‘And the glory, the glory of the Lord shall be revealed’

Nothing like this epic work with its tremendous scope had ever been done before

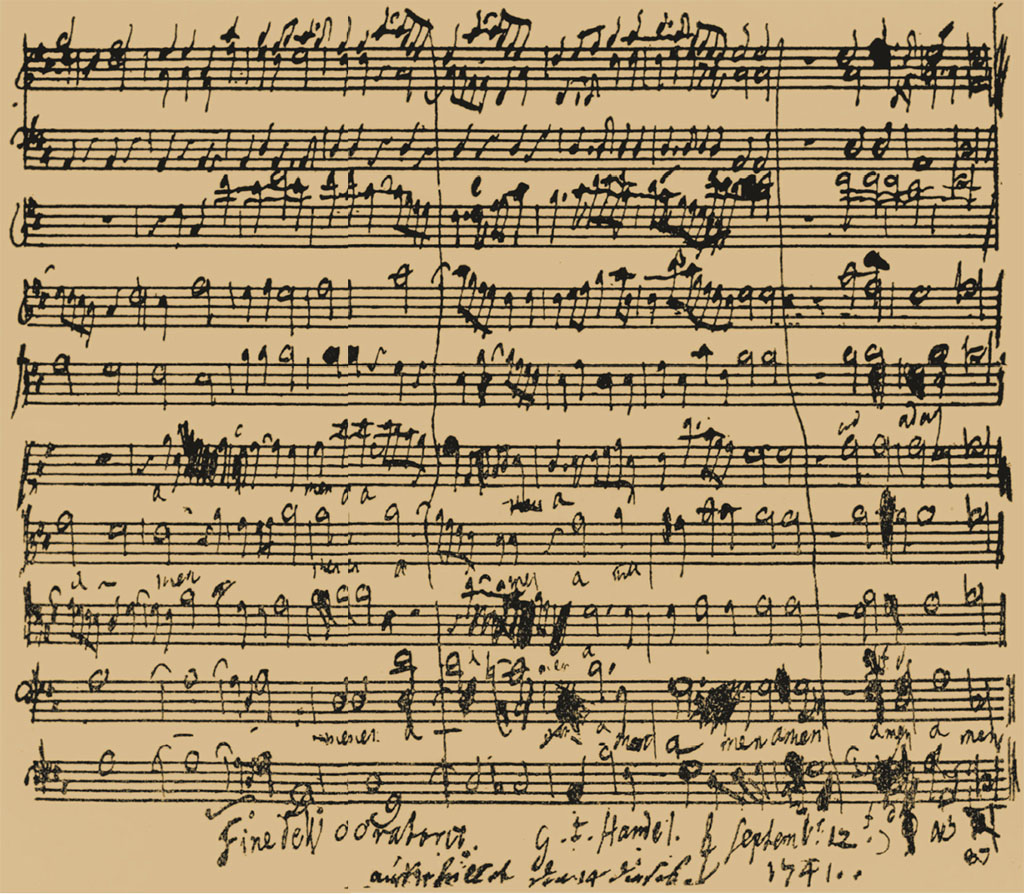

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PRIVATE COLLECTION/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

George Frideric Handel’s Messiah, more than any other piece of classical music, is associated with Christmas, though the composer himself identified it more with the season of Lent and Easter. Its subject matter seems very fitting for the Easter season, and the Royal Albert Hall has been presenting it on the afternoon of Good Friday every year for the past 150 years. The Albert also ensures that it is on the Christmas schedule.

It was on August 22, 1741, that Handel, who was 56 years old at the time, sat down in his London home at 25 Brook St. in the neighborhood of Mayfair to start work on Messiah, which was to become one of his best-loved and best-known classical compositions. His friend Charles Jennens, a literary scholar and editor of William Shakespeare’s plays, had the idea of writing a sacred oratorio called Messiah that would be performed during Passion Week. Jennens wrote the libretto using actual language from the Old and New Testaments. He drew from the Gospels, Epistles, Psalms and Isaiah, as well as lesser-known parts of the Bible.

Handel completed the musical score for Messiah in just 24 days, rarely leaving his room or stopping to eat. The oratorio was finished on September 14, though he was to revise it over the course of the next eight years. Alas, Jennens was rather annoyed with Handel, as he felt that more time should have been given to his libretto and that Handel should not have rushed the composition of the score the way he did. In a letter, Jennens wrote about Handel and Messiah that “he has made a fine entertainment of it, though not near so good as he might and ought to have done.”

That was Handel’s working style, however. He usually toiled at a rapid pace. Within days of completing Messiah, he was busy again composing another oratorio, Samson. He completed Samson in one month, working on it from September 29 to October 29, 1741.

Handel always paid proper tribute to Jennens for his extraordinary contribution to the work and often referred to it as “your Messiah” or “your oratorio” when writing or talking to him. A popular misconception is that the work is called The Messiah, but Handel titled it simply Messiah.

While Messiah was quite successful at its world premiere at the Fishamble Street Musick Hall in Dublin, Ireland, on April 13, 1742, it received a rather lukewarm reception when it was first performed in London at the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden on March 23, 1743. The London premiere of the piece was not advertised with its title but as “A New Sacred Oratorio,” because it was considered too risky to present such a sacred subject matter in a London theater.

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_img1" align="alignright" width="1024"]

In 1750 Handel conducted the first charity performance of Messiah for the Foundling Hospital in Lamb’s Conduit Fields, where he also was elected a governor that year. With the initial performance at the Foundling Hospital, Messiah became deeply associated with that charitable organization and also very popular with the public. Thereafter Handel conducted Messiah annually in the hospital’s chapel. He provided in his will that the hospital should continue to benefit from the work after his death and bequeathed “a fair copy of the Score and all Parts of my Oratorio called the Messiah to the Foundling Hospital.”

In a score that is rich and magnificent, the work’s most recognizable section is its uplifting “Hallelujah Chorus,” which begins with exultant shouts of “Hallelujah!” Handel once remarked that while composing this part of the oratorio, he felt “as if I saw God on his throne, and all his angels around him.”

On first hearing the “Hallelujah Chorus” at the second performance of Messiah in London, King George II stood up, out of respect to the composer and the sacred subject. The audience, following his example, rose with him. Over the centuries and to this day, audiences continue to rise as the famous chorus begins, and remain standing until its conclusion.

Following Messiah’s first performance in London, one Lord Kinnoul complimented Handel on “the noble entertainment” that Messiah provided, and the composer is said to have replied, “My Lord, I should be sorry if I only entertained them; I wished to make them better.” The great classical composer Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) wept like a child in Westminster Abbey upon hearing the “Hallelujah Chorus” for the first time and said of Handel that “he is the master of us all.”

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©Matthew Hollow

The oratorio is divided into three parts. Part one foretells the coming and birth of a Messiah. It begins with the tenor soloist singing the opening phrase “Comfort ye, my people.” Here, Handel dictates in the musical score that trumpets sound “from a distance,” and they are first heard offstage before joining with the other musicians. The second part of the oratorio details the sufferings, death and resurrection of Christ, and it is in this section that the rousing “Hallelujah Chorus” is presented. The third part declares a faith in God and that the attainment of eternal life comes through belief in Him.

Messiah draws on Handel’s abilities as an operatic composer for its power; it is distinct from other works that came before it, and from most of Handel’s own oratorios, because of its rousing choruses and stately ceremonial music. Nothing like this epic work with its tremendous scope had been done before.

George Frideric Handel was born in Halle, a small German town, in 1685. His father was a barber-surgeon who wanted his son to be a lawyer. Handel’s talent for music was recognized early on, however, and he was eventually allowed to pursue that career. In 1702 he was appointed probationary organist at Halle Cathedral. At the end of that year, just when he was to be confirmed as the cathedral’s organist, Handel resigned and moved to Hamburg, the operatic center of Germany.

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_img3" align="alignright" width="1024"]

©Matthew Hollow

Handel began his lifelong love of opera by composing Almira in 1705, with other operas to follow over the years. In 1706 Handel left Hamburg for Italy, where he mastered a number of musical genres including opera and the oratorio. He returned to Germany as court conductor in Hanover in 1710, but soon left for London to compose for a new London theater company presenting Italian operas in Haymarket.

The budding composer relocated to London permanently in 1712 and received a royal pension from Queen Anne of £200 per year. While working in the medium of opera he adored, Handel also earned income as a court musician and composed ceremonial music for state occasions at St. Paul’s Cathedral and other churches in London. He continued to write music for royal occasions under the reigns of King George I and King George II. Even with all his commissions, money was usually scarce, and Handel often had financial worries like so many others in the arts through the centuries.

In the summer of 1723, Handel moved into a new house at 25 Brook St., which would be his home for the next 36 years, until his death. Handel became a naturalized English citizen in 1727. This was also the year that he composed Zadok the Priest for the royal coronation of King George II. The work has been sung in Westminster Abbey at every British coronation of a monarch since that time.

In 1738 a full-length marble statue of Handel was created by the French sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac and erected at the public gardens in Vauxhall on the south bank of the Thames. An unusual honor for a living composer, it indicates the high esteem in which Handel was held.

The Brook Street house is maintained today as a museum known as Handel House and is the only such structure in London devoted to a composer. Entered via a quiet, quaint cobblestone passage called Lancashire Court, around the back of busy Brook Street, the 18th-century house has been restored as Handel’s residence. There is an excellent video about his life continuously playing in what was Handel’s dressing room, and several rooms have been decorated to resemble what they would have looked like when the composer lived there.

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© MATTHEW HOLLOW

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

DANA HUNTLEY

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_img6" align="aligncenter" width="983"]

DANA HUNTLEY

The Composition Room, where Handel wrote his music, is impressive because of its small size—in contrast to the greatness of the compositions that poured out of it.

The Rehearsal and Performance Room, the largest space in the house, was where Handel often rehearsed many of his works and had friends and colleagues in to hear them performed. Today musicians often use the space with its beautifully constructed harpsichord, made several years ago to replicate what Handel would have played, to practice and rehearse. Regular concerts are also given throughout the year on Thursday evenings and Sunday afternoons. Handel House comes alive when there are musicians playing there, and it is well worth a visit.

Some of Handel’s other well-known works include his orchestral suites Water Music and Music for the Royal Fireworks. There has been renewed interest in recent years in Handel’s operas, and often seasons at the English National Opera and the New York City Opera will include one of these works in their repertoire.

While Handel wrote more than 40 operas and some 18 oratorios, along with various cantatas and serenatas, chamber music and other musical compositions, he is largely identified as the composer of Messiah.

Every year since 1742, Messiah has been performed somewhere. A note in the engagement diary of a George Harris in 1749 noted that he “heard Messiah rehearsed, Handel’s.” After 1750 and the first of the charity performances at the Foundling Hospital, the popularity of Messiah became and remains unprecedented.

George Frideric Handel, gave his last performance of Messiah on April 6, 1759, at Covent Garden. Returning home from conducting, he took to his bed. His health had not been good for several years, and he had also lost his eyesight. Eight days later, on the Saturday morning of Holy Week, Handel died. He had never married. By then, Handel was famous throughout the country; his works were performed everywhere and his name drew large audiences.

In accordance with his final wishes, Handel’s funeral and burial were at Westminster Abbey, where some 3,000 people gathered to pay their respects on April 20—further confirmation of Handel’s status as an English national treasure. A monument created by Louis-François Roubiliac, who had made the earlier Handel statue for Vauxhall Gardens, was later placed on the wall above Handel’s grave at Westminster Abby and remains there today. A fitting tribute, the monument’s life-size figure of Handel depicts him holding the musical score for his famous and ever popular soprano solo “I know that my Redeemer liveth,” from Messiah.

[caption id="HandelandhisMessiah_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

©LEBRECHT MUSIC AND ARTS PHOTO LIBRARY/ALAMY

Comments