Keeping island invaders at bay for 2,000 years

Henry VIII stood at Southsea, presumably with legs akimbo, as the naval Battle of The Solent played out in mid-July 1545. The French threat was real and present, and the Mary Rose, one of King Henry’s prize ships, sallied out to see off the invaders. Poor Henry watched helplessly as his precious ship sank, taking all but three dozen of more than 400 souls to the bottom.

The Solent separates the English mainland from the Isle of Wight. It is around 20 miles long and 2½ to 5 miles wide, although just over a mile at Hurst. This strait has been a potential in-road to invaders for centuries, attracting the attention of kings and governments keen on defending The Solent.

Stone leviathans on both sides of the water mark attempts to defend this coast. It is a story of Henry VIII, a monarch with a proclivity for the scaffold, and another king, Charles I, destined for the same place. It is a tale of French, Spanish and, latterly, Germans, all keen to breach this “moat defensive.” Four Henrician castles feature, plus two others with even longer histories.

[caption id="DefenseoftheSolent_img1" align="aligncenter" width="657"]

MARY ROSE FOUNDATION

A Lymington ferry took me to Yarmouth, on the western end of the Isle of Wight. Its castle at the harbor seems hemmed in today by encroaching building with one entrance in the garden of next door’s George Hotel. This was my first brush with the chain of forts Henry devised to defend the south coast against French attack, a threat more prescient after France’s alliance with the Holy Roman Empire in 1538. Suddenly, Henry’s break with Rome portended Catholic cohorts tramping ashore, with Henry’s unseating their objective. Yarmouth differs from earlier castles in being designed with artillery in mind. Warfare was changing. The castle is squat, with England’s first arrowhead bastion in one corner, enabling flanking fire along the walls. Earth banking was designed to support heavy guns.

Henry’s castle building was costly. From 1538 until his death in 1547 Henry spent £120 million in today’s money funding castle building here, and beefing up defense in England’s remaining French territories.

In the island’s interior, Carisbrooke was a Norman creation, started by one of the Conqueror’s henchmen. Defenses were strong, for when the French came calling in 1377, Carisbrooke held, its constable (aptly, Sir Hugh Constable) forcing withdrawal on their commander’s death. The French burned Yarmouth town; Carisbrooke Castle represented sterner stuff.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="488"]

At the castle today, memories abound of its most famous resident, King Charles I, who was brought here ostensibly by his friends in November 1647, still hopeful some settlement might be agreed with Parliament. Charles was attempting to use Scottish troops to continue the conflict, however, and the guest soon became a prisoner. He launched three escape attempts, the window featuring in one still a draw today. During his captivity he played bowls on a green laid out for him within the curtain walls. After a year here, the Charles cavalcade moved to Hurst. Its chapel is the island’s war memorial; Charles is commemorated here, too.

If Carisbrooke (like any castle) was to withstand siege, it needed water. Visitors enjoy the well-house, where mulepower raises the vital commodity. After watching all that physical effort, any thirst can be quenched at the handy tea room.

The castle was less fortunate during the English Civil War, when its Royalist governor was hoodwinked by a surprise night attack, capitulating without a shot. The following century saw further strife when a fire’s hot embers fell into the powder room; the resulting explosion killed 17. Southsea illustrates how The Solent’s defense spanned eras and conflicts. It was strengthened against Bonaparte, and then improved again at the time of Napoleon III, gaining two outer ramparts. Southsea is also a good vantage point from which to see four sea-forts built in The Solent between 1864 and 1880. The nearest of these, Spit Bank, can be seen clearly from Southsea’s ramparts. Within the last century, the castle was again garrisoned in both world wars.

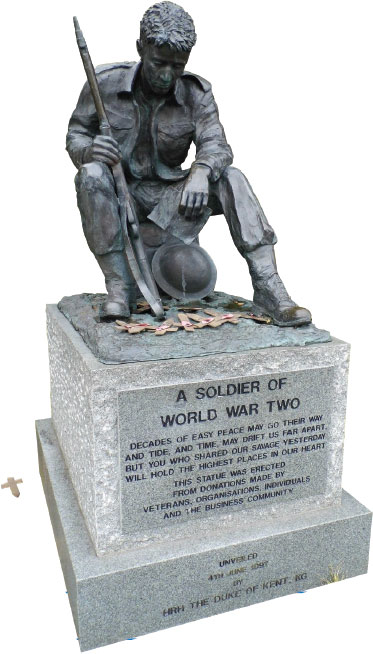

The role of Southsea (and Portsmouth) in national defense is illustrated by the nearby D-Day Museum and war-memorial, plus the ships collection at Portsmouth’s historic dockyard. Among its treasures, the dockyard houses the raised Mary Rose, the only 16th-century warship on display in the world.

Just west of Portsmouth lies Portchester Castle, a further reminder that defense began long before Henry. Portchester is England’s best surviving Roman fort. The walls are remarkably well-preserved and provide a nine-acre walled garden for families enjoying picnics in rare English sunshine.

After the Romans left, Portchester remained uninhabited until men of God arrived in the early 12th century and established an Augustinian priory in the southeast corner. Peace would not reign here, though, for Henry I began the stone keep in the opposite corner around the same time.

Portchester also illustrates another purpose of these citadels. The fortress became a prison during the 17th-century Dutch Wars and later the Napoleonic Wars, with more than 4,000 men held here. A possibly apocryphal story tells of a senior officer visiting the governor, leaving his horse at the gate, and returning a few hours later to find hungry Frenchmen had pinched it. The keep includes models showing the castle’s development from Roman fort to prison.

The approach, up Castle Street, is an idyllic jumble of thatch and an occasional blue plaque. Unusually, there is a tea room within the walls of St. Mary’s Church.

If it is possible for a castle to be intimate, it is little Calshot on the end of its sand spit. The Henrician blockhouse was constructed to defend Southampton’s harbor entrance. The central tower, 16 yards in diameter and 10½ high, unusually possesses an octagonal ground floor and basement, but two circular upper stories, another geometrist’s pleasure.

Henry VIII’s break with Rome caused him problems, but his subsequent Dissolution of the Monasteries enabled him to capitalize on it, and here it is believed stone and structure came from ruined Beaulieu Abbey. There’s an intimacy illustrated by the barrack room, which looks more homey than many youth hostels I’ve frequented.

Calshot Spit is more than a Tudor castle. There was a military base here until 1953, with boats heading to Dunkirk and Normandy. T.E. Lawrence was based here incognito after his Arabian adventures, and Schneider Trophy seaplane races were held here.

Situated at the end of a two-mile shingle beach facing the Isle of Wight, Hurst Castle appears close enough to touch. If the walk is too much, there is a ferry from Keyhaven.

Hurst commanded The Solent’s western entrance from its completion during Henry’s declining years right through to World War II, when it hosted an anti-aircraft battery. While similar to Southsea and Calshot, Hurst was bigger, beginning as a 12-sided tower with curtain wall and three large semi-circular bastions.

[caption id="DefenseoftheSolent_img6" align="aligncenter" width="885"]

DANA HUNTLEY

DANA HUNTLEY

Time was running out for King Charles I when he arrived from Carisbrooke. He was on his way to London and an axeman. He’d arrived on November 29, 1648 by boat and left around three weeks later. The king had a second floor room, effectively a cell, just 8 feet by 4½; there was no more lip-service to the suggestion that he was a guest.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="884"]

STEPHEN ROBERTS

In the early 1860s, the castle was enlarged and built around, so that today it is only from the inside you can appreciate the shape and size of the original. A narrow-gauge railway transported shells to the fort’s naval guns, surely the only English castle to have a railway across its drawbridge! There was an ingenious lift from the basement magazine, conveying shells to the ground floor. The entrance in the northwest bastion was protected by an unusual caponiere, which enabled the moat to be flanked with musket fire, should anyone attempt a land attack. Henry would barely have recognized a place that had become all mod-cons. Castles may have been static, but their defense evolved.

Richard II built a great hall at Portchester as the 14th century waned. As I pottered away from Hurst on the Victoria Rose, it was apt my thoughts turned to Shakespeare’s play of that name: “A moat defensive … this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.” The Solent and its castles did their job.

WHERE TO STAY

10

10

STEPHEN ROBERTS

STEPHEN ROBERTS

The Windsor Carlton guesthouse overlooks the sea in Ventnor, handy for Carisbrooke and Yarmouth. Edward Elgar honeymooned next-door. The George Hotel is next to Yarmouth Castle and is a former townhouse belonging to the island’s governor.

The Red Lion in Fareham is just over three miles from Portchester, and handy for other mainland castles. It is a 1763 coaching inn.

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="373"]

STEPHEN ROBERTS

EATERIES

Carisbrooke’s tea room serves light meals and snacks. Southsea has a courtyard tea room. Refreshments are also available at the D-Day museum.

Take lunch, too, at Southsea Tennis Club’s Pavilion café.

Portchester has a tea room inside St. Mary’s, and the Cormorant pub serving meals up the road.

There is a café in the Sunderland Hangar at Calshot. Hurst’s tea room serves light snacks, while the Gun Inn, an 18th-century pub, serves food in a walled garden at Keyhaven, handy for Hurst’s ferry.

PLAN A VISIT

English Heritage

Southsea Castle

Hampshire History

Historic Dockyard

Comments