What Britain Brought Home from Colonial India.

When you use English, you can hear an echo of the Raj in every sentence. The resonances of India in the UK extend far beyond the takeaway food counter. The British Raj bowed out over two days in 1947. That summer, British control over Indian affairs ended, under the watch of the last Viceroy of India, war-time hero Lord Louis Mountbatten of Burma, and British India was carved into two separate, independent states, Pakistan and India.

The first Indian prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, decreed that, to spare British feelings, there would be no formal lowering of the Union flag. Instead, the new Indian flag would be raised at 6 p.m. in Delhi on August 15, 1947, before a formal dinner enjoyed by former colonialists and subjects.

The formal British Raj, or “reign” in Hindi, lasted barely 90 years, ending with Mountbatten’s salute on that steamy August evening—though the British presence in the vast subcontinent extended back beyond the creation of the United Kingdom. In 1600, just 12 years after the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the English Parliament granted the East India Company a charter to trade with India. The Company’s rule ended when London grabbed political control of the country after the Indian Mutiny in 1858, putting in place a Viceroy, and creating the Raj that would end 89 years later.

Language lessons

This relationship was not a one-way street. Up to 7,000 Indian students, seamen, servants, politicians, and intellectuals were recorded in Britain by the 1930s. These people, and the Britons who returned from India, brought with them words from Hindi and the other main subcontinent languages that are common wherever English is spoken. The linguistic impact shows up in a sample of common words—avatar, bottle, candy, dinghy, loot, mantra, polo, pyjamas, and shampoo—that have taken up residence in the language of the former rulers.

There is also an informal legacy in phrases that are still in use in Britain: “Let’s have a dekko” is to take a look at an object; to go “Doolally” is to lose one’s mind, after the British Army’s hospital at Deolali where patients were said to go mad with boredom; “I don’t give a damn” derives from the Indian coin Damn, which was of little value. A British 18-wheeler is colloquially known as a “juggernaut,” a borrowing from Hindi and a metaphorical reference to the enormous Hindu Ratha Yatra temple car, which apocryphally crushed devotees under its wheels.

Celebrated playwright Tom Stoppard explored Anglo-India themes during the Raj in his 1995 play India Ink, which had an American premiere in 1999 at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. In the play, two characters compete to use as many Indian words as possible in an English sentence. “While having tiffin on the verandah of my bungalow I spilled kedgeree on my dungarees and had to go to the gymkhana in my pyjamas looking like a coolie,” was the challenge. In reply, the second character sharply ripostes: “I was buying chutney in the bazaar when a thug who had escaped from the chokey ran amok and killed a box-wallah for his loot, creating a hullabaloo and landing himself in the mulligatawny.”

Bungalows and verandahs

Bricks and mortar in Britain also echo the Raj. Visitors to Britain can enjoy a splendid range of grand country houses and destinations that still have a whiff of the subcontinent about them and sometimes a very racy past.

Britons went to India as traders in the 17th century, and as traders and soldiers in the early 18th century. Traders sailed with the idea of making their fortune in India by becoming a “nabob.” From the Hindi nawab, the nabobs knew how to do it. Make your fortune in the Wild East and return to England to buy your way into the land-owning class, thus becoming the ultimate nouveau riche.

Buy a rotten borough to become a member of parliament. Then build a stately home.

While ordinary British folk reside in a bungalow, often with a verandah—itself a building style brought from India—the nabobs built splendid accommodations that British Heritage readers can enjoy to this day.

Basildon House (National Trust), near Reading, considered an outstanding Neo-Palladian architectural fantasy, was built between 1776 and 1783 for Francis Sykes, son of a modestly prosperous Yorkshire yeoman farmer who rose to become immensely powerful in Bengal. He returned to England in 1769 with a fortune of half a million pounds, worth by some estimates £55 million today.

Architectural critics say that every detail of Basildon, from the plant pots and statues in the extensive gardens to Doric facades and internal plasterwork, reinforces the classicizing illusion of influence that Sykes wanted to buy. His rise to a Baronetcy in 1781 brought him at last into the aristocracy of the land-owning gentry.

So many of these nabobs settled in Berkshire, near Basildon House, that the area was quickly dubbed the English “Hindoostan.” Some 30 such houses associated with nabobs were built in the county, a number of which can be visited today, three centuries after many were constructed. Shottesbrooke is now a private residence but may be seen from the adjoining churchyard on which there is public access. Swallowfield Park is now divided into private apartments while the gardens of Englefield House are open to visitors during the summer.

Go West for the East

Gloucestershire ended with a series of stunning houses made for nabobs on their return from the “Jewel in the Crown.” It also, curiously, has a small cottage in Lower Swell in the “Hindoo” fashion.

The stately home to visit is Sezincote House, Gloucestershire. Pronounced Seezin-kt, the house is an extraordinary fantasy of India amidst the Cotswold Hills. Designed in 1810 by Samuel Pepys Cockerell in the Neo-Mughal architectural style, Sezincote is credited with being a reinterpretation of 16th- and 17th-century architecture from the Mughal Empire and the direct inspiration for another Indian fantasy, the Prince Regent’s Brighton Pavilion.

Nearby is Daylesford House. Built in 1788, it was acquired by Warren Hastings, governor-general of India. Remodeled by Samuel Pepys Cockerell, with magnificent classical and Indian decoration, the gardens were landscaped by John Davenport. There is a popular farm shop on the estate, which sells organic food under the Daylesford Organic brand.

CREDIT: JOE WAINWRIGHT/ALAMY

On the south coast, the confection of Brighton’s Royal Pavilion gave the nabobs the ultimate seal of approval. They had arrived, even if the local population must have been absolutely confounded as a humble farmhouse was turned into an image of an Indian palace on their doorstep. In a neat twist of history, John Nash’s extraordinary oriental fantasy built for George, the Prince Regent, housed wounded Indian soldiers in World War I during the reign of George V. It was felt the atmosphere would make the troops feel at home.

The Paisley pattern is wrongly attributed to the Scottish city of the same name. In fact, it came from India and not surprisingly Paisley Museum, Scotland’s first municipal museum, has the finest collection of Paisley shawls in the world. Not surprisingly, too, shawl is an Indian word.

If the Raj can ever be said to have had a headquarters, then the India Office in London was where real political power resided. First used in 1867, and now part of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the India Office building is at the heart of the Foreign Office.

Its Durbar Court, a sumptuous Victorian courtyard, was designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott and Matthew Digby Wyatt in the classical style, with Doric, Ionic and Corinthian columns and an elaborate marble floor.

SAY IT IN HINDI

50 words from India that have taken up residence in England: atoll, avatar, bandana, bangle, bazaar, blighty, bungalow, cashmere, catamaran, char, cheroot, cheetah, chintz, chit, chokey, chutney, cot, cummerbund, curry, dinghy, doolally, dungarees, guru, gymkhana, hullabaloo, jodhpur, jungle, juggernaut, jute, khaki, kedgeree, loot, nirvana, pariah, pashmina, polo, pukka, pundit, purdah, pyjamas, sari, shampoo, shawl, swastika, teak, thug, toddy, typhoon, veranda and yoga

Taste of India

It is not just the language and bricks and mortar that echo the Raj. Glasses and plates all over the country recall the Raj. The oldest surviving Indian restaurant in the UK, Veeraswamy, is located at 99-101 Regent Street. It was opened in 1926 by Edward Palmer, the great-grandson of an English soldier and an Indian princess.

The Twinings Museum, exactly opposite the Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand, is the perfect place to buy Indian tea in the capital. If there is any question as to the merchant’s heritage, Thomas Twining sold tea to King Charles II.

©MALCOLM MCHUGH/ALAMY

While there are obvious Indian foods that have found their way across the thousands of miles between the two countries, such as curry, rice and kedgeree, there are two foods essential to the British diet that seem British, but owe their heritage to the Raj.

Worcestershire sauce is the quintessential British condiment, yet arrived from India in the 1830s. Originally made by two dispensing chemists, John Wheeley Lea and William Perrins, in Worcester, the sauce was modeled on a recipe brought from India and first offered for sale in 1837.

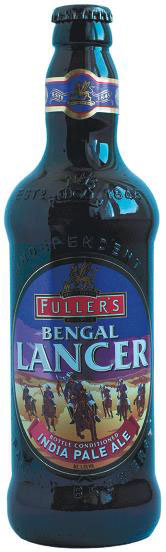

At the bar, order a pint of IPA (India Pale Ale) and you will be drinking a little bit of history. First brewed in London in the 19th century, the beer was created especially to survive the six-month sea voyage to India, where it was consumed by Britons keen to slate their thirsts.

Look out for Fuller’s Bengal Lancer, pale in color, full-bodied with a distinctive hoppiness. The Bengal Lancers, immortalized in folklore, novels and on the Hollywood screen, have their origins in the 1700s when the nawab of Awadh, in today’s northern India, raised Bengal’s first regiments of cavalry.

Another British favorite, the Gin & Tonic or G&T, came about in colonial India, when the British population would mix their medicinal quinine tonic with gin to improve its bitter flavor.

On the sporting field, the British took cricket to India, and polo came back in exchange. A diverse range of people enjoy the sport. Watch a polo match and you could easily find yourself rubbing shoulders with royalty, supermodels, and stars of the stage and television at around 50 polo grounds dotting the English countryside.

The Raj formally ended a lifetime ago, yet echoes remain throughout Britain. Just over a decade ago, the Memorial Gates war memorial was unveiled at the Hyde Park Corner end of Constitution Hill in London. The monument commemorates the armed forces of the British Empire from five regions of the Indian subcontinent—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka—who served Britain in World Wars I and II.

Perhaps more than words or food, that is the true echo of the Raj in Britain.

* Originally published in 2016. Updated in 2023.

Comments