The paradox of Dartmoor is that it looks so empty, and is in fact so jammed with great stuff

[caption id="DartmoorVisitingtheDepthsofTime_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

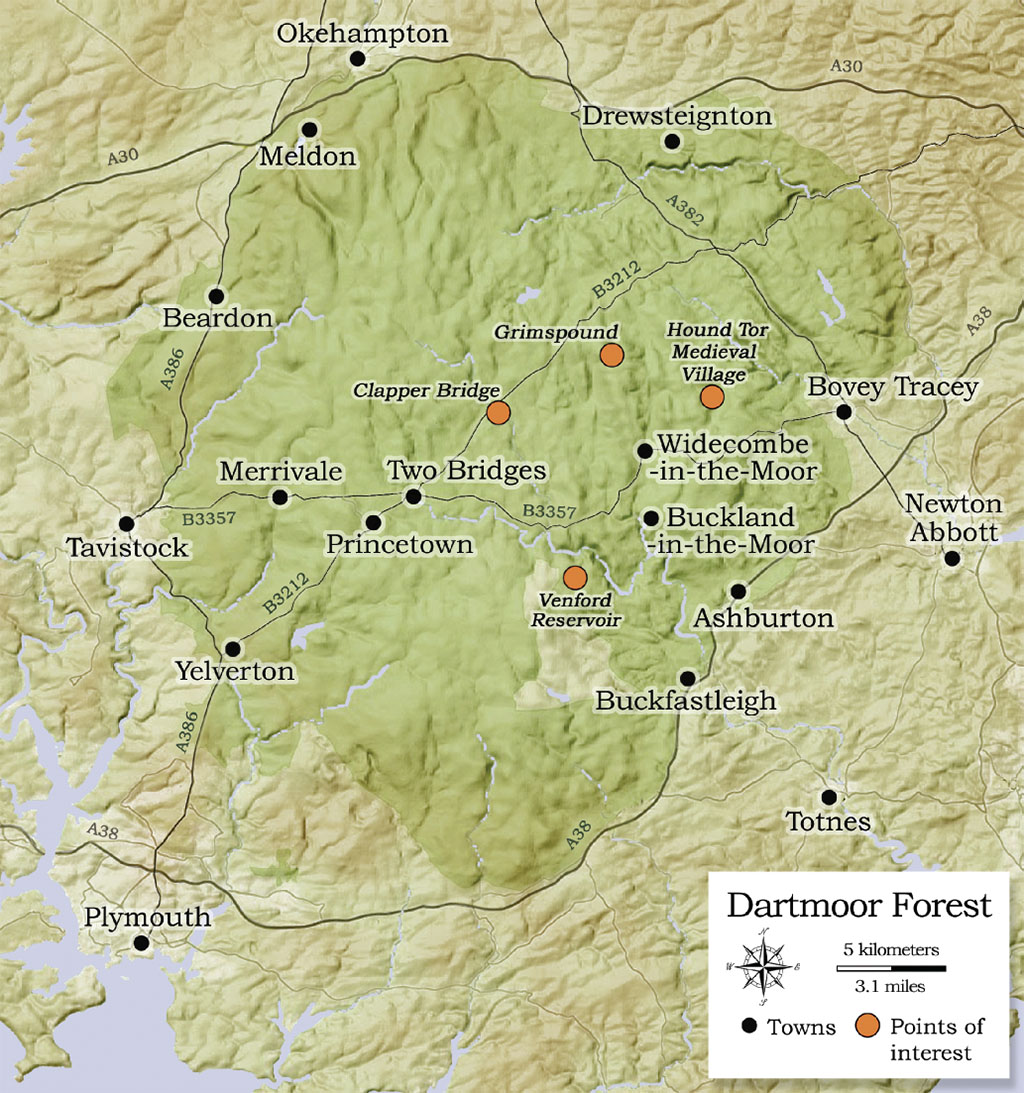

When my wife saw Dartmoor for the first time, she exclaimed in awe, “It looks like the American West.” Indeed, Dartmoor is remarkably like an oversized mesa, an oval 20 miles by 30 miles whose steep sides rise nearly 1,000 feet above the quaint vales that surround it. It’s a long, rugged drive up those sides, along narrow lanes tightly confined by stone walls and hedgerows, and when you suddenly crest out onto its top, the views are startling. “Look at the way grassy prairies roll as far as you can see, completely empty,” my wife continued. “And look at the way the rock spires stick up, like the hoodoos back in the Rocky Mountains.” A Dartmoor innkeeper had once made the same comment to me. “I like to go pony trekking through the center of Dartmoor and pretend I’m in the Old West,” he said.

Alike, yet not alike; as soon as you start looking for differences, you find them. Unlike the dry grassy basins of the Rockies, Dartmoor is soaking wet. Its verdant grasslands are painted in every shade of green that can be generated by environments ranging from damp to swampy to sink-and-disappear. Unlike the bowl-lands of the Western basins, Dartmoor’s swales and hills roll in odd and unpredictable directions, weirdly random, like a poem that won’t quite make sense. And those spires—while Western hoodoos and mesas are sharp-edged layer-cakes of warm colors, Dartmoor’s tors are gray and grainy, strange lumps of granite with odd, bulbous shapes.

Dartmoor’s granite tors are only the proverbial tip of the iceberg. The sparsely populated heath that dominates western Devon is a tableland with a granite top that protects the rocks underneath from eroding away. Water sits on the granite bedrock, pooling and puddling into swamps called mires, low points marked only by a sudden proliferation of sphagnum moss and the white, fluffy tops of marsh-loving cotton grass. The oddly disorienting curves of Dartmoor’s surface, as well as the tors crowning its hills, reflect the amount that the granite bedrock has dissolved. When the granite ends, rich patchwork fields suddenly spring to life, postage stamps lined by stone walls topped with hedges, their hominess contrasting wonderfully with the wilderness above them.

Of course, the granite lands of Dartmoor are no more “wilderness” than any other part of England, and their emptiness is only apparent. Dartmoor has been the scene of human activity for 6,000 years; 150 generations of humanity have filled it with things to see and places to explore. Post-Ice Age climate fluctuation has been the main controlling factor. In most centuries Dartmoor’s climate was too damp and cold for farming. During these cold centuries Dartmoor would be used as it is now, as managed common grazing, which keeps the land in grass and prevents the growth of trees. Then the warming would begin again, growing seasons would stretch and pioneers would once more enter the granitic uplands, creating the farms, fields and monuments typical of whatever culture was current. After a few centuries, the cold and wet would return, the settlements would be abandoned and the mosses would smooth their remains to forgotten lumps—cycles of humanity in deep time, preserved for our viewing.

[caption id="DartmoorVisitingtheDepthsofTime_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARJAN

The last Ice Age rendered human life in Britain extinct for 10,000 years. As the ice receded, around perhaps 10,000 BC, low sea levels exposed a land bridge where the English Channel is now, and the ancestors of the British simply walked across, following game herds into the newly formed grasslands. When these Late Mesolithic hunter-gatherers reached Dartmoor, they found it covered with an open, glade-lake forest, a fine hunting ground. Then, as agriculture became common in the Neolithic Period (c. 3000 BC), farmers removed all of Dartmoor forest, creating the unobstructed views we see today. These folk were but the country cousins of the great Neolithic builders of Stonehenge and Avebury 100 miles to the east. They erected no great monuments—except, of course, for the landscape itself, that “Western” style openness, a cultural feature maintained generation after generation for 5,000 years.

[caption id="DartmoorVisitingtheDepthsofTime_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

GREGORY PROCH

Monuments came to Dartmoor as metallurgy entered northern Europe. The Bronze Age gets its name from its most common and useful alloy, common copper hardened with rare tin so it could keep an edge. Dartmoor had tin, and lots of it, formed in veins at the places where granite extruded through the older rocks. When the rock around a tin vein weathered, tin dust would wash down the streams to form placer deposits, much like the gold deposits of the West. This Dartmoor tin was commercially mined on a large scale and shipped overseas, starting no later than 1750 BC (when a Phoenician ship full of ingots sank in the River Dart), and continuing past AD 1800. Flush with wealth, Dartmoor’s Bronze Age tin-mining residents built a series of megalithic monuments, roughly contemporaneous with Stonehenge’s last phase, when bluestones allegedly imported from Wales were erected.

The Grey Wethers is a set of two large stone circles hard by each other, beautifully complete after an 1898 restoration, sitting on a wide, empty expanse of grassland a three mile hike north of Post-bridge; the approach path is a spectacular (if difficult) wander through open moor, along the River Dart, and past other, lesser Bronze Age remains. Easier to reach, and stunningly evocative, are the two stone rows at Merrivale just off the B3357, each a double line of standing stones almost 900 feet long, plus a 12-foot standing stone and a stone circle in ruinous shape.

‘DARTMOOR’S SWALES AND HILLS ROLL IN UNPREDICTABLE DIRECTIONS, LIKE A POEM THATWON’T QUITE MAKE SENSE’

[caption id="DartmoorVisitingtheDepthsofTime_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARJAN

Visiting Dartmoor

You’ll find Dartmoor National Park’s official website at www.dartmoor-npa.gov.uk. Of more interest to visitors is their separate tourism site, www.virtuallydartmoor.org.uk. An excellent independent site, Exclusively Dartmoor (www.exclusivelydartmoor.co.uk) gives you access to Dartmoor accommodations, inns and other businesses. A second independent website, www.legendarydartmoor.co.uk, has an incredible collection of pages on Dartmoor’s history and legend. While the Venton cottages and b&b have no separate web sites, they can be easily found in Exclusively Dartmoor. The enormous pit of the Shaugh Lake China Clay Works abuts the national park, and can be viewed from the park’s Blackaton Cross trail-head on the mine’s northern edge.

[caption id="DartmoorVisitingtheDepthsofTime_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARJAN

A second period of Bronze Age settlement, around a short warm spell (c. 1300 BC), left behind entire settlements, including extensive sets of field walls called reeves. Built of stone in the deforested plateau and abandoned around 1100 BC, they preserve an entire culture. Mostly they are low mounds of moss and grass, impossibly straight and going on for miles; other mounds, running off at right angles, are the stone walls of fields, and have circular mounds in their corners, the remains of houses and barns.

Villages of circular houses also exist, Grimspound (near Post-bridge) being the most famous and impressive after its 1894 restoration—a set of 24 hut circles within the low remains of an impressive wall. You can see another hut settlement as you approach the Merrivale Stone Rows, and a set of farms appears uphill on your right as you hike towards the Grey Wethers. One of the largest sets of field boundaries appears along the Venford Reservoir Road, and can be viewed by looking westward across the valley from the Dartmeet B3387.

Until the modern age, the medieval period was Dartmoor’s busiest time. Not only did the era’s booming international trade bring wealth to Dartmoor tin miners, up to about 1300, its climate was as warm as our own today. Agriculture once again crept high atop the plateau, only to retreat after 1400 under an onslaught of cold weather. The best preserved of the lost medieval settlements sits below Hound Tor, itself one of the largest, most easily reached and most interesting of the moor’s tors. The village, excavated in the 1960s, now consists of exposed foundations that clearly delineate its form, with impressive views beyond.

Villages farther down from the moor top did better than Hound-tor (as it was known), as wool and tin exports expanded. Medieval wealth built a series of churches, none more stunning than St. Pancras at Widecombe-in-the-Moor, a tiny village set in a pocket of quiet beauty in the midst of the moorlands; known as “the Cathedral of the Moors,” St. Pancras’ 120-foot tower can be seen for miles around.

The most ubiquitous of the medieval monuments, however, are the great stone bridges, built by the tinners so that the floods, increasingly frequent after the end of the warming, wouldn’t stop their trade. These are long and graceful multi-arched structures, built wide enough for wagons and used by automobile traffic today. You’ll cross two of them on the road between Ashburton and Two Bridges, with three more in the Drewsteignton area.

Other stream crossings of the era used clapper bridges made of giant slabs of granite; when a flood washed one of these away, the tinners would simply haul the stones back and re-erect them. As the clapper bridges are impossible to date, some people speculate that they could date to the earliest days of tin mining, deep in the Bronze Age. Several clapper bridges survive, mostly as ruins, but the Postbridge clapper is kept in repair and is open to foot traffic. Between the bridges, stone crosses led travelers through the midst of the moors, guiding them around the dangerous mires, and many of these crosses survive as well.

‘IN THE NORTHERN THIRD OF DARTMOORYOU FIND THE HIGHEST TORS AND THE DEEPEST, WILDEST GORGES’

[caption id="DartmoorVisitingtheDepthsofTime_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARJAN

The postmedieval period brought one of Dartmoor’s most characteristic features: the thatched farmhouse below the moor’s edge. Thatch remains particularly common along the farmlands of the eastern edge, and your chance of coming across a quaint old cottage is good as soon as you drop off the plateau into the rich lands below. Such survivals are mainly a matter of luck. These are the buildings that still had thatched roofs when the region came under historic preservation laws in the early 1950s; their large numbers show that the Dartmoor freeholders had been too poor to modernize their roofs before government planners entered the picture. Of course, thatch today is a highly desirable symbol of both cultural identity and wealth, but back then, it was an expensive, short-lived, mouse-infested nuisance.

One of the finest concentrations of thatch can be found along the narrow lanes that radiate from Widecombe-in-the-Moor. Here the tiny Webburne River has carved a notch of lush farmland deep into the moor, and small, rich fields, lined with stone-based hedgerows, fill its narrow valley and climb its sides to the edge of the granite. The valley’s many thatched farmhouses, mostly dating from the 17th or 18th century, add to its charm, among them Upper Venton Farm, a half mile south of Widecombe and easily visited. Its large stone farmhouse is clad in rich, thick thatch, and bears a date stone from 1733. The one-time home of early 20th-century romantic novelist Beatrice Chase, it is now a bed and breakfast inn. Its fine old stone barn and stable is now converted into two luxury cottages. The high fields around the farmstead give a stunning view over the valley, with the tall tower of Widecombe’s church standing like a lighthouse.

Modern times have, of course, added their layers to Dartmoor. Most visually impressive are the open pit kaolin (or “China clay”) mines at Dartmoor’s southwest corner. These massive holes, bone white and still in operation, scrape up to the very edge of the moor, an amazing (if dismal) sight. Although unsightly, the mines are at least limited; not so the large tracks of green-black conifers, planted in regimented rows. Established during World War I to counter the Kaiser’s blockade of Norwegian lumber, these government-owned tracts have long since become an end in themselves, surviving any number of Tory and Labour administrations. They are missing only on the northern third of Dartmoor, a region given odd protection as a military training base, its edge marked with lines of tall posts that stretch to the horizons. This vast area is pathless, yet open to the public on most days and all weekends. It is here that you can best experience the old emptiness of the moors. Here you find the highest tors (topping 2,000 feet, the highest points in England south of the Pennines), and the deepest, wildest gorges.

Still, the 20th century’s greatest contribution to Dartmoor was the decision to leave it be. In 1951 Dartmoor became one of Britain’s first national parks—not a government owned reserve as in America, but rather a planning designation more akin to zoning, and aimed at protecting its scenic beauty. It is due to this that Dartmoor greets its visitors with patchwork fields, thatched cottages, quaint villages and open vistas. The final act of the modern era so far has been to prevent the erasure of previous eras, to preserve deep time in Dartmoor.

Comments