Britain’s most famous locomotive and the world’s first fatal railway accident

[caption id="BritainsMostFamousLocomotiveandtheWorldsFirstFatalRailwayAccident_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="BritainsMostFamousLocomotiveandtheWorldsFirstFatalRailwayAccident_img2" align="aligncenter" width="538"]

A MARK OF PERSONAL RESPECT and affection has been placed here to mark the spot where … The Right Hon. William Huskisson M.P. singled out by an inscrutable Providence … met with the accident that occasioned his death …which changed a moment of noblest exultation … into one of desolation and mourning.

—From a memorial at the accident site

The MP for Liverpool and the Duke of Wellington didn’t see eye to eye, and everyone knew it. But the morning of September 15, 1830, did not seem the time for political squabbles. Rather, this was a time for joyful exuberance celebrating the opening of the new Liverpool and Manchester Railroad.

A bit over 170 years later, it is hard to appreciate just how auspicious the occasion seemed. At the time, rail travel was still a novelty—a technology that caught people’s interest in the same way space travel would several generations later. In fact, the Liverpool and Manchester became, on that fateful morning, the first 14 intercity railway in the world to employ steam-powered locomotives to haul both passengers and freight. The locomotive that had been handpicked for that task, the “Rocket,” had already earned fame to rival that of the visiting prime minister.

In addition to the duke and the MP, crowds of enthusiastic well-wishers turned out. When the carriage in which the official visitors rode, pulled by the locomotive “Northumbrian,” stopped at Parkside station to take on water, some of the passengers disembarked to stretch their legs. While they did so, the duke’s private carriage waited on the southbound track so the public could view it up close. William Huskisson, the MP for Liverpool, meanwhile spotted the duke extending his hand. The two men were sharply divided over both domestic and foreign policy, but the duke’s gesture was encouraging. Perhaps, caught up in the upbeat mood of the day, he intended it as a sign of reconciliation. Huskisson walked over and greeted the duke, standing by the northbound track as he did so.

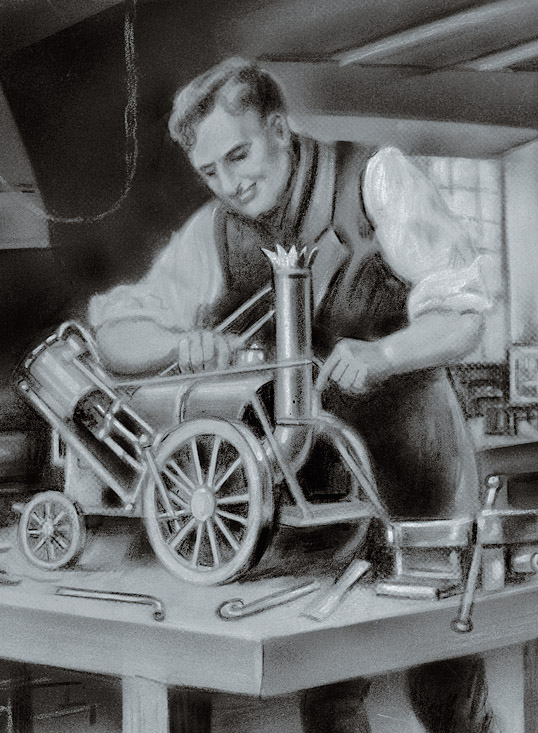

At that moment, shouts alerted Huskisson that the Rocket was approaching on the northbound track. The Rocket owed its fame to the exciting Rainhill Trials, staged just the year before, when the railway’s directors had been searching for the best locomotive to serve their line. “The great rail-road between Liverpool and Manchester now being nearly completed,” the editors of Mechanics Magazine had announced, the railway directors “would give a premium of £500 for the locomotive engine, which should, at a public trial to be made on [October 6] draw on the railway a given weight with the greatest speed at the least expense. The offer, and the brilliant professional prospects which the winning of it presented to mechanical men, naturally exerted a very high spirit of competition among them.”

Prior to this announcement, many experts had advised using proven technology, such as horse-drawn carriages, or engines fixed in place along the trackside that would pull the carriages forward by rope. But notice of the competition at Rainhill, as Mechanics Magazine noted, galvanized some of Britain’s best engineers to action, and no less than 10 designers took up the challenge. Only five of the competitors managed to build their locomotives in time to participate.

The five entrants at the Rainhill Trials were the “Perseverance,” built by a Mr. Burstall of Edinburgh; the “Cycloped,” designed by Mr. Brandreth of Liverpool; the “Sans Pareil” of Timothy Hackwork, Darlington; the “Novelty,” built by Messrs Braithwaite and Erickson of London; and Robert Stephenson’s the Rocket.

The list of designers, in light of subsequent events, is enough to provoke suspicion among conspiracy theorists. Robert Stephenson was, Mechanics Magazine noted, “the son, we believe, of Mr. George Stephenson, the engineer of the [Liverpool and Manchester] railway.” George was also co-founder of Robert Stephenson & Co., which had built the locomotive. In addition to designing its own locomotives, the company had become a supplier for other engineering firms. Among its customers were the builders of the Sans Pareil, who counted on Stephenson to provide the steam cylinders used on their own entry in the Rainhill Trials. Somewhat suspiciously, one of those cylinders failed during the trials, forcing the Sans Pareil to drop out of the contest.

In reporting on the trials, Mechanics Magazine seemed enamoured with the Novelty, less so with the Sans Pareil, and unimpressed with the Rocket, which it admitted was powerful, but judged too large and unstable, and not very fuel-efficient. The remaining two designs proved unreliable and quickly dropped out of the competition.

In the end, in fact, the Rocket won the competition primarily through a process of mechanical elimination, as one by one all of its competitors broke down. Whether through simple luck, sabotage or a fundamentally sound design, the Rocket proved the only locomotive able to finish the trials. A correspondent wrote: “The prize had been at length awarded … to Mr. Stephenson. The directors had no alternative, since ‘The Rocket’ was the only engine which fulfilled the conditions of the competition. There are people here, however, who think that the interests of the public would have been quite as well served, had the directors offered the premium on a more general view of the matter, and conferred it upon that engine which is, upon the whole, ‘the most improved.’”

Of course, it could have been little comfort to Huskisson to know that the locomotive bearing down on him on September 15 the next year, if not necessarily “the most improved,” had a reputation for reliability as well as for speed. Shouts that the locomotive was approaching prompted one of Huskisson’s companions to scramble inside the duke’s coach, and a Mr. William Holmes cleverly positioned himself in the narrow gap between the two trains so that the Rocket would miss him by inches as it passed by. Huskisson, however, seemed befuddled by all the excitement. He tried to climb into the prime minister’s coach, but his hand slipped off the railing, and he stumbled backward. He fell with his left leg lying across the northbound tracks, and as the horrified crowd looked on, the Rocket rolled over it.

A newspaper account records the result: “Huskisson’s injury was severe and although Doctor Brandreth and surgeon Hensman were among the guests, the trackside was no place to attend an injured man. A tourniquet was applied to stem the bleeding, attempts made to console the distraught Mrs. Huskisson, and the MP placed upon a board and lifted to the low car used by the musicians. An engine was dispatched to Manchester to summon further assistance and ‘Northumbrian’ used to take the injured man to the home of the Rev. Mr. Blackburne, the vicar of Eccles. Apart from attempts to ease the pain and to comfort the unfortunate gentleman, little could be done and, after the administration of the sacrament, he expired later in the day at the Eccles’parsonage.

“Naturally, this tragedy cast a cloud over the whole proceedings and, after discussing the matter with Sir Robert Peel, the Duke wanted to cancel the remainder of the programme. The directors, on the other hand, felt that they had a commitment to the public in general and to their supporters in particular. The civic representatives of Manchester and Salford feared unrest at the end of the line if the vast crowds which lined the route for eight miles into Manchester were disappointed, and eventually the cavalcade resumed ….“

In railroading as in theatre, it seems, the show must go on.

Comments