AS TENSIONS BETWEEN PARLIAMENT AND THE CROWN HEATED TOWARD WHAT BECAME THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR, DISSENTING PURITANS IN THE EASTERN COUNTIES SOUGHT REFUGE FROM ECONOMIC HARDSHIP AND RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION. TO THE SHORES OF MASSACHUSETTS BAY THEY BROUGHT THEIR SPIRITUAL IDEALS AND WAY OF LIFE.

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponAHill_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Primedia Archive

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img1" align="aligncenter" width="197"]

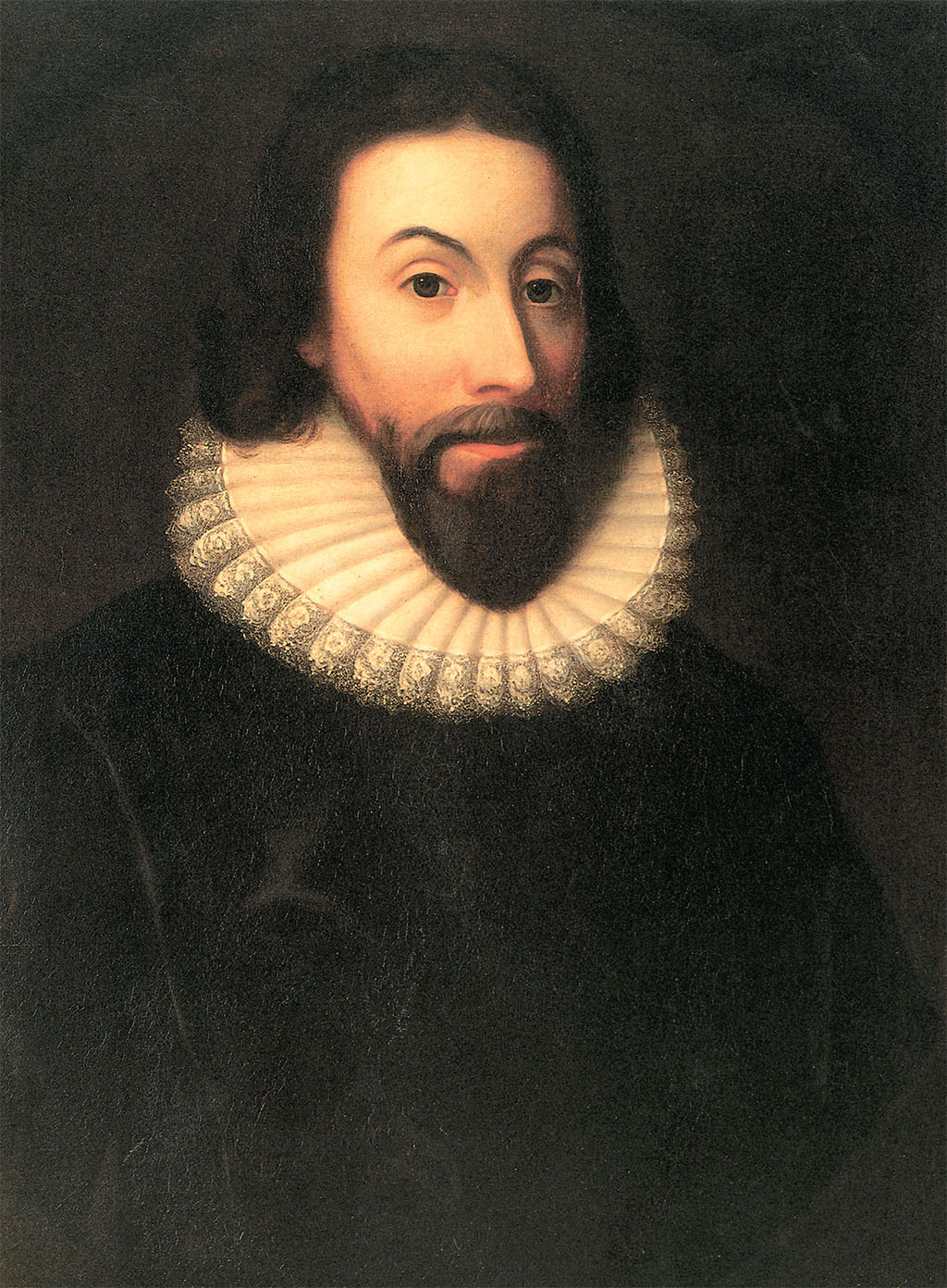

In 1618 John Winthrop could count himself among England’s fortunate. He married Margaret Tyndal, the woman he was to call “mine owne, mine onely, my best beloved,” and he inherited his father’s estates, becoming Lord of the Manor in Groton, Suffolk. Born 30 years earlier, he had survived the high childhood mortality rates of his era and was to live another 31 years. He was already an esteemed country justice. With a thriving professional life, estates in one of the richest parts of England and a family of children born during two previous marriages to wealthy heiresses, Winthrop occupied a comfortably cushioned niche in society. Only 12 years later, however, and despite having won a royal legal appointment, he left England, taking himself and two of his sons, 9-year-old Adam and 10-year-old Stephen, across the Atlantic to an uncertain future on the rocky shores of Massachusetts.

Why? As the ship Arbella battled the waves, he told its passengers, “We must consider that we shall be as a City upon a Hill so that if we deal falsely with our God in this work…we shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the way of God.” But how had it come to pass that these serious citizens were leaving England for a distant continent whence most would not return?

The answers are many. Economically, times were bad. Wars in Europe had halved the markets for the Suffolk shortcloths (knee breeches)—one of the main economic supports of Winthrop’s county. Charles I was on the throne and, like his father James I, he raised money by selling monopolies that inflated the prices of many basic commodities. With a growing brood, Winthrop was not alone in thinking he might do better overseas. Many English families were emigrating to Ireland and the Caribbean as well as to America. Like them, Winthrop, who had lots of practical experience, probably foresaw economic benefits to be gained overseas. As his shipboard exhortation shows, though, his most powerful motives for leaving England—and instructing his eldest son to sell the manor house at Groton and follow him across the ocean—were religious. Winthrop and his fellow passengers were Puritans, and for Puritans life in England was especially hard.

Their problems were rooted in 16th-century religious controversies. Led by Martin Luther, John Calvin and Ulrich Zwingli, early 16th-century European theologians set out to reform the church, questioning such doctrines as the real presence of Christ at the Mass and protesting such abuses as the sale of pardons, the levying of church taxes and the lax habits of its monks and priests. In England Henry VIII, flush with imperial notions and eager to divorce Catherine of Aragon so he could marry Anne Boleyn, was easily persuaded that he, not the pope, was head of the English church; by 1532 he had insisted on a Submission of the Clergy that forced most priests to agree. In 1536 he went further, expropriating monastic lands and properties to boost his treasury or reward his courtiers.

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img2" align="aligncenter" width="483"]

THEY STRIVED TO CREATE A CHURCH AND TO LIVE LIVES THAT SHONE WITH THE SPIRITUALITY OF EARLY CHRISTIANITY. FROM THESE BELIEFS, THEY TOOK THE NAME PURITAN.

Archbishop Cranmer encouraged Henry’s supremacist policies, but Henry never abandoned Catholicism. Cranmer was more successful with his son Edward VI, who became king in 1547. Under Cranmer’s tutelage, Edward banned cults of saints and customs such as blessing candles at Candlemass, or releasing doves from St. Paul’s Cathedral at Whitsuntide. Church music was forbidden and church paintings were obliterated. Cranmer had long been secretly married; now all priests could marry. English replaced Latin as the language of church services, and everyone—not just priests—was encouraged to read one of the new translations of the Bible.

Describing “the exhilarating appeal of Protestantism,” historian Simon Schama notes, “If there was destruction of false gods and idols, it was only so that the purity of gospel truth could be brilliantly revealed.”

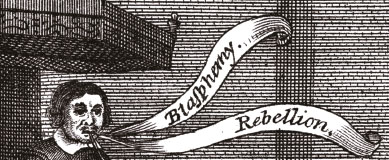

The idea of “purity” is central to the religious debates of the era and especially to the beliefs of Winthrop and other passengers on Arbella. They strived to create a church and to live lives that shone with the spirituality of early Christianity. From these beliefs, they took the name Puritan.

But how pure was pure enough? Many Protestants happily abandoned the supremacy of the pope and the obscurity of the Latin service, but still loved gorgeous vestments, painted churches and the traditional sacraments. On the other hand, as theologians explored the Scriptures, radical Puritan ideas emerged. Doctrinally, they replaced the belief that grace was won by good works and repentance with the sterner notion that it was given by God only to those predestined to receive it. Puritans also believed in the inherent depravity of humankind and, like other Protestants, rejected the idea that Christian truth could only be approached through a priest. Indeed, personal encounter with the Scriptures was central to Puritan faith.

Possibly Winthrop and his peers would have lived contentedly in the Protestant regime of Edward VI, but in 1553 his half-sister Mary, the daughter of Catherine of Aragon, succeeded him. Mary was a fervent Catholic who repealed all of Edward’s religious laws, returned England to the authority of the pope and arrested and eventually burned Cranmer along with nearly 300 other Protestants. Some saved themselves from the flames by fleeing to Holland or Geneva, where they immersed themselves in Calvinist doctrine.

When Henry’s second daughter, the Protestant Elizabeth, became queen in 1558 she stopped the burnings. While she favored a celibate clergy, she tolerated leeway and permitted individuals to guide their flocks in many ways—not, however, through the Church of Rome. Catholic priests trained on the Continent smuggled themselves into England at great risk. Equally, Puritan scholars persecuted during Mary’s regime were not always entirely welcome to Elizabeth’s archbishops. Ironically, then, Elizabeth’s relatively tolerant policies polarized many churchgoers. Controversy continued under the Stuart kings, James I and Charles I, who followed Elizabeth in promoting a moderate English church that supported a hierarchy of bishops, an ornate liturgy and the efficacy of the sacraments.

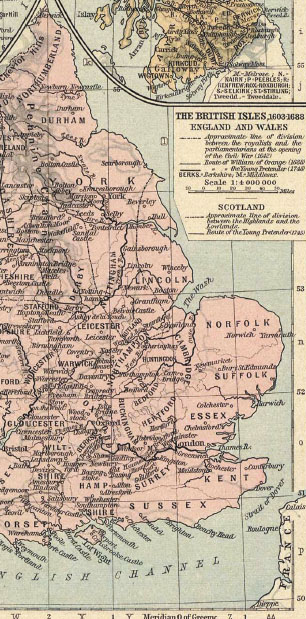

Thus for the English, a range of belief was possible, and different regions of the country tended to favor different doctrines. Puritans were especially numerous in East Anglia, which included Winthrop’s county of Suffolk along with Norfolk, Essex, Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire. It was the richest region of England, with good agricultural land, excellent fisheries, a well-established cloth-making industry and many small towns such as Cambridge, then a center for Puritan theology, and urban Norwich, which was probably England’s largest city after London. Ports dot its long curving coast and, in an era when roads were often impassably muddy, these gave the region easy links to London and to Holland, just across the North Sea.

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img3" align="aligncenter" width="306"]

University of Texas, Perry Casaneda Library Map Collection

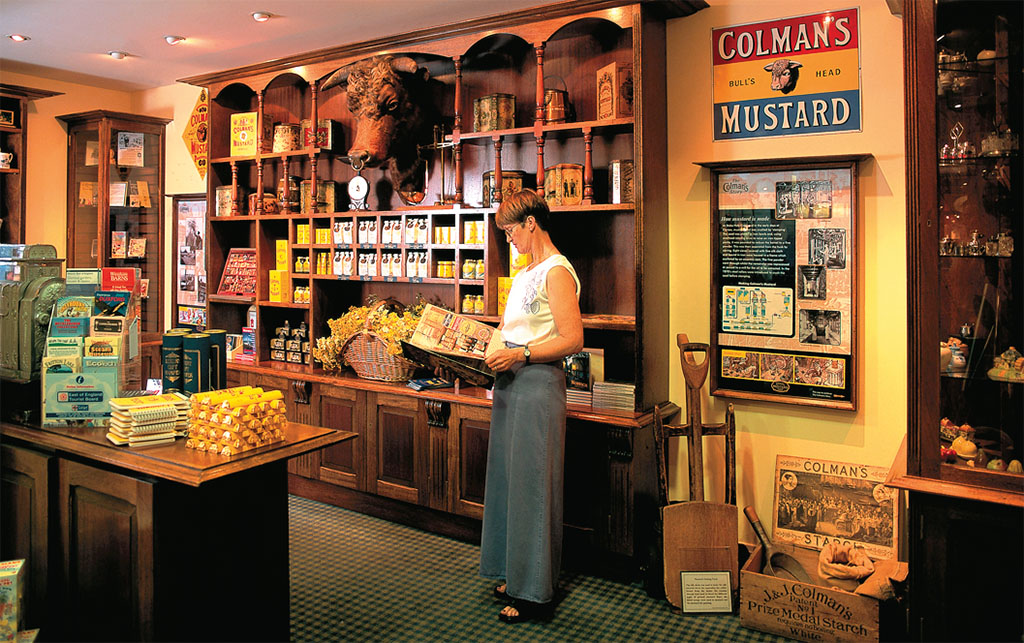

East Anglians raised large numbers of turkeys, geese, chickens and ducks in Norfolk and Suffolk. They fattened beef and grew mustard—England’s favorite condiment for serving with it. Hops for beer-making flourished in Suffolk, and saffron for dyeing cloth and flavoring traditional holiday cakes and breads grew around Saffron Walden in Essex. Like the cloth woven from local wool and the flsh caught in the teeming North Sea, these products were easily shipped to London markets from East Anglia’s ports.

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img4" align="aligncenter" width="389"]

THE GRANGER COLLECTION,NEW YORK

People could also easily get to London. John Winthrop studied and practiced law there, and honed his enthusiasm for a New World by witnessing the evils of the city. Other Puritans also found much to dislike. Lucy Hutchinson described the court as “a nursery of lust and intemperance” and raged against “proud encroaching priests” and “lewd nobility.” Even the poet Ben Jonson, who served the court as masque-maker, derided the times as a “money-get mechanic age.”

Yet, if the greed and immorality of London inspired Puritan religious austerity, its opportunities filled their money chests and fueled their confidence. As the English grew more disaffected with the Stuart court, London became a center of Puritanism and of opposition to the extravagances of Charles I, with East Anglia as its rural counterpart. Puritan teaching about the importance of personal salvation and the centrality of reading the Bible had a secular analogue in ideals about work as a sacred calling, the idleness of the nobility as a sin and the rights of property owners to determine the laws of the country.

This did not mean that John Winthrop and his fellow Puritans were democrats; Winthrop described democracy as “the meanest and worst of all forms of government.” The passengers on Arbella did not include any of the poor and huddled masses of London and East Anglia. The ship was named after Lady Arbella Fiennes, sister of the Earl of Lincoln, who was a passenger. With her were her brother, Charles; her friend, the poet Anne Dudley Bradstreet, who had grown up in the earl’s household; and two of the earl’s stewards, Simon Bradstreet and Thomas Dudley. Along with them were numerous members of the landowning gentry, clergymen, merchants, farmers and skilled tradespeople such as weavers, tailors, shoemakers and carpenters.

Less than 5 percent were laborers. This was the result of deliberate policy. Dudley had advised recruiting only “godly men…endowed with grace and furnished with means,” while Winthrop, who became governor of Massachusetts, told his son John—later governor of Connecticut—not to allow people of “the poorer sort” to come to America. “People must come well provided, and not too many at once,” he wrote. In all, 17 ships packed with Puritan immigrants traveled the ocean in 1630. By 1641, 200 ships had arrived with around 21,000 immigrants. Among them were 129 clergymen and theologians with strong connections to Cambridge University, especially Emmanuel College, where a third of them had studied; and to East Anglia, where many had held parishes or had family connections.

As historian David Hackett Fischer explains in Albion’s Seed, Massachusetts immigrants were atypical, and not just in their religious faith and material prosperity. “To a remarkable degree,” he wrote, “the founders of Massachusetts traveled in families—more so than any ethnic group in American history.” Thus, while immigrant groups elsewhere were made up mostly of young, single men, in Massachusetts 40 percent of newcomers were mature adults, many with children. Noting that more women than men fulfilled the stringent requirements for church membership, Fischer points out that “It would be…statistically correct to say that many Puritans led their husbands to America.”

From the beginning, then, life in Massachusetts was domestic, often following familiar English patterns with accommodations to Puritan beliefs. People typically married in their mid-20s, but while a quarter of English people never found the wherewithal to marry, virtually all New Englanders married, since failure to find a spouse suggested the withdrawal of divine grace. Marriage was not an indissoluble sacrament as it was in England, but a legal contract breakable by divorce—a Dutch idea that William Bradstreet described as “the laudable custom of the low countries,” where so many Puritans had taken refuge. Couples could not marry without their parents’ consent, but parents could not will fully withhold permission.

Contrary to stereotype, the Puritans were not joyless; love and sexuality were central to marriage, though unlicensed sexuality was disapproved of. Similarly, Puritans abhorred drunkenness but were delighted to find grapes growing wild in the New World because they enjoyed wine. They liked food, too, and they brought with them the East Anglian tradition of baking. While they dressed in browns and grays, they approved of the English idea that community leaders should denote their status by finer clothes. As for festivity, they loathed the rambunctiousness of the English Christmas because it was a religious occasion, but they had many thanksgivings when games and feasting were the order of the day.

BY 1641, 200 SHIPS HAD ARRIVED WITH AROUND 21,000 I M MIGRANTS, 129 OF THEM CLERGYMEN AND THEOLOGIANS.

Many families were related before they left England, and after they arrived they intermarried, creating an oligarchy of prominent families with names such as Winthrop, Dudley, Mather, Saltonstall, Hutchinson and Davenport. The children of clergymen tended to marry each other, and a clerical elite was perpetuated over generations, as, for example, Cotton Mather followed his father Increase Mather and his grandfathers Richard Mather and John Cotton into the ministry.

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE GRANGEER COLLECTION,NEW YORK

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img6" align="aligncenter" width="721"]

PRIMEDIA ARCHIVE

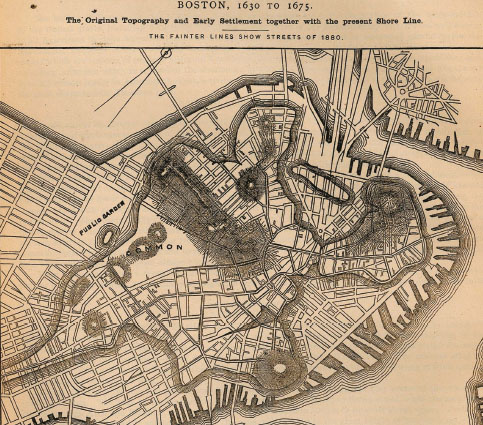

Large families were typical, and groups of families quickly spread beyond the coastal settlements, creating towns named after places they had known in England. The port cities of Boston, Hull and Lynn recall the major ports of eastern England. Thirty-six towns in all were named after English towns, at least 20 of which were in East Anglia. Later towns such as Winthrop, Dudley and Leverett were named after Puritan leaders, while Milton commemorates the English Puritan poet John Milton.

Massachusetts also developed an economy similar to that of East Anglia. Unlike many New World economies based on mines or plantations, it depended on fishing, agriculture and trading. As early as 1645, the towns of the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts were shipping thousands of bushels of grain. Like 17th-century England, which Peter Laslett described as “a large rural hinterland attached to a vast metropolis” of London, Massachusetts quickly became a region of farming villages served by small seaports attached to the metropolis of Boston.

With all its freedom from the license, laxity and oppression of England, Massachusetts did not suit everybody who went there. The early days of living in tents and huts were harsh. Massachusetts is a rainier climate than East Anglia, and its winters much colder. Lady Arbella’s husband Isaac Johnson noted that things were “dolorous” at first, and many regretted their “voluntary banishment.” When the immigrant ships sailed for England, hundreds of would-be settlers returned home. Those who did not fit in with the Puritan social order were sent to other colonies or back to Britain. In 1641, when the English Civil War began, some immigrants returned to fight on the Puritan side, and when the Puritans won, many resumed English life under Oliver Cromwell’s more congenial Puritan sway. Of these, Hugh Peter, minister of Salem and a founder of Harvard University, was executed for his wartime activities when Charles II regained the Stuart throne in 1660.

But returnees were a minority. Most immigrants used their funds and their energies to make prosperous lives, creating a New England that wove East Anglian habits, Puritan convictions and North American contingencies into a vibrant cultural tapestry, distinctly American, yet still recognizably English in its underpinnings.

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img7" align="aligncenter" width="527"]

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img8" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img9" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img10" align="aligncenter" width="628"]

[caption id="FromEastAngliatoACityUponaHill_img11" align="aligncenter" width="370"]

Comments