letters. Of particular interest are the songs he wrote, collected and then donated copyright free to the Scots Musical Museum. These songs, including “A Red, Red Rose” and “Charlie He’s My Darling,” were written in Scottish dialect and, like his poetry, served to maintain Scottish identity. Ironically, in that he died close to penury, many singers, among them Kenneth McKellor and Carly Simon, have profited hugely from his work.

The Tam O’Shanter Experience is a trinket emporium in whose auditorium there are regular presentations of “Tam O’Shanter,” his epic poem incorporating ghost stories learned at his Alloway hearth. A short walk away, the auld Alloway Kirk “draws nigh, where ghaists and houlets cry,” the imaginary setting for Tam’s encounter with revelling witches and warlocks. The kirkyard is full of gravestones, including those of his parents.

Down the hill from the kirkyard is the Brig O’Doon where Tam fled on his nag Maggie, pursued by the “hellish horde,” knowing from local knowledge that the witches, “dare na cross” a running stream. In the poem’s dramatic climax, as Tam and Maggie cross the bridge, the witch Nan makes a final leap and grabs Maggie’s tail, which fortunately falls off, allowing them to make it safely home. Today, visitors have a calmer crossing over the Brig O’ Doon.

‘HE WAS AN ABLE PLOUGHMAN, EARNING ROBERT BURNS THE SOBRIQUET THE “PLOUGHMAN POET”’

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

CHRIS SHARP

Above the Brig, in an ornamental garden, is the Grecian-styled Burns’ Monument, constructed in 1823, consisting of nine pillars, representing the muses, and a triangular base containing a Statue Room. Here a marble bust of Burns is in the company of life-sized sculptural interpretations of Tam, his friend Souter Johnie and Nansie Tinnock, the landlady of Poosie Nansie’s alehouse in Mauchline. All three sculptures have smiling faces representing Burns’ love of fun and good company.

In 1766 William Burnes moved his family from Alloway to a farm holding at Mont Oliphant. Scottish tenant farming was a grinding business, with landlords constantly raising rents and making often impossible demands for increased yields. Financial problems forced the Burnes family to move to Lochlie and then Mossgiel. The later two farms are near the small towns of Tarbolton and Mauchline. On them, Robert from an early age would have done his share of the laborious farm work. He was an able ploughman, earning him the sobriquet the “ploughman poet.” Each year in Mauchline there is a ploughing contest in honor of his ploughing prowess.

As he ploughed his father’s fields he would have been fully aware of the devastating impact on Scottish society of the iniquitous Highland Clearances. Also the late 18th century was a politically charged period, with egalitarian revolutions in America and France. Certainly the removal of an overbearing foreign power and an antiquated aristocracy found popularity with many Scots, Robert included. Such events may have been discussed at the Tarbolton Bachelor’s Club, a debating society he founded.

Thus Robert, a lively young man and reasonably educated, became politically aware of domestic and international issues concerning justice. Morally, from his father, he had acquired great respect for the church, but he could not abide some of the church elders. Eventually these influences reveal themselves in such poems as “The Ruined Farmer” and “To A Mouse.” The later poem is often derided as a childish trifle, but John Steinbeck, for example, was cognizant of its egalitarian innuendo when he paraphrased the line: “The best laid schemes O’ Mice and Men.”

Many of these poems were written in Mauchline where Burns’ reputation for being a hedonistic, hard-drinking philanderer germinated. Robert was certainly hedonistic, but probably not hard drinking. Also he was charming, good looking and he had more than a roving eye for the lassies.

He was, undoubtedly, a philanderer. His numerous affairs resulted in 14 acknowledged children, trouble with agitated fathers and the Calvinist Kirk. Prominent women of this period in Robert’s life were Elizabeth Paton—mother of his first child; Mary Campbell, poetically referred to as Highland Mary; and Jean Armour, his eventual wife. The rich legacy of this libertine lifestyle is the best of his romantic poetry, a theme explored in Mauchline’s Burns’ House Museum, his and Jean’s former home.

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img5" align="aligncenter" width="502"]

CHRIS SHARP

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img6" align="aligncenter" width="502"]

CHRIS SHARP

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

CHRIS SHARP

Not surprisingly, around Mauchline there are several places associated with Robert—a leaflet listing them is available from the Museum. In Mauchline Kirkyard, scene of “The Holy Fair,” are several graves of Burns’ influential peers including Gavin Hamilton, a friend and lawyer who encouraged Robert’s writing. The church, much altered since Robert’s time, was where he, Gavin and Jean had to sit in the “creepie stall” and recant their sins of fornication. Robert was incensed by this Calvinist court’s cant and hypocrisy as revealed in his witty and satirical “Address To The Unco Guid” and in “Holy Willie’s Prayer.”

Opposite the Kirkyard is Poosie Nansie’s alehouse, a favourite location for Robert’s merrymaking, recalled in “The Jolly Beggars.” Nearby in Kirkoswald is Souter Johnie’s Cottage, home of Robert’s blacksmith friend John Davidson. This museum presents the comfortable lifestyle that was attainable by established 18th-century tradesmen.

Before marrying Jean, Burns had made plans to emigrate to Jamaica with Mary Campbell. To raise funds for this venture he was encouraged by Gavin Hamilton to publish his first book of poems: Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect. This is known as the Kilmarnock Edition and received great critical acclaim and financial reward. With fame and fortune beckoning, Robert jilted Mary, who died shortly after in childbirth, and returned to Jean Armour, who was pregnant again, in Mauchline.

Much to see in Burns’ Country

Alloway is easily reached by public transport from Ayr which has regular bus and train connections to Glasgow. Renting a car makes it easier to visit all the places mentioned in the article. Certainly Tarbolton, Kirkoswald, Mauchline are difficult to reach by public transport. Alloway is just over an hour by car from Glasgow Airport.

The Burns Cottage and Museum in Alloway are part of the Burns National Heritage Park. They have several leaflets about visiting places associated with Burns. The two most useful ones are: “Discover Burns in Scotland” and “The Burns Heritage Trail.” The following web sites are of some use in planning a trip: www.burnsscotland.com;

www.burnsheritagepark.com; www.ellislandfarm.co.uk; and www.mauchlineburnsclub.com.

Several of the attractions have varied, irregular opening times, particularly the Tarbolton Bachelors Club and Souter Johnie’s Cottage; therefore it is best to check before departing. The Burns Cottage and Museum staff can advise.

Accommodation: In Alloway, there is the Brig O’Doon Hotel [email protected].

Further accommodation suggestions for the area can be found at www.visitscotland.com.

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img8" align="alignleft" width="659"]

CHRIS SHARP

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img9" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

CHRIS SHARP

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img10" align="aligncenter" width="739"]

CHRIS SHARP

[caption id="BrigoDoon_img11" align="aligncenter" width="412"]

CHRIS SHARP

Robert spent much of 1787 in Edinburgh where the literati of the day encouraged the “heaven taught ploughman” to write his verse in English. Robert refused to bow to this vogue for the Anglicization of Scottish language. By this patriotic refusal Robert has done much for the conservation and encouragement of Scottish culture, and it is this legacy which probably contributed to his recognition by Scots in 2000 as “the Scot of the Millennium.”

In 1788 Robert became the tenant of Ellisland Farm beside the River Nith outside Dumfries. As a working farm it was an economic disaster, which is why it is known as the Poet’s Farm. Today the farm has an apt collection of ploughs and the visitor can walk by the river where Robert ambled while composing his verse. Unfortunately, income from the farm and poetry were inadequate so Robert obtained employment with the local Excise. This exhausting job, riding all over Dumfriesshire, in both foul and fair weather, collecting taxes from local people, caused his health to deteriorate, and the family to move into Dumfries in 1791.

‘HIS NOTION OF INTERNATIONAL FRATERNITY STILL RESONATES TODAY AND CONTINUES TO ATTRACT MANY TO HIS POETRY’

From the Robert Burns House there are several short walks that explore Robert’s Dumfries. All are pleasant and can be completed in a morning. You can visit the Burns Statue, the Theatre Royal, the Robert Burns Centre and, unsurprisingly, an alehouse or two: The Hole in the Wa’ and The Globe. The latter offers fulsome meals—perhaps the place to personally Address the Haggis—and tasty ales. Here in its cozy bars, with low ceilings and uneven floors, it is not difficult to imagine Robert conversing with friends or interesting visitors.

By now patriotic, Robert was attracted to France’s revolutionary political ideology and the concepts of equality espoused in Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man. This was potentially dangerous for a government employee, as Britain was at war with France and the possession of Paine’s book was considered seditious. Robert hid his contempt for the London government and showed his admiration for equality of rights in the verse of two poems: “Robert Bruce’s March to Bannockburn” better known by its opening line: “Scots, wha hae wi’ Wallace bled”; and “A Man’s a Man for A’ That.” The final lines in the latter poem, “It’s comin yet for a’ that/That Man to Man the warld O’er/Shall brothers be for a’ that,” summarises his notion of international fraternity that still resonates today and continues to attract many to his poetry.

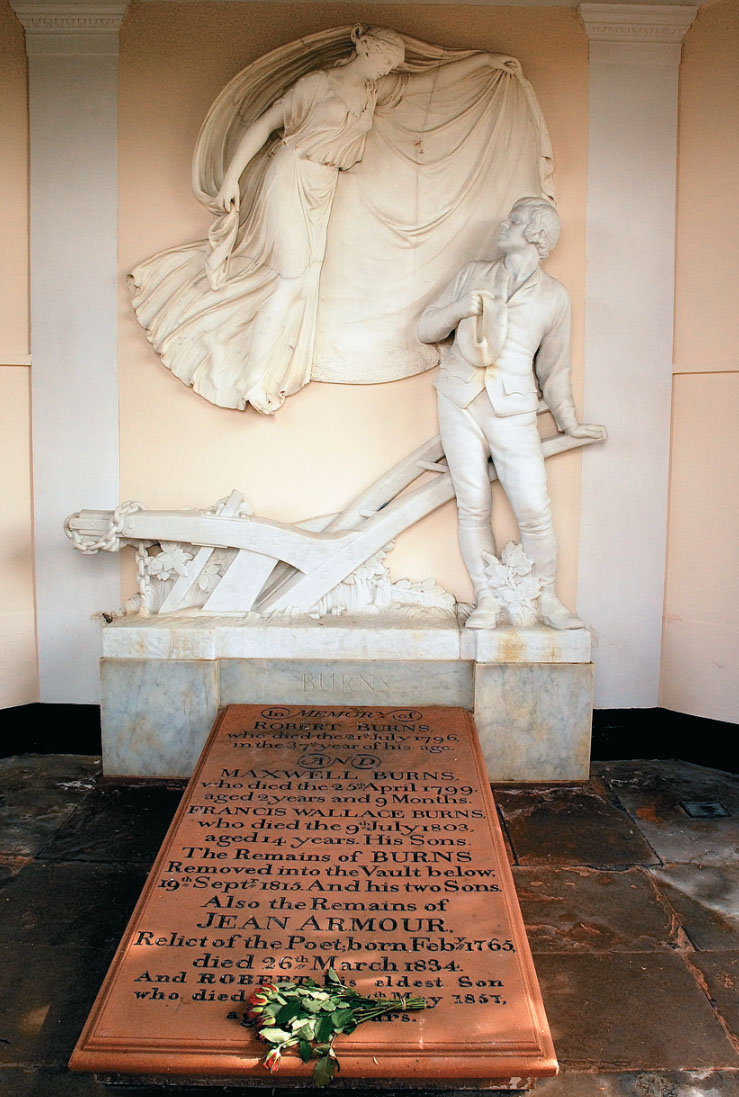

During 1795 Robert became increasingly unwell and also suffered increasing financial problems. In July 1796, upon doctor’s advice, he went to Brow and took a chilling dip in its well, the coup de grace to his weak health. He died a few days later. His funeral was attended by thousands. In 1817 his body was moved to the Burns Mausoleum in St. Michael’s Churchyard, Dumfries. On the approach to the church from the Burns Museum there is a statue to Jean Armour, so easily dismissed as his slighted wife. As compensation, among all Robert’s verses she knew these words to be true: “Beyond the Sea, beyond the sun/Till my last weary sand was run/Till then – and then – I’d love thee” and that she was, “The lassie I lO’e best.”

The Grecian mausoleum is approached through a jumbled graveyard. In the simple mausoleum, above Burns’ tombstone, is a basrelief showing Robert with a plough below the cloak of a poetic Muse. But, unobserved by many, in the shadow of the plough shear is a tiny mouse, a fitting epitaph to a man whose poetry covered themes both great and small.

Comments