[caption id="BritainsHistoryinaNewNationalMuseum_img1" align="aligncenter" width="261"]

IN THE MIDST OF BRITAIN’S NATIONAL DISCUSSION of how to preserve and promote its identity, which I’ve alluded to before, former Education Secretary Lord Baker has suggested that a new institution is needed to promote a true sense of national pride. He proposes a National Museum of British History. While a single institution, however magnificent in scope, will hardly in itself dissolve the social miasma that floats in the currents of Britain these days, Lord Baker’s idea seems self-evident.

After all, as we Anglophiles know, what a history Britain has to celebrate! And while many nations have national history museums, including the United States, Britain does not. London is certainly graced with a more than generous share of world-class museums, of course, but none is devoted to either English or British history. The British Museum, ironically, is the repository of what they brought back from everywhere else in the world.

As it happens, Lord Baker’s idea has been quickly and enthusiastically embraced by Prime Minister Gordon Brown and by a host of public figures ranging from Dame Vera Lynn to Sir Richard Branson. The PM himself delivered a lengthy statement of support, encouraging, “And as we take forward our discussions, we will focus not just on how a museum could relate the narrative of British history, but how it could celebrate the great British values on which our culture, politics and society have been shaped.”

‘What a history Britain has to celebrate! Yet Britain does not have a museum devoted to that history’

This sounds wonderful, and I am happy to join what I hope will be a swelling bandwagon of support for the idea. On its Web site, the Daily Telegraph has been hosting a forum on what might be included in the new museum to represent British history and reinforce the cultural values that have defined Britain. As you might imagine, the forum has received a plethora of suggestions, both serious and not so. It has also revealed what will be the great challenges to such a mammoth and worthy undertaking.

For instance, it did not take long for folks to point out that Britain as a nation-state has only existed since 1707. Both Wales and Scotland, for instance, have their own national history museums already, in Cardiff and Edinburgh respectively. Will a new National Museum of British History deal only with the last 300 years? Or will it be largely a museum of English history, with Scotland and Wales cast in a supporting role?

Then there’s the matter of the collection. What localities, museums, foundations and organizations around the country are going to want to surrender their prize attractions to be gathered in a single place at their expense? Somehow it is hard to see Salisbury Cathedral donating its copy of the Magna Carta or the Scottish Parliament sending the Stone of Destiny south again. I don’t think Llangollen will crate up the Pillar of Eliseg or Bristol surrender the SS Great Britain. It’s going to be a challenge.

IN TERMS OF BRITAIN’S great national store of historical artifacts and archives, the collection of a new national museum may come down to whatever the acquiring curators can beg, borrow and steal. The temptation, of course, will be to re-create what is deemed to be important but cannot be acquired. We could end up with a plasticene Stonehenge and a photocopied Magna Carta. What about a virtual reality Battle of Hastings and holograms of HMS Victory?

The truth is that Britain already has a national history museum. The challenge is that its fascinating exhibits and interactive displays are scattered across the island from Land’s End to the Shetlands.

Before a new National Museum of British History becomes a reality, of course, there are also such practical details as location and funding. It will take years of planning, public debate and wrangling before such an ambitious undertaking could open its doors and serve its major public purpose. In the meantime, however, we just have to go see Britain’s national history in situ for ourselves.

Here is what visits might get my own personal collection started to represent Britain’s history over the centuries.

[caption id="BritainsHistoryinaNewNationalMuseum_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

TIM GRAHAM/GETTY IMAGES

Really ancient history, of course, we do not know much about at all. It can be symbolized, though, by the some 600 stone circles and henges found across Britain, from the Merrie Maidens down near Penzance to the Standing Stones of Calinish. Most famous and most visited, without doubt, are Stonehenge and Avebury. My own favorite, however, is Castlerigg Stone Circle, high in the Lake District above Keswick. The views across the fells are magnificent. Whatever those protoBrits were doing there 5,000 years ago, they chose an awe-inspiring location.

[caption id="BritainsHistoryinaNewNationalMuseum_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©TRAVEL AND PLACES/ALAMY

Moving right along, Butser Ancient Farm on the south downs of Hampshire just above Portsmouth is a most remarkable site, re-creating with extraordinary attention to accuracy the structures and lifestyle of a prosperous pre-Roman Celtic farmstead. The huge Celtic Great House may look primitive compared to modern architecture, but it was a highly sophisticated piece of engineering, built to last 200 years. Visitors to Butser will never look at the Celts the same way again.

Roman Britain? Folks who pay scant attention to such things would be amazed at the sheer number of “high quality” historic Roman sites there actually are in Britain. Colchester to Chester, Dorchester to Doncaster: everywhere with caster or chester in the name used to be a Roman fort. Roman villas, amphitheaters, walls, roads and castles abound. Bath is England’s most popular Roman site, and justly deserves its tourist reputation and its crowds. Roman Britain wasn’t all baths and skittles, however. Up near the Northumbrian market town of Hexham, at the Roman fort of Housesteads , you can walk up across the windswept, barren moors to desolate Hadrian’s Wall. Lonely, cold Roman soldiers manned that mammoth barrier for centuries.

After the Romans withdrew, Britain fell into what we call the Dark Ages. These were the days of the historic King Arthur, attempting to forestall for Celtic Britain the gradual but steady immigration of Germanic tribes. Jim Hargan tells the story well in this very issue. A host of legendary Arthurian sites evoke the era. I have long concluded that the old Roman city of Viroconium is the likely site of the historic Arthur’s capital, but it is hard to beat Somerset’s Glastonbury Abbey for the sheer romance of the era.

Just as the Saxons had settled into England, they faced a couple of centuries’ worth of Viking botherance. History’s man was King Alfred of Wessex, who unified those little Saxon kingdoms into England and more. Alfred the Great’s his spirit lives on in Winchester, where his statue, sword drawn, presides over the pretty High Street of the ancient capital of Saxon England.

Then, along came the Normans. Battle Abbey in Battle, six miles north of Hastings on the East Sussex coast, marks the site of the battle itself. After William the Conqueror went on to carve up the country with a few hundred knights, he kept busy starting projects such as Windsor Castle and the Tower of London. Just for a place to relax, William created the Nova Foresta in 1079, a 140,000-acre hunting preserve along the south coast of Hampshire. His son didn’t keep up the good work, however, and while hunting in the New Forest got himself carelessly shot with an arrow. This Norman low point is marked by the Rufus Stone near Cadnam—ironically not far from Winchester.

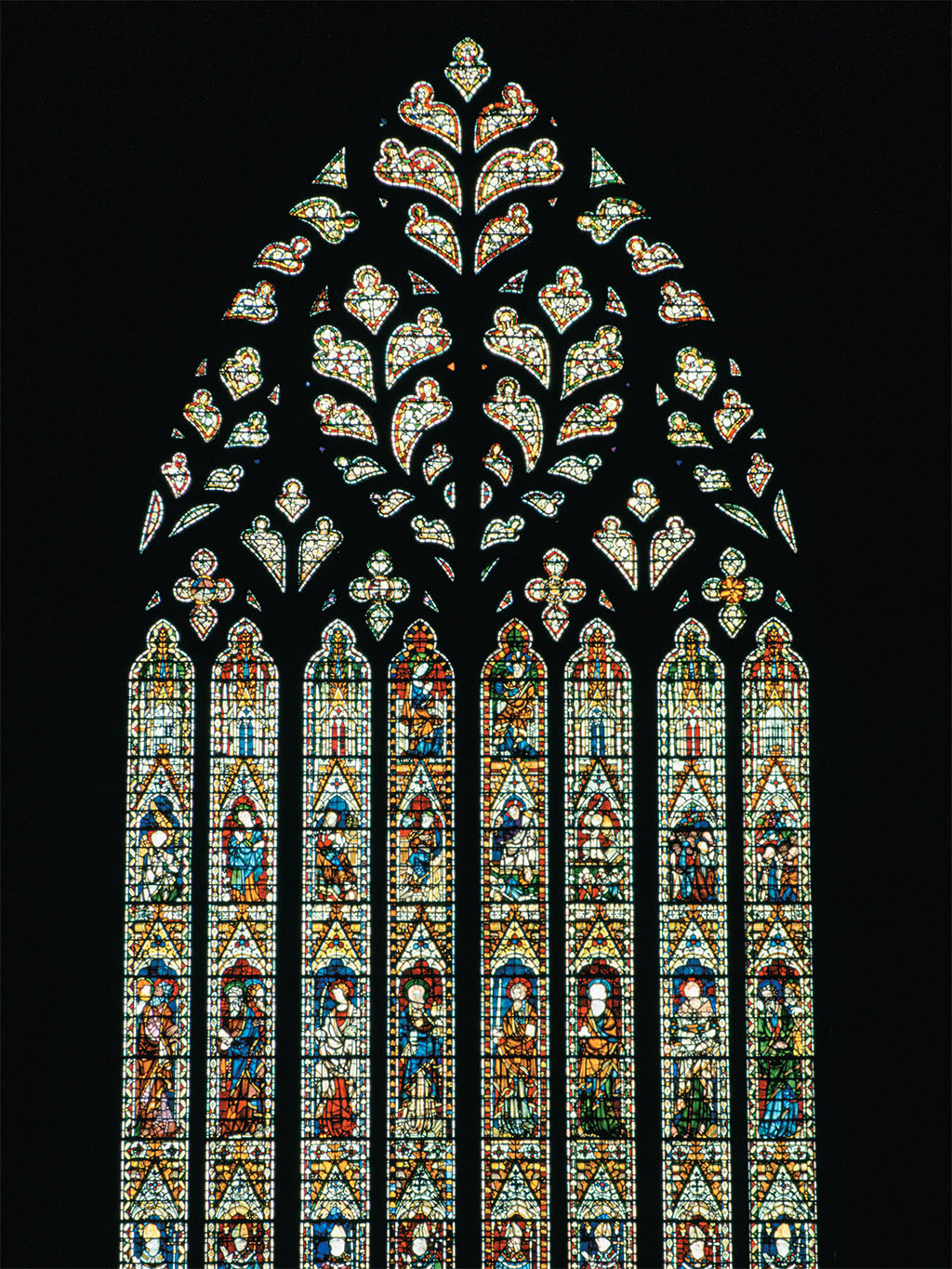

THE PLANTAGENET DYNASTY reigned in England for 300 years. How medieval. The feudal institutions of church and state are dramatically represented in our traveling museum of history by cathedrals and castles, still standing after an octet of centuries. To a populace that lived in thatched huts with dirt floors, the sheer size and substance of those edifices communicated the overwhelming power that came with authority over their lives. Those Edwardian castles such as Conwy and Caernarfon that Jim Hargan wrote about in our last issue are as good an example as you can visit. Cathedrals from Exeter to Durham tell an equally important other half of the tale. York Minster may be my favorite, with its unequalled munificence of medieval stained glass. Besides, it reposes in the unequalled surroundings of medieval York.

Oh yes, and along the way, there was the pesky Black Death, the Magna Carta was signed, the monarchy limited and the roots of Parliament established. Those Middle Ages ended, of course, at the Battle of Bosworth Field.

There are actually few English battlefields that do justice to themselves as a destination visit. Perhaps the best, however, is Bosworth Field, about 10 miles west of Leicester. At the visitors center, you can see from good vantage how the battle unfolded and walk the marked lines where the last English king to lead soldiers in combat lost his kingdom and his life to the upstart Henry Tudor.

‘Along the way there was the pesky Black Death, the Magna Carta was signed and the monarchy limited’

After Richard III’s summary dispatch at Bosworth, we enter the Renaissance, and the tumult of the Tudors. If the Plantagenets built castles, the Tudors built palaces. It would be hard to find a better example of what they thought of themselves than Hampton Court Palace. The interest in art, music and literature that characterized the age is celebrated still in William Shakespeare. That Tudor tumult, of course, was the Reformation. Meanwhile, up in Scotland….

Just telling the story thus far illustrates what a mammoth task lies ahead in defining and illustrating the history of Britain in the parameters of a single national museum. Already, ardent British Heritage readers are arguing, “But what of this, or what of that?”

Here is an opportunity for Britain to define its identity in both concrete and symbolic terms. It is indeed a complex matter, fraught with the temptations of political correctness and historical revisionism. We are, as human beings, so inclined to remember the good and let the bad fade from our individual and corporate memories. National pride is vindicated far more by celebrating the Tudor munificence of Hampton Court Palace than by gazing on the Martyr’s Memorial in Bury St. Edmond’s churchyard.

What is far more likely, of course, is that our squishy modern political correctness will direct too much navel gazing. It doesn’t take too close an inspection of any time past to realize there is no past to which a reasonable person today would prefer to return. Britain and her communities, like the entire rest of the First World, take far too for granted the blessings that our evolved democracy, personal freedoms and economic liberty have engendered for our lives at the start of the 21st century.

So, I invite you to enter the dialogue. What should go in a new National Museum of British History? How should the island present its more than 2,000 years of history in such a way that it displays and reinforces the British identity and values of today? Write us a note or send an e-mail to [email protected]. Next, we’ll take to the road again on the national history trail.

[caption id="BritainsHistoryinaNewNationalMuseum_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©HORIZON INTERNATIONAL IMAGES LIMITED

Comments