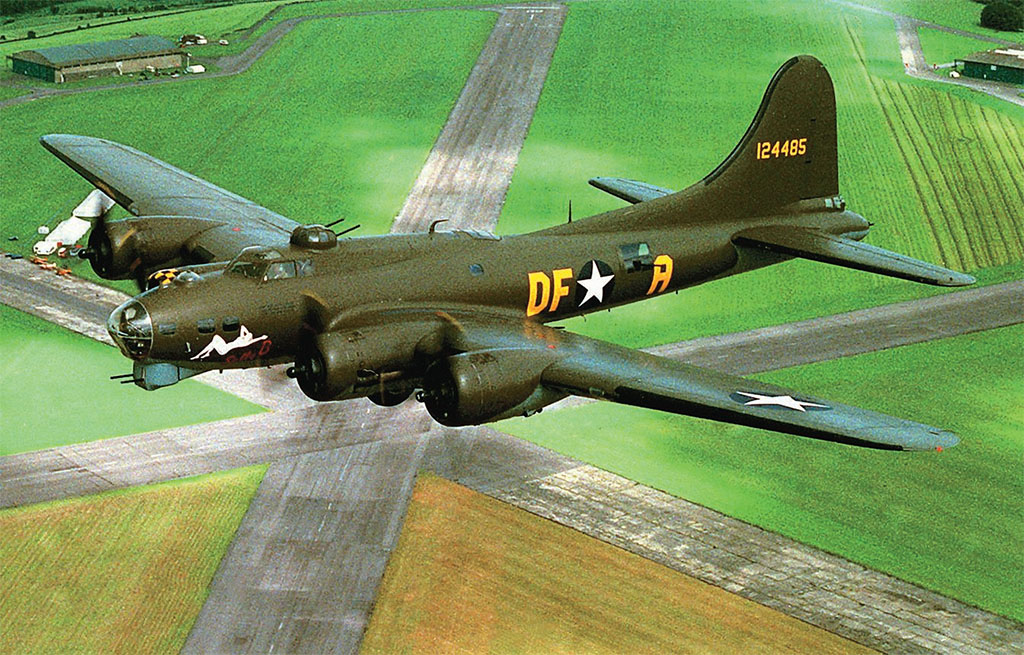

MY DAD, A WORLD WAR II VET, wanted to see the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. We were visiting the Imperial War Museum’s Duxford Aerodrome near Cambridge, which, as it turns out, has two B-17s on its campus. Up close, the B-17 is a very scary long-range bomber, huge and bristling with machine guns—all 13 of them, spread between seven turrets. Boeing designed the aircraft in 1935 to take 5,000 pounds of bombs hundreds of miles beyond the range of a fighter escort and still manage to get its crew back alive. Alas, the machine guns were not enough to stop waves of cannon-armed German fighters; early losses reached 25 percent before the North American P-51 Mustang fighter finally provided effective cover. Dad trained as a tail gunner in a B-17, just before the war ended. I tried to imagine his view from the tail turret, facing backward within a glass enclosure at the rear of the plane. Like I said, scary.

Good museums give good perspectives—and Duxford’s American Air Museum is very good indeed. Looking up from the B-17, we received another type of perspective; its mammoth grandchild, the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, loomed above us, almost as if it was folding its predecessor under its wing. Built just 20 years after the first B-17, this monster bomber will still be in service (according to the U.S. Air Force) when it is 100 years old, and its “newest” airframes more than 90.

Duxford Aerodrome has long been associated with American fliers. Founded in 1917, it trained American and British fliers during World War I and then served as a major Battle of Britain fighter base in 1940. In 1943 the Americans took it over, and for two years the U.S. Eighth Air Force used it to furnish fighter cover for long-range bombers.

In 1977 London’s Imperial War Museum purchased the derelict air base as a place to store and preserve its aircraft collection, while the Cambridgeshire County Council restored the runway and air control tower as a civilian airport. The collection immediately caught the interest of many American veterans who had flown from that area. Since then, Duxford’s historic aerodrome has become one of Europe’s most important aircraft museums—a place where historic aircraft are flown as well as displayed.

[caption id="HandsAcrosstheSea_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

PA/EMPICS

The Imperial War Museum has returned the air base to its World War II appearance, placing exhibits and aircraft restorations (open to the public) in the hangars. The major museums flank the old air base: The American Air Museum shares the far end with the British Land Warfare Hall, while the newly opened AirSpace Museum occupies the near end. AirSpace is a giant hangar-like structure that houses 30 of the finest British aircraft in the collection. Unfortunately, AirSpace was under construction and not completed when we visited, and many of its larger aircraft sat along the side, waiting to be moved in.

We walked past those planes as we went to the American Air Museum. First was the Concorde; last was the de Havilland DH-106 Comet. Both aircraft are famous—notorious actually—milestones in British civilian aviation. The Concorde on display there is number 101, built as a test aircraft and with its bank of test equipment still intact. It was flown into Duxford in 1977 but will never fly again; since then, motorway construction has cut off the end of the runway. The plane’s interior is open to the public.

The 1952 de Havilland Comet is noteworthy because it was the first commercial jet ever built. It was a big success—until its square windows caused enough accumulated metal fatigue to crash two jets. On display is the 1958 Comet 4, the safe version meant to replace the disastrous Comet 1—unsuccessfully, as the public had long memories.

At the far end of the historic base, the American Air Museum grows out of the earth like a giant, shining metal hangar, its curved south front a sheet of glass, its north end sunk into the ground. Inside are 20 aircraft, some hung from the single-arch ceiling, others parked on the floor; the glass wall can be removed to let the airplanes in and out. Wide, shallow-ramped mezzanines curve up each wall, allowing a view over the floor from all sides. As with virtually every modern building in England, this 1997 structure has no air conditioning, despite its half-acre of south-facing glass. On our warm spring day, the interior had gone beyond tropical, so our desire to linger was tempered by our need to find a shade tree and a cool drink. We held out for about an hour, but a normally cool English day would have kept us inside a lot longer.

As you might expect, the B-52D Stratofortress occupied the entire floor of the American Air Museum, the other planes fitted into the empty spaces surrounding it. Usually you can go right up to the bomber, and even inside; on the day we were there, unfortunately, the plane was closed off, surrounded by tall, spindly cherry pickers from which the staff cleaned a Lockheed U-2 spy plane hanging high above.

While my dad hunted for more World War II planes, I (a child of the Cold War) circled around on the mezzanine to view the amazing Lockheed SR-71A Blackbird, 40 years old and still looking like something from a science fiction magazine cover. Afterward, we headed for the Land Warfare Hall, where the Imperial War Museum displays its collection of tanks, artillery and vehicles in period settings, within a hall whose lighting fades to blackness along its outer walls.

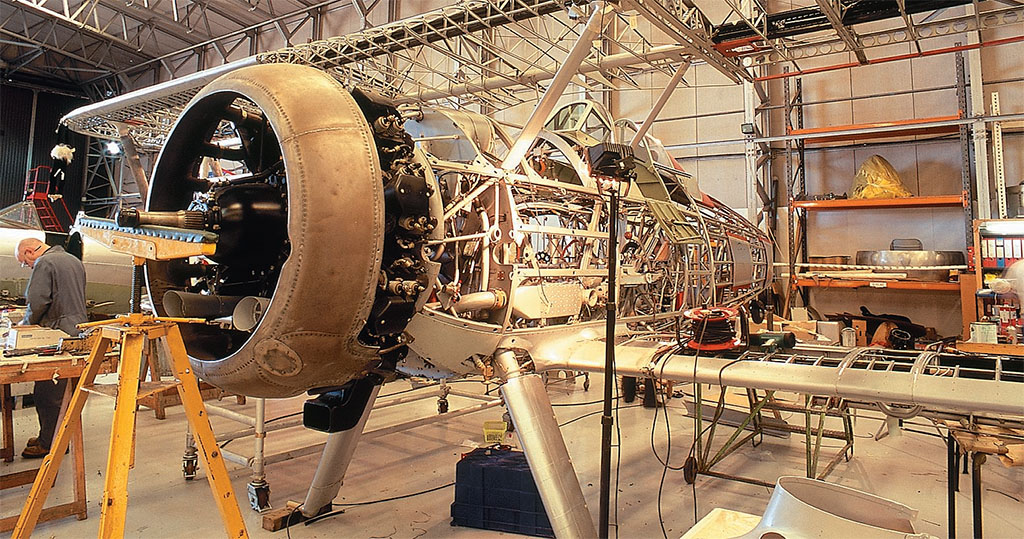

We eventually worked our way back through the hangars, favoring those with active restoration works. There we received one final piece of perspective from an allaluminum biplane, the Gloster Gladiator, a strange design throwback to the World War I era created to appeal to the hyperconservatives at the British War Ministry. That unlikely warrior (768 were built and used by Britain and nine other belligerents during World War II) was designed in 1935—the same year as the B-17.

[caption id="HandsAcrosstheSea_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="HandsAcrosstheSea_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="HandsAcrosstheSea_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

Comments