Between a Peaceful England and The Wild North

[caption id="DurhamofthePrinceBishops_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

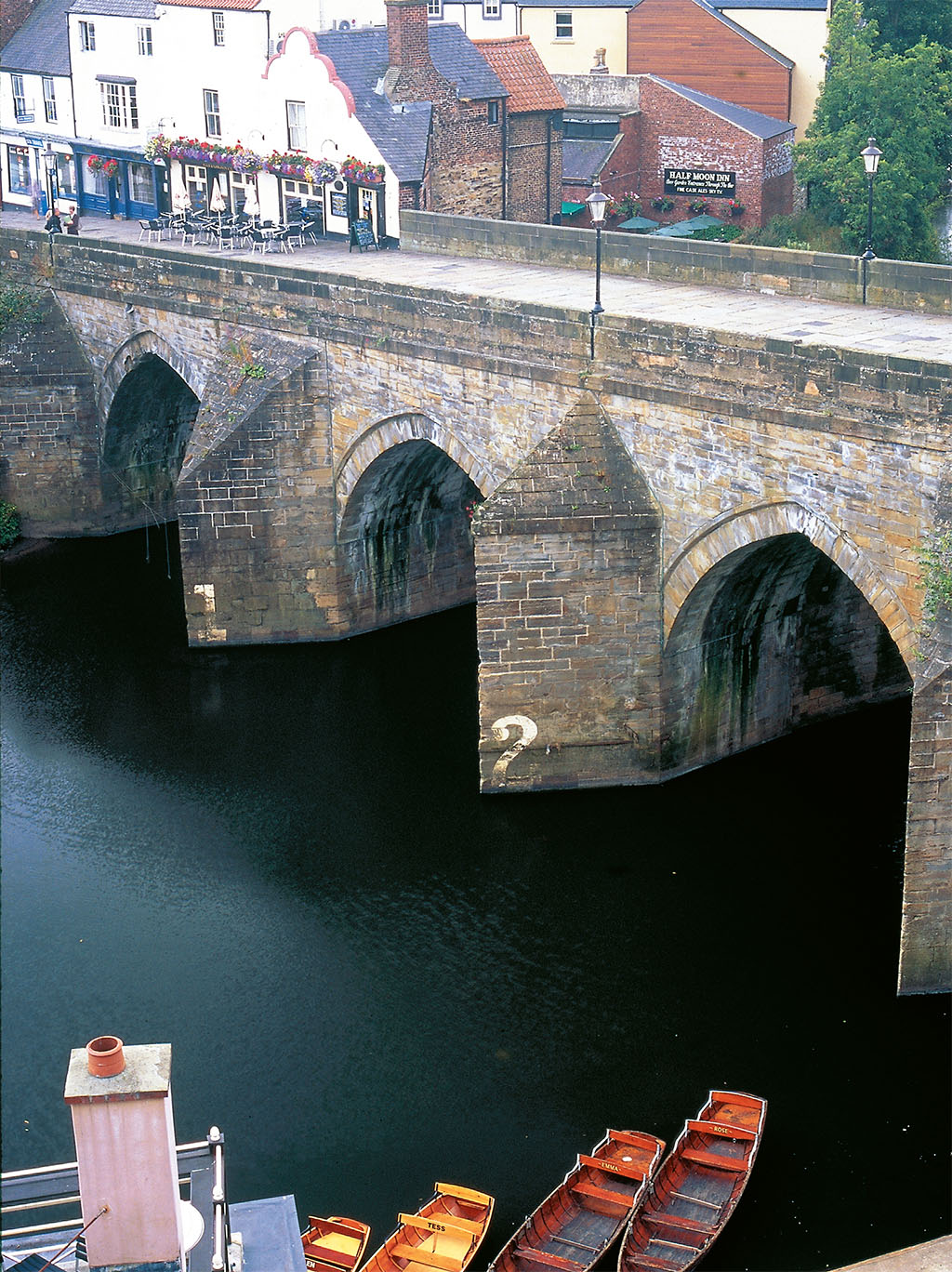

ONE OF BRITAIN’S MOST PICTURESQUE county towns sits amidst cliffs and rivers in the Northeast of England, not far from Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Durham crowns a cliff-edged meander on the River Wear, a loop that’s a bit over a half-mile long and not quite 800 feet wide at its narrowest section. At the high point of this peninsula, almost 100 feet above the river, perches one of England’s largest and oldest cathedrals, as well as a major castle that’s been converted into an important university. Inside the landward neck of the peninsula is the medieval market town, where old storefronts crowd around a busy square. Medieval and 18thcentury bridges link the peninsula with the lands across the river, and the riverbanks are lined with forests and paths.

It wasn’t built to be beautiful, however. Durham was founded as the great fortress of the North, and ruled as a nearly independent state by its powerful prince bishops. Its story is one of violence and power, and everything you see when you visit Durham today comes out of that story.

Modern day Durham has two parts: the peninsula and everything else. On the peninsula, everything is old (excluding a parking garage tucked into a corner); even the Victorian storefronts are facades placed on 17th- and 18th-century homes. Off the peninsula, everything is new; except for a small group of 18th-century buildings at the end of each of the two medieval bridges, the rest of the town is Victorian or modern. The two areas are kept apart by a modern four-lane highway, the A690, running across the peninsula in a deep trench at its top end. When the highway was conceived in 1944, the town intended to sell air rights above its trench, creating continuous retail between the old town and the new. Seventy-five years later, that’s still the plan. Meanwhile, the A690 acts as a castle moat, protecting the old town from modernist barbarians.

Durham is not (by English standards) an ancient town. The monks of St. Cuthbert created it in 995, quite intentionally, as a strongly fortified refuge and place of safekeeping for their saint’s relics. St. Cuthbert was a 7th-century abbot at Lindisfarne, an island 65 miles north, whose body never rotted; this was seen as a miracle, and the uncorrupted body was believed to have healing powers. In the medieval world, saints’ relics with healing powers could be readily monetized—but only if pilgrims weren’t afraid of being slain by Viking raiders. By the 9th century, Viking raids had become a fearsome threat and the monks of St. Cuthbert started looking for a safer refuge. Not only was the cliff-sided river loop at Durham perfect, but the Earl of Northumberland also was willing to grant it and the surrounding lands to the monastery. It worked; during its first 60 years the new monastery was attacked only once by Danes and twice by Scots, all to no avail.

Then the Normans, an altogether tougher group, came to Northumberland. Since St. Cuthbert’s day, Northumberland had fallen from being the richest and most powerful of the independent English kingdoms, to becoming a Viking vassalage. It finally entered the kingdom of England in 920, its king demoted to an earl who did homage to the heirs of Alfred the Great. In 1066 William the Conqueror declared himself the heir of Alfred, but neither the Earl of Northumberland nor his people bought in. To them, the Normans were just another bunch of foreign invaders.

When William appointed a new Earl of Northumberland in 1069, he was promptly murdered. William’s next appointment marched northward with 700 men—and locals murdered him, too, burning him to death in a house in Durham and slaughtering his troops. William’s response was the genocidal “Harrying of the North.” Contemporary scholar Oderic Vitalis wrote: “He made no effort to control his fury and he punished the innocent with the guilty. He ordered that crops and herds, tools and food should be burned to ashes. More than 100,000 people perished of hunger. I can say nothing good about this brutal slaughter. God will punish him.”

During this the Bishop of Durham had sided with the resistance, and had died in prison as a result. In 1071 William appointed a trusted Norman retainer, William Walcher, as the new bishop, and a Saxon noble as Earl of Northumberland. Four years later, the Saxon earl rebelled and was executed—and Walcher became earl as well as bishop, the first of the prince bishops who would rule Durham as an independent state for the next five centuries.

Walcher laid plans to modernize the Saxon fortress with the latest Norman technology. He dug a dry moat across the peninsula’s narrowest point, and on the south side of this he built a large mound with a tower on top, a motte, and enclosed a fortified range between this and the river, a bailey. The motte-and-bailey castle would serve as his seat of worldly power as earl and his seat of heavenly power as bishop—a palace as well as a castle. To its south he planned to build a cathedral, and then place the castle garrison in a second, outer, bailey south of that. Walls would encircle the entire complex, running along the top of the cliffs to form a massive fortress. Merchants and craftsmen would live just outside the castle under its northern walls, on the unprotected landward side of the peninsula. Walcher’s 11th-century plan remains the layout we see today.

BISHOP WALCHER NEVER GOT TO START his cathedral however, having been murdered in 1080 in yet another rebellion. William de St. Calais, Walcher’s replacement, set about completing his plans—but got on the wrong side of the king in 1088 and fled to Normandy. When Bishop St. Calais returned in 1091 he had grand new plans, inspired by the cathedrals he had seen in France. St. Calais completely changed Walcher’s more modest designs to create one of the grandest cathedrals in Europe, still today one of England’s most intact examples of Norman design.

‘Durham is not by English standards an ancient town. The monks of St. Cuthbert founded it in 995’

[caption id="DurhamofthePrinceBishops_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

The Normans pioneered the massive, tall stone church pierced with large windows, adapting Roman techniques they had observed on the continent. The columns are massive, and deeply incised with abstract designs; windows are tall and skinny, recessed within the huge piers needed to support the roof. And that roof is state of the art for the 1090s—not the timber span found in earlier churches, but stone vaults floating outward from the piers. St. Calais placed the main entrance on the northwest side, immediately opposite his palace-castle, allowing a grand procession as he traveled from his temporal seat to his spiritual seat. He placed the priory on the south side, where monastic buildings still surround a cloister. Only the east and west ends of the cathedral are later expansions.

If the cathedral is little changed from its 11th-century design, the castle represents every period from the 11th to the 19th. It had to reflect the material power of the earldom as well as the spiritual power of the bishop, in ways both symbolic and practical—particularly as the Scots continued to attack it deep into the 17th century and actually managed to annex it for a few years in the mid-12th century. This was a working fortress with a permanent garrison, and each prince bishop had to find his own compromise between his desire for status and comfort and his need to live surrounded by soldiers. Starting at least with St. Calais, the bishops lived not in the tower (which became a fortified refuge of last resort), but in halls that lined the bailey adjacent to it, and these were torn down and rebuilt multiple times. What we see today is an amalgam from early medieval to Regency.

SO WHERE DID THE PRINCE BISHOPS get all that stone? Hauling stone is expensive, and hauling it across a river even more so. The answer turns out to be simple: They got it from the cliffs beneath the walls. Today there is a narrow shelf following the riverbank, and the slopes above it are steep but seldom precipitous. That’s because the bishops cut the original cliffs into stone and winched it upward to build the castle and cathedral.

When quarrying ended, the slopes were kept completely clear of trees so that the castle garrison would have open fields of fire from the walls. On the downstream (northwest) side would have been a series of weirs, both to provide power for mills and to keep the river deep enough in dry weather to prevent attackers from simply wading across; 18th-century weirs and mills now mark the locations of their medieval predecessors. As time wore on, the prince bishops felt secure enough to build stone bridges over the river, one on each side of the town. This was not an act of charity; the bishops owned the town as well as the mills, and profited from its market.

The prince bishops stood between a peaceful England and the wild North. Of course, England wasn’t that peaceful, but there was a real difference between the normal round of medieval warfare and an invasion of wild Scots; the presence of the prince bishops gave the English king enough safety to get on with his endless quarrels with his relatives. In return for keeping the kingdom safe from invasion, the prince bishops wrote their own laws, enforced them in their own courts, held their own parliaments, led their own armies, minted coins and basically owned everything in sight. The prince bishops were frequently the most powerful men in the kingdom after the king himself, and included the likes of Thomas Langley and Cardinal Wolsey. Best of all (from the king’s point of view), because the prince bishops were officially celibate, they couldn’t pass any of their power to a trouble-making son. Once a prince bishop died, the king got to appoint a new one. All in all, it was a good arrangement.

[caption id="DurhamofthePrinceBishops_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

‘Durham Cathedral remains today one of England’s most intact examples of Norman design’

It was Henry VIII who messed it up. Henry wanted to establish a strong central government, and to do this he set about suppressing the medieval church and the medieval distribution of feudal power; we call it the Reformation. In 1536 he stripped the prince bishop of many of his temporal powers, and three years later dissolved the monastery. For the first few years the new order respected the old ways, but later deans (who replaced the prior) were fire-breathing Puritans who heavily vandalized the cathedral—and angered the locals into yet another rebellion. Nor was Durham yet safe from invasion; during the English Civil War a Scottish army seized it twice. Durham’s woes didn’t end there. During the Interregnum, Cromwell eliminated the bishopric and converted the cathedral into a prisoner of war camp; during the winter’s cold, Scottish prisoners ripped up the medieval wood carvings and burnt them to keep warm. And so the prince bishops came to an end.

Except they didn’t. In 1660 Cromwell died, and Charles II was restored to the throne—and the bishopric was reinstated along with its lands and its temporal powers. The new bishop, an old Royalist returned from exile named John Cosin, set about restoring the cathedral and rebuilding the castle into a proper modern residence. Despite his long stay on the continent, Bishop Cosin turned to local carpenters and masons, leading to a delightful mix of old and new styles that represent the period vernacular at its best. Cosin and his craftsmen dismantled Fortress Durham, and in its place built parks and gardens, elegant townhouses and compact stone cottages. Cosin, more than anyone else, created the landscape inside the walls that remains today. Durham grew throughout the 18th century, but slowly and in place. This was largely the bishop’s doing; the prince bishops still owned all the land. Development consisted of replacing wood with stone, chopping big stone buildings into smaller ones, and subdividing the long, unused burgage plots that strung out behind the house fronts. Narrow pedestrian alleyways known as “vennels” gave access to these rear plots, and a number of them exist to this day. If you visited the Durham peninsula in 1830 most of it would pretty much look like it does now, only dirtier—sewers were still in the future.

Big changes came in 1832. In that year Parliament passed the Reform Act, eliminating the hodge-podge of surviving medieval governance throughout the nation and replacing it with democratic institutions. The prince bishop was now just a bishop. The Bishop of Durham moved out of the castle to Bishops Aukland 10 miles south, and gave the castle to the newly established University of Durham, whose University College still occupies it. It is the university that built the octagonal building that now sits at the top of the motte, the old medieval tower having long since fallen into ruin. By 1860 a new public health authority had declared the old town to be overcrowded and stopped issuing new water and sewer permits, effectively freezing it in its Regency appearance. It remains there still.

WHEN YOU VISIT DURHAM TODAY, park in that modern garage on its northeast corner and walk slowly down the peninsula. Enjoy the shops, take the tour through the castle and then wander freely through the magnificent cathedral. Walk through the Outer Bailey, now crowded with 17th-and 18th-century townhouses, then follow the wooded footpaths along the river, past weirs, mills and old stone bridges. And, as you enjoy this unspoiled historic center, contemplate that all its beauty was brought about by centuries of violence and war.

Comments