Exploring 4,000 years of history across one of Britain’s most iconic landscapes

Everyone knows the Cotswolds, its dramatic escarpment, hills and hidden valleys dancing between the World Heritage City of Bath in the south and Shakespeare’s Stratford-upon-Avon in the north. Quintessential rural England at its most picturesque, market towns and villages sprung organically from the limestone landscape; churches, manor houses, mills and weavers’ cottages built by a wool trade that defined the region from the Middle Ages.

Even today, some 85 percent of the Cotswolds is farmland of differing hues, while tourism adds £1 billion each year to local coffers.

“Wool churches” like Burford, Chipping Campden and Cirencester, honeypot towns like Broadway, Painswick and Bourton-on-the-Water all draw the crowds. But there’s also 6,000 years of human settlement to explore to genuinely get under the skin of the Cotswolds.

The area boasts a remarkable number of surviving Neolithic monuments – the local limestone provided superb supplies for building – and it claims one of the densest concentrations of Roman villas in the country. Through the ages, royalty have capitalized on the Cotswolds’ strategic location and beauty, whether Saxon King Offa with his seat at Winchcombe or, today, Princess Anne and Prince Charles living respectively at Gatcombe Park and Highgrove.

When the wool trade declined and the Industrial Revolution happened elsewhere, the Cotswolds got stuck in its past; that proved its salvation when Arts and Crafts folk keen on the vernacular “rediscovered” its untouched charms. Motor-car-driving visitors then put it on the tourism map.

Here’s a chronological pick of the places to explore the Cotswolds’ timeline beyond its more familiar wool heritage.

ATimelineofCotswoldTreasures_img1

Rollright Stones, near Chipping Norton

Stonehenge in Wiltshire may grab the prehistoric headlines with its vast monoliths, but the Neolithic/Bronze Age Rollright Stones in open fields near Chipping Norton captivate on a more intimate, human scale.

Comprising three monuments–the King’s Men stone circle, the Whispering Knights burial chamber, and the hunchbacked King Stone guarding a Bronze Age cemetery–the Rollrights range in date from circa 3,500 to 1,500 BC. The Knights and King are railed off, but you can walk right in among the King’s Men, whose pitted faces sprout lichen that’s 400 to 800 years old.

Unlike the builders of Stonehenge, who dragged their bluestones from Wales, the brains behind the Rollrights gathered limestone boulders close to hand. The King’s Men circle, nearly 100 feet in diameter, once mustered 105 stones; now there are 70-odd–legend says they are uncountable. An astronomical alignment is claimed and the local stargazing society even meets here, though that’s more because the site is free of light pollution.

Alternatively, it’s said the Rollrights are a monarch and his army turned to stone by a witch after the old hag tricked the king in a wager to become ruler of all England.

Visiting: 3 miles northwest of the market town of Chipping Norton, signposted off the A44 or A3400 on the Oxfordshire/Warwickshire border.

Chedworth Roman Villa, Yanworth

It’s surprising what you can find when hunting for rabbits with ferrets. A Victorian gamekeeper at Yanworth unearthed pieces of colored stone and, with further digging one of the largest Romano-British villas in the country came to light.

The Romans arrived in the Cotswolds following the invasion of AD 43, thrived on farming and built fine villas: Chedworth is a favorite, along the Fosse Way (modern day A429) from Corinium (Cirencester), formerly the second largest city in Roman Britain.

ATimelineofCotswoldTreasures_img2

In its 4th-century heyday, this villa in the lovely Coln Valley was home to some of the richest folk in the land, and they enjoyed all the mod cons: underfloor heating, flushing latrines, sauna and steam baths. A suspended walkway allows you to have a good nose over floor mosaics and you can just imagine a proud host showing them off to dinner guests before serving Roman snails fattened on herbs and milk; now a protected species, the snails still live here.

Summer excavations continue to unearth artifacts and the museum, an attractive if incongruous Victorian apparition plonked amid Roman remains, is a delightful little trove of jewellery, figurines and portable altars.

Visiting: 10 miles north of Cirencester; follow brown signs to “Roman Villa” from the A429/Fosse Way; from Cheltenham: A40 and A429.

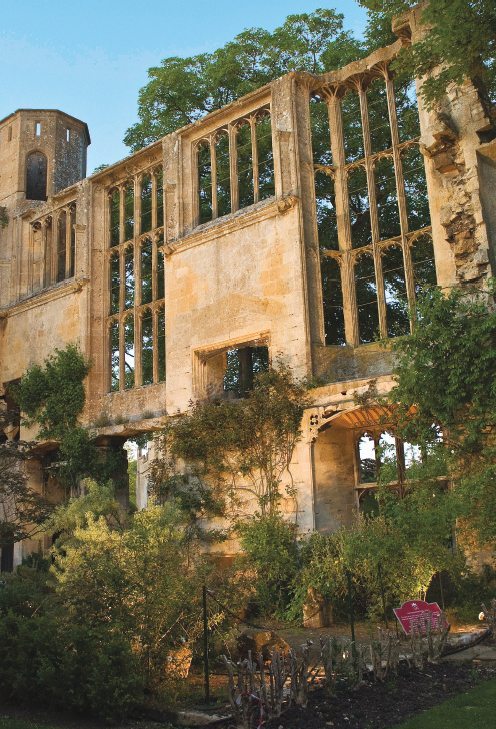

Sudeley Castle, near Winchcombe

Sudeley Castle, glowing gold in a fold of green hills, wraps up Cotswold tales of royalty, romance, ruin and rescue all in one visit.

The chief draw is Katherine Parr and the castle’s Tudor glory days when charming but ruthless Sir Thomas Seymour owned the pile. Katherine, having previously renounced her passion for Seymour to dutifully become Henry VIII’s sixth wife, leapt at the chance to marry Sir Thomas when the king died in 1547–you’ll find her love letter and handwritten books in the splendid red-and-gold Tudor Document Room.

ATimelineofCotswoldTreasures_img3

Tragically, within months of creating a dazzling “second court” at Sudeley, Katherine died following childbirth; she is entombed in St. Mary’s Church in the garden, the only English queen to be buried within the grounds of a private castle.

Sudeley’s award-winning gardens channel Tudor motifs and The Queens’ Garden, named for Katherine, Anne Boleyn, Lady Jane Grey and Elizabeth I, who all walked here, is a stunner for roses in June.

That’s just scratching the surface. Sudeley mines more than 1,000 years of history, tracing connections from Saxon King Ethelred (The Unready) and his daughter Goda, via Richard III; Charles I and ruin following the Civil War; Victorian restoration and modern renaissance under the current chatelaine, Lady Ashcombe, and her family.

Visiting: near Winchcombe, 8 miles northeast of Cheltenham on the B4632.

Westonbirt, The National Arboretum, Tetbury

It’s easy to get light-headed with senses overload at Westonbirt, exploring 17 miles of paths through 600 acres and 15,000 trees clad in exotic foliage (British fighter ’planes were hidden here during World War II and you half expect to stumble on one left behind).

ATimelineofCotswoldTreasures_img4

The National Arboretum is among the world’s finest arboreal collections with some 2,500 different species from Britain, China, Japan, Chile, North America and other temperate climates. It also bears testament to landowner Robert Holford (1808–1892) and his family, who, combining the Victorian passion for financing global plant hunting expeditions with the vogue for Picturesque landscapes, created a magnificent canvas of color interwoven with avenues.

Best time to come leaf peeping is autumn, when caramel scents of Katsura get juices flowing and (helpfully mapped) seasonal trails dive through radiant red Japanese maples and golden beech. Spring, too, is spectacular, from rhododendrons to woodland wildflowers and those scene-stealing Japanese maples getting on their fresh garb.

Also look out for the remarkable ring of 80-plus stumps that forms Westonbirt’s famous 2,000-year-old small-leaved lime. It was coppiced in 2012 so currently seems more like clumpy bushes, but the tree sculpture towering beside it, made from cut lime stems, adds curiosity.

Visiting: approx 3 miles southwest from Tetbury on the A433; follow brown visitor attraction signs from the M4 and M5 motorways.

Kelmscott Manor, Kelmscott, near Lechlade

Father of the Arts & Crafts movement, William Morris (1834–1896), described Kelmscott Manor as a “door to the imagination.” Pushing it open gives a very personal insight into his being and beliefs.

[caption id="attachment_13698688" align="alignleft" width="300"]

By Boerkevitz at the English language Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16575804

From 1871 this 17th-century farmstead on the Oxfordshire Thames became a summer retreat away from London’s bustle for Morris, his family and friends, as they blazed a trail to the Cotswolds that creatives follow to this day.

Seemingly “grown up out of the soil” in harmony with its surroundings, the manor embodies Arts and Crafts ideals of honest, vernacular craftsmanship; gardens and countryside gave Morris nature-inspired designs for his textiles and wallpapers (Willow Bough, Strawberry Thief) that breathed fresh air into stuffy Victorian parlors.

Morris’s famous dictum, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” saw him become mind-bogglingly prolific and Kelmscott’s rooms are an intrigue of possessions and furnishings, including art by his Pre-Raphaelite pal Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who for a while shared the manor’s tenancy–and Morris’s wife and muse, Jane.

Indulge in a little lawn croquet and cream tea, then wander the village to 12th-century St. George’s Church where Morris is buried. There’s the 17th-century Plough Inn with rooms, if you decide to stay.

Visiting: 3 miles from Lechlade (on B449); signposted from both the A417 and A4095.

The Royal Gardens at Highgrove

Prince Charles’ and Camilla’s private gardens around their Georgian family home make a unique finale to our trot through time. The tree house where William and Harry played as children has been renovated for Prince George, and grandpa and grandson have already planted a balsam poplar together. No doubt it’s hoped the Prince of Wales’ renowned green-fingered genes have transmitted.

Charles says, “A garden is a reflection of a person’s soul," and since 1980 he has worked with nature, championing organic and sustainable principles (once considered cranky, now mainstream), to create a series of diverse, interlinking areas.

There’s his iconic Wild Flower Meadow inspired by an urge to save declining native flora, the oh-so-English Cottage Garden, The Sanctuary for peaceful contemplation and The Stumpery, where insects thrive in tree stumps and temples leap up to surprise you. The Kitchen Garden grows favorite royal veg (spring cabbage to Charlotte potatoes) and clipped yews shape-shift along The Thyme Walk.

Tours with one of HRH’s expert guides need to be pre-booked (the gardens open on selected dates, spring to autumn, and are very popular so be quick). The Orchard Restaurant is scrumptious and the shop stocks all sorts of garden paraphernalia and souvenirs, as does the Highgrove shop in Tetbury.

Visiting: at Doughton, approx 1.5 miles southwest of Tetbury along the A433.

Online Extras: While visiting, don't miss...

Skyline views of Bath: Right on the southern edge of the Cotswolds, here’s my tip for stunning views over the World Heritage City of Bath: You might not have time for the whole six-mile Bath Skyline walk, but at least enjoy the bird’s eye perspective of Georgian Bath laid out below and the Mendip Hills beyond. It’ll make your heart sing.

[caption id="attachment_13698687" align="alignleft" width="153"]

Hugh Llewelyn via Wikimedia

Church crawling: I love church crawling–all life (and death) is here! St Mary’s Church, Painswick, is a favourite for its famously picturesque yews in the churchyard (a devilish legend says only 99 will ever grow) and ornate 17th/18th-century tombs of clothiers and wool merchants. Dating from the 14th century, with quaint lychgate, 173ft spire, Civil War cannon ball damage to the tower and the creamy limestone maze of historic streets around, it’s a quintessential English church.

Eccentric secrets: I’ve a predilection for the eccentric, so while world-famous Cotswold houses and gardens like Blenheim Palace are a must, do also drop into Snowshill Manor and Garden near the honeypot village of Broadway. “Never let anything perish” was the motto of collector extraordinaire Charles Paget Wade (1883–1956) and thousands of his eclectic treasures are here, from Samurai armour to musical instruments–plus a charming Arts & Crafts-style garden.

A forgotten treasure: Chastleton House near Moreton-in-Marsh was built between 1607 and 1612 by a prosperous wool merchant to show off his wealth and power. So far, so typical of the Cotswolds. Except that the family’s subsequently dwindling fortunes meant the house stood still for nearly 400 years. Now owned by the National Trust, Chastleton’s magical air of benign neglect is lovingly retained–even the cobwebs are cherished.

Siân’s previously published books include The Royal Homes in Gloucestershire. Her latest book, The Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, is due to be published in late spring. Celebrating the landscapes, architecture, customs and culture of the Cotswolds, it’s magnificently illustrated by photographer Nick Turner. More details at www.darien-jones.co.uk/

Comments