Along the River Tweed with Sir Walter Scott

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img1" align="aligncenter" width="403"]

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

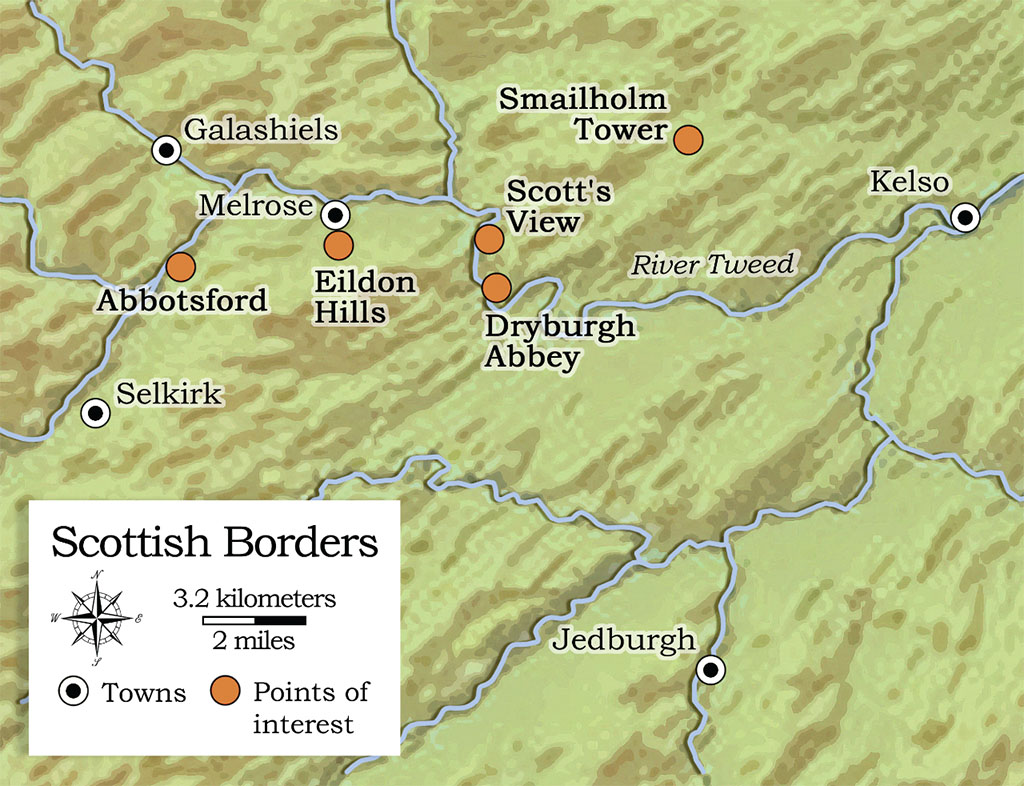

It is said that, after Sir Walter Scott’s death in 1832, his horse would always stop without bidding at a certain place in the highway where a broad view opened up across the valley of the River Tweed: Scott’s View, as it is now marked on the government maps. Scott himself had visited this place so often, and stopped so invariably, that his horse would halt automatically. It is indeed a grand view, the whole of the rich Tweed Valley opening up before you, the triple stacks of the Eildon Hills (remnant volcanic cones) standing in its center and the river itself twisting directly beneath your feet, forming a great loop that bumps against the foot of a cliff. Scott’s last stop here was his funeral procession.

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img2" align="aligncenter" width="152"]

JIM HARGAN

It was not just the beauty that entranced Scott. This view laid out, in one sweeping panorama, the physical and spiritual heart of the region that Scott loved above all, his home and favorite subject, the Borders of Scotland. To the right lay the earthworks of the Roman fort Trimontium, where the Borders first entered written history. Directly underneath, within the gorge-like meander of the River Tweed, sat Old Melrose, the site of the 7th-century monastery of the renowned Saint Cuthbert, born a shepherd lad in the hills nearby. At the center, the rough Eildon Hills mark the place where Thomas the Rhymer lost himself in Elfland for seven years, becoming slave and lover to the Queen of Faerie. And all around lay a rich patchwork of prosperous fields, bordered by hedges and forests, framed by the empty wilderness of the surrounding hills.

For Scott, the apparent prosperity of that patchwork landscape was deceiving. Scott’s “Borders”—a single, distinct region, centered on the River Tweed—was an edge land, a rough land, a backward land, whose peasant inhabitants remembered the tales of the Reivers, brave Scottish patriots raiding across the border into England, and preserved these tales as ballads. Scott, a lawyer, became rich from writing romantic poems and novels about these Borderers and other Scots, and with this money built Abbotsford, his baronial estate on the River Tweed just south of Melrose. It’s a fascinating and beautiful place in its own right, and doubly worth visiting for its association with Scott—for never has a house more clearly reflected its owner. You’ll find it a gray-stoned hall in the Romantic style, more restrained and graceful than later Victorian piles, built (to Scott’s design) in the form of a pele tower with turrets and castellations. Fine gardens, beautifully kept, surround it, including a sunken walled garden in which a carved stone Morris perpetually pleads forgiveness from the wife of Rob Roy.

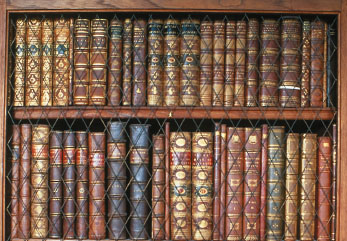

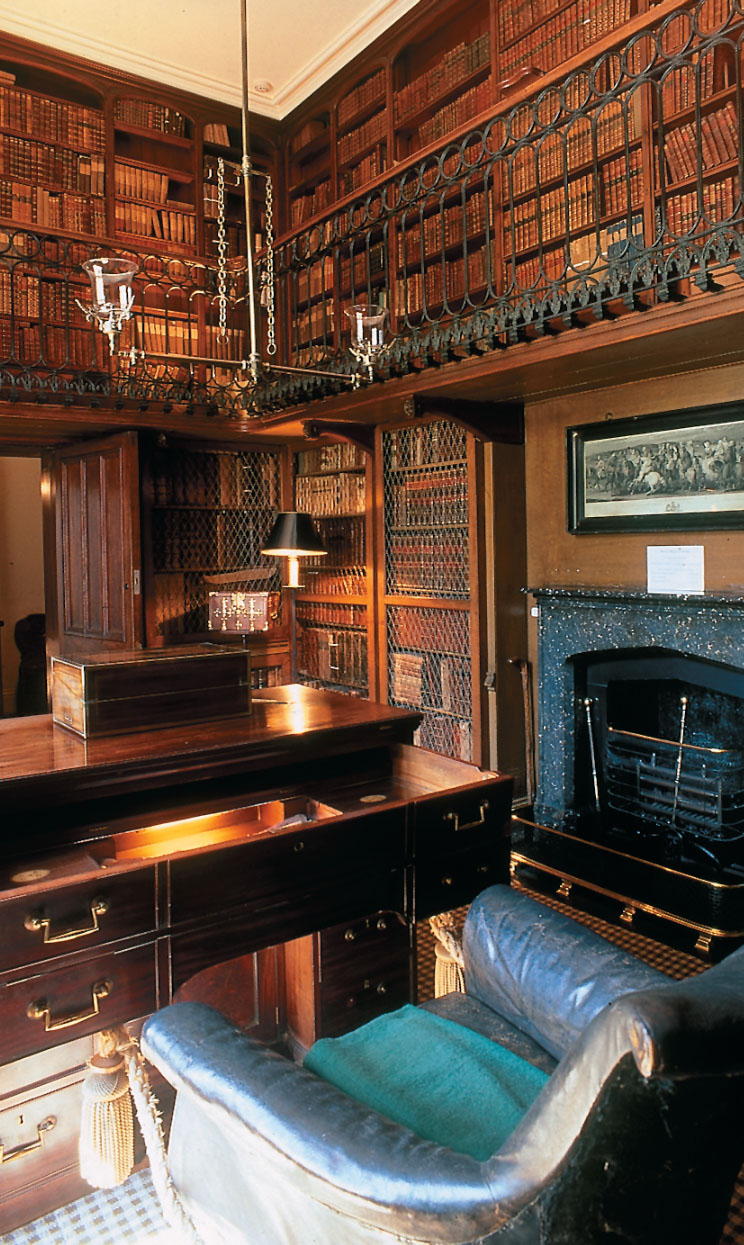

It is, however, inside Abbotsford that Scott reveals himself, for Scott’s descendants, who lived in Abbotsford until 2004, kept the core of the house almost exactly as Scott left it upon his death. Here you’ll find medieval armor superbly mounted, a wild collection of knives, swords, pistols and muskets of all sorts, and such curiosities as a chair carved from the last surviving beam of Rob Roy’s house and an exact reproduction of Robert de Bruce’s skull. Scott’s collecting reached its apogee in his 9,000 book library, beautifully set out in its own room, the books still arranged as Scott left them. The books overflow into the most telling room of all, his study, a 16-foot cube, the top half occupied by a book-lined gallery set off by an iron catwalk.

Despite all Scott’s historic Romanticism, his goal was forward-looking; he wanted a pan-Scottish nationalism based on historic pride, functioning to unify Scots in a new age of prosperity. To this end Scott had many irons in the fire, but none quainter than St. Ronan’s Border Games, organized by Scott and his shepherd friend James Hogg for mid-July at Innerleithen.

Innerleithen is a glorious little Borders town along the Tweed River in the midst of its most wild and remote section, 15 miles upstream from Melrose, with whitewashed stone buildings climbing up the gorge-like north side of the River Tweed. The games, first held in 1827, remain the high-point of village life. Festivities are led by St. Ronan himself, in the person of the best boy student at the local school. The celebration climaxes as St. Ronan “cleekits” the devil—reenacting the deciding moment in Innerleithen’s mythic history when St. Ronan hooked the Devil by the hind leg with his Cleikum Crook and tossed him down a local well (natural spring). Even if you miss the festivities, don’t miss a visit to that devilish spring, St. Ronan’s Well, once a spa and the subject of a Scott novel, now a handsome local garden and museum. There’s much else in the town as well, including grand views from a local fort-ringed hill, some fine antiquities, a handsome High Street and Robert Smail’s Printing Works, run by the National Trust for Scotland the way a Border village printer would operate in the 19th century.

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img3" align="aligncenter" width="347"]

JIM HARGAN

How Sir Walter Scott Did It

Sir Walter Scott chalked up an impressive list of achievements. He created modern Scottish nationalism out of whole (tartan-woven) cloth, lighting on Gaelic Highland culture as a means of unifying modern Scots, much as the macAlpin kings did during high medieval times. (Curiously, the more the macAlpin heirs became Anglo-Norman, the more they favored ostentatiously Gaelic court rituals.) Scott’s antiquarian interests led to his co-founding (coincident with the Brothers Grimm) the academic discipline of folk studies. He quite intentionally set the foundations for the modern wool industry in the Borders, using his influence to make fashionable the local weave, first known as “Shepherd’s check” and now known as tweed. Most importantly, his novels generated, through the Brontes, Dickens and Hardy, the forms and traditions of novel-writing still with us to this day.

Scott did one more remarkable thing: he got rich from writing. No one had ever done that before. From the first, lawyer Scott used his position and connections to involve himself, actively and financially, in all stages of publication. He had a local “publisher” who acted more as a modern agent, who then made arrangements for printing and distribution with a top Edinburgh firm, which then sold copies to wholesalers throughout the world. Scott accepted his cut in advance as a promissory note, which he would then sell immediately at a discount. This note would typically be from his Glasgow publisher, and would be backed by a second note issued by one of the wholesalers as a commitment to purchase the book.

In other words, Scott got rich by investing in collateralized derivatives ultimately backed by the sale of his own books – and if this sounds very 2009 to you, so will the sequel. In 1825, Scott’s London wholesaler used Scott’s future sales as collateral on a margin loan they then spent speculating on, of all things, hops futures. They lost it all. Their bankruptcy left Scott’s Edinburgh printers holding worthless paper that they had used to collateralize over a quarter of a million pounds of promissory notes; they too went bankrupt, paying 2s 9d on the pound (14¢ on the dollar) to angry creditors. Scott had received nearly half of these notes, but had sold them off. Under the law of his era, Scott still wasn’t off the hook—except that he had already sheltered all his Abbotsford assets (basically everything) in a trust in his son’s name, immune from his creditors. He had skated—yet he promised to make good the entire amount anyway, £116,848 11s 3d to be exact. And he did, by writing two novels a year until his early death, perhaps brought on by exhaustion, in 1832. His son, Major Sir Walter Scott, paid off the last three pence, as promised, in 1848.

J.H.

‘TODAY THE ABBEY IS A GRAND RUIN IN ROSE-COLORED STONE, FAMED FOR ITS ELABORATE CARVING AND FANCIFUL STATUARY’

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

GREGORY PROCH

For the picturesque Borders of Scott’s novels there’s no better site than the one that gave Scott his lifelong obsession with the romance of history—Smailholm Tower, eight miles east of Melrose. Nowhere will you find a more ruggedly windswept, stunningly Romantic site than this isolated single tower set among rocky outcrops at the top of a crag, a small loch by its foot. Scott lived from age 3 to 7 with his grandparents at the adjacent farm, recovering from polio.

Smailholm simply overwhelmed young Scott, and no wonder; it’s a strange sight, tall and thin against a grim landscape, with improbably slender lines unbroken by outbuilding or courtyard. Its odd appearance was a response to the insecure times between 1300 and 1700, a distinctive architecture known as a tower house or pele tower. Meant to repel robbers rather than armies, these castle-like houses had kitchens and utility storage on the windowless ground floor, servants on the next floor and the family on top, all linked by a very defensible internal spiral stairway. When robbers struck, the cattle would be herded into the ground floor. The robbers were known as reivers, and they were mainly after the cattle.

‘ABBOTSFORD IS DOUBLY WORTH VISITING BECAUSE OF ITS ASSOCIATION WITH SCOTT—FOR NEVER HAS A HOUSE MORE CLEARLY REFLECTED ITS OWNER’

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

The time of the reivers started in 1296, when England’s Edward I “Longshanks” launched his nearly successful attempt at conquering Scotland. The next 60 years saw the whole of Scotland enveloped by the Wars of Scottish Independence; but in the Borders, lawlessness, war and civil strife continued for three more centuries. Deep in the hills above the Tweed, on both sides of the border, clans with English names, English language and Celtic culture rode forward to claim broad areas defined by family, forcing tenants and yeomen to pay “blackmail” as the illegal tax for mob-style protection was called, and despising the King’s law. The clan chieftains reverted to the old Celtic way of counting wealth in cattle, raiding competing families for cattle and holding blood feuds that lasted for generations. Scott (whose ancestors were among the most notorious of the reivers) painted the reivers as patriots who attacked the English and maintained a rough code of chivalry, but this was simply untrue. The reivers knew only clan loyalty, attacking and murdering (sometimes with horrific brutality) Scots and English alike.

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img7" align="aligncenter" width="477"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img8" align="aligncenter" width="744"]

JIM HARGAN

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img9" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

It was not always so. For centuries before, the Tweed Valley had been united in the same kingdom (English during the Dark Ages, Scottish during medieval times), a prosperous land whose river served as a highway to the sea. Starting around 1115, the kings of Scotland planted abbeys as tools of polity, and these abbeys organized a great wool trade that made them and the Tweed Valley rich. The greatest of these was, and remains, Melrose. Oddly enough, it received its present grandiose form only after things fell apart, as its original 12th-century architecture would have been undecorated as befitting a house of ascetic monks. It was, however, destroyed by the English in 1322 and 1357, and each time restored by royal builders out to make a point about their power. Today the abbey is a grand ruin in rose-colored stone, famed for its elaborate carving and fanciful statuary. Located next to the High Street of the pretty town of Melrose, it’s a lovely place, surrounded by parks and a short walk from the River Tweed.

Three other abbeys survive close by as intriguing ruins. Dryburgh’s ruins are the most extensive, sitting isolated in meadows along a bend in the Tweed about four miles downstream from Melrose. In contrast Jedburgh, eight miles south of Dryburgh, has been swallowed by the market town that it fostered. Kelso Abbey, 10 miles down the River Tweed from Dryburgh, has faired the worst and survives as a single tower surrounded by a busy High Street, with a stunning view from its medieval bridge.

THE BORDERS: HITHER AND YON

Abbotsford is located between Melrose and Galashiels, a short distance south of the A6091 (the main east-west highway) on the B6360. Open daily, mid-March through the end of October. Adults £7, children £3.50; gardens only, £3.

www.scottsabbotsford.co.uk

St. Ronan’s Well Interpretive Center is on the northwest edge of the village of Innerleithen; take the A72 to the west end of the village and look for the brown sign. It is open normal business hours in season, and is free.

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img10" align="aligncenter" width="413"]

COURTESY OF SCOTTISH BORDERS COUNCIL

Smailholm Tower is six miles east of Melrose; take the B6404 east from St. Boswells and look for the brown signs. It’s open daily, 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., April through October. Adults £3.70, children £1.85. For its Web site, go to www.historic-scotland.gov.uk, and put “Smailholm” in the search box.

Melrose Abbey is in the village of Melrose, just to the north of the town center. It’s open daily all year, 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Adults £5.20, children £2.60. www.historic-scotland.gov.uk, and “Melrose” in the search box.

Traquair House, the oldest inhabited castle in Scotland, is south of the village of Innerleithen via the B709 for 1.4 miles, then right on the B7062 for 0.4 miles. Its typical hours are noon to 5 p.m., daily from April through October; check the Web site for details. Adults, £7, children £4; gardens only, £3.50 per family. Also on the property are local craft artists and a tea house; bed and breakfast is also available. www.traquair.co.uk

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img11" align="aligncenter" width="131"]

JIM HARGAN

Floors Castle is just outside Kelso, off the A6089. It’s open mid-April through October, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Adults £7.50, children £3.50; gardens only, £3.50 per adult, children free. www.roxburghe.net

Lochcarron of Scotland is located in Selkirk, on Dunsdale Road. It’s open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Saturday, and admission is free. www.lochcarron.com

However, to best appreciate the sweep of Borders history, visit Traquair House, a mile outside Innerleithen. This spectacular tower house has been continuously inhabited since at least 1107, and by the same family, the Earls of Traquair, since 1491. It’s a stark rectangle, almost undecorated but for its brilliant white plastering, four stories high and with a jog in the center allowing a clear arrow shot over the front door. It started as an unfortified royal hunting lodge during the safe times of the late 11th century; this was expanded, and then converted to its current semifortified shape as the reivers, rather than the king, came to control the countryside.

‘NOWHERE WILL YOU FIND A MORE RUGGEDLY WINDSWEPT, STUNNINGLY ROMANTIC SITE THAN THIS ISOLATED SINGLE TOWER AT THE TOP OF A CRAG’

[caption id="DiscovertheScottishBorders_img12" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

JIM HARGAN

When peace came to the Borders in the early 18th century, the family added low wings flanking the front to form a courtyard, and this elegant little touch was the last substantial change ever made. The rooms on show let you see how the nobility lived in the unsafe times, and include a priest’s room and bolt-hole, as the Traquairs were devout Catholics. Also on-site is an active brew house, founded by the 20th earl in the 1960s, one of Britain’s earliest modern microbreweries; you can sample its excellent product in a special room by the gift shop, or enjoy it by the pint at the Traquair Arms, in the village.

The last wave of violence in the Borders came as religious conflict and persecution, as Scotland became sucked into the English Civil Wars of the mid-17th century and added to them her own conflicts over Presbyterianism, which the Stuart kings opposed ruthlessly. The Stuart monarchy effectively ended in 1688 and the Border violence with it. Border lairds who had backed the wrong horse, such as the Traquairs, slowly sank into obscurity; but lairds who backed the Presbyterian cause had front seats and deciding votes in the 1707 parliament that unified Scotland with England in a breathtaking blizzard of bribery.

Within a decade Presbyterian lairds became Great Lords on the English scale—and largely remain so to this day, their ancient holdings still intact. Of these, Floors Castle is particularly stunning, sitting on a bend in the River Tweed just outside Kelso. Unlike Traquair, Floors has not a drop of castle in its blood; it is, instead, a massive residential showpiece, built by the Scottish architect William Adam in the 1720s, then expanded and romanticized by the Victorian architect William Playfair. Still the home of its original family, the Dukes of Roxburghe, it represents the birth of the modern Borders just as Traquair is the end of the old Borders.

The modern Borders, like the medieval Borders of the abbeys, got its character from wool. This time, however, there was a difference; the wool was woven, as well as raised, in the Borders. Once again, Sir Walter Scott had a leading role. Scott promoted “Shepherd’s checks” as a fashion, and by the 1840s this method of weaving had taken on a wide variety of patterns and its current name, tweeds. The mills also took up another fashion promoted by Scott—tartans. Tweeds and tartans are still manufactured today as highend export items, and one of the plants is open to the public. Lochcarron of Scotland produces tartans from their mill on the Ettrick Water in Selkirk, and offers tours as well as a visitors center and gift shop. Also worth a visit is the old court of Selkirkshire, restored to look is it did when Scott was its sheriff (or magistrate).

Most of the mills, however, are gone, and the railroads that served them torn up, their graceful viaducts still flying, empty, over the River Tweed. The contemporary Borders you visit is a tranquil backwater, where quiet roads connect old-fashioned towns, much like other places in Britain were 30 years ago. A checkerboard of fields, created by the Great Lords in the 18th century, has somehow never been grubbed up; the wild lands above have yet to be plowed. Lanes explore both, giving broad views framed by forests and farms. For the time being at least, the Borders remains the land of reivers and abbeys, the land beloved by Scott.

Comments