“IT WAS THE BEST OF TIMES, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity…we had everything before us, we had nothing before us….” So begins the Charles Dickens classic A Tale of Two Cities, my favorite work by the author who has been called “inimitable.” He was a master at crafting in-depth characters who became so popular that they remain familiar today, including Nicholas Nickleby, Oliver Twist, Little Nell, David Copperfield, Pip, Ebenezer Scrooge and Tiny Tim. More than a century after his death, Dickens’ novels continue to be read by contemporary audiences. What Christmas is complete without seeing a televised, animated or theatrical version of “A Christmas Carol”?

The Dickens Fellowship, based in London, provides a connection for Dickens enthusiasts through a worldwide association. Although it exists to commemorate the life and works of Charles Dickens, it isn’t just a reading club, and the members of the Fellowship do not limit themselves to purely intellectual pursuits. Since its founding in 1902, the Fellowship has campaigned against some of the social ills that most concerned Dickens and that appear in his works. The Fellowship also seeks to preserve and purchase buildings and artifacts associated with the author or mentioned in his novels, including the house at 48 Doughty St., where Dickens lived from 1837-39. The house now operates as the Charles Dickens Museum and serves as the headquarters of the Fellowship. Preservation and development work at the house continue to be a primary concern of the Fellowship, as well as at Gad’s Hill Place in Kent, the author’s last home.

In London the Dickens Fellowship’s calendar of events lists something for every month of the year, including talks, readings and socials. But the highlights of every year are a dinner celebrating the author’s birth on February 7 and a wreath-laying ceremony on the anniversary of his death on June 9, held at Westminster Abbey, where Dickens was interred in Poet’s Corner, against his wishes. The author had wanted a small private affair in a little cemetery in Rochester, but his readers wouldn’t have it. Other events include a commemoration service held at the church in Little Dorrit, St. George the Martyr in Southwark, and a Yuletide supper.

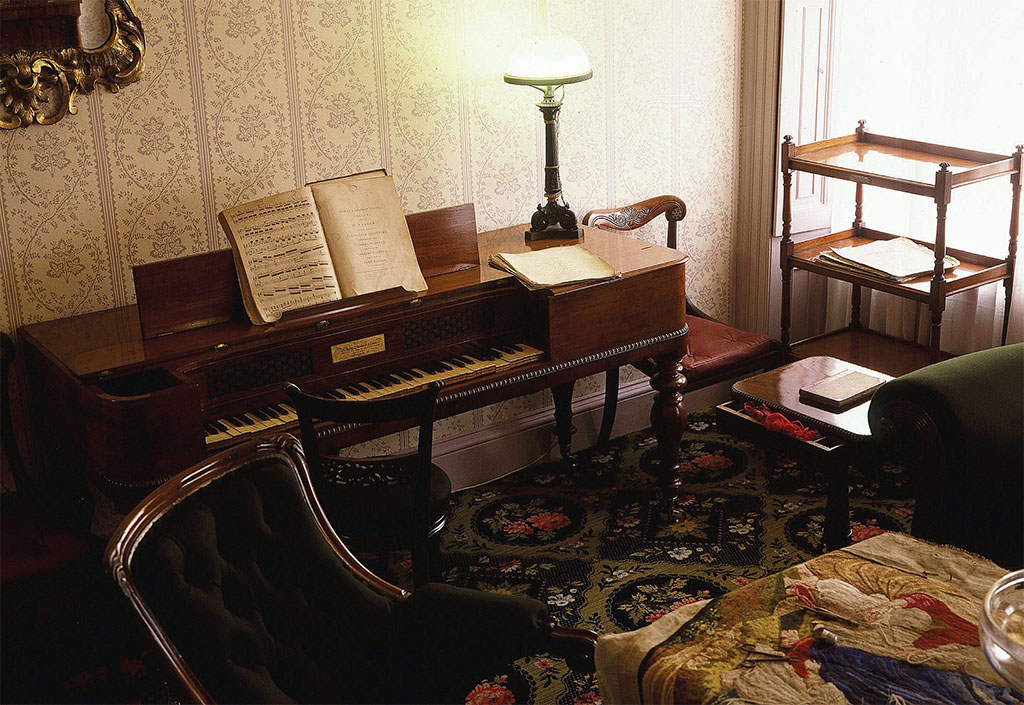

[caption id="HandsAcrosstheSea_img2" align="alignright" width="1024"]

DANA HUNTLEY

The 47 branches of the Dickens Fellowship—in the United Kingdom, the United States and nine other countries—take turns sponsoring an annual conference that addresses the business of the association but leaves plenty of time for lectures, entertainment and outings. This year, the Philadelphia branch will host the event from July 19 to 24. Established in 1907, the Philadelphia branch, along with that in Chicago, is among the oldest active branches in existence. The Chicago branch, established the same year, hosts a number of activities that include book, panel and dinner discussions, film and video presentations, theater parties, area tours and guest speakers. “True to the spirit of Charles Dickens,” the organizers promise, “we do all these in a spirit of fellowship and conviviality.”

In the United Kingdom, branches of the Dickens Fellowship are in Bristol, Clifton and Northeast England, while other U.S. branches include those in Pittsburgh, Pa., Palo Alto, Calif., and New York; each features a Web site with information about its activities and a welcome to prospective members. Links to the different branches appear on the Fellowship’s London Web site at www.dickensfellowship.org.

Fellowship members and nonmembers may subscribe to The Dickensian, a 96-page journal published three times a year. Under the leadership of editor Professor Malcolm Andrews of the University of Kent, each issue features articles on the life of Charles Dickens and his works, and reviews of books, theater presentations and television programs, as well as reporting on fellowship activities.

[caption id="HandsAcrosstheSea_img3" align="alignright" width="994"]

THE CHARLES DICKENS MUSEUM

Born on February 7, 1812, Charles Dickens was the son of John and Elizabeth Dickens and the second of eight children. John Dickens was a Naval Pay Office clerk until 1824, when he went to Marshalsea Prison for debt. While the rest of the family went to live with John in prison, the 12-year-old Charles was sent to work at Warren’s Blacking Factory. Though the experience was brief, it made a lasting impression, and many of the hardships he endured and observed as a child laborer would later appear in his writing.

THE ART ARCHIVE/DAGLI ORTI

After his father’s release from prison, Charles attended a day school in London from 1825 until 1827. He later found work as an office boy in a law office, a parliamentary reporter and then a newspaper reporter. Dickens enjoyed his first literary success in 1836, when monthly installments of The Pickwick Papers began appearing and became immensely popular. As a result he devoted himself to the full-time pursuit of writing.

Thereafter, he turned out an impressive number of complex storylines that eventually became 14 novels and numerous articles and short stories before his death in 1870. His best-known titles include Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, David Copperfield, Bleak House, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, Our Mutual Friend and of course “A Christmas Carol.” Dickens also traveled abroad extensively on reading and speaking tours and acted in amateur theatrical productions. His acting apparently was quite good.

It seems that his genius, however, wasn’t an easy gift for him or for those closest to him. In a letter to his wife Catherine on December 5, 1853, Dickens wrote, “The intense pursuit of any idea that takes complete possession of me is one of the qualities that makes me different—sometimes for good; sometimes I dare say for evil—from other men.” And in a letter to a friend dated April 3, 1858, Dickens confessed, “I hold my inventive capacity on the stern condition that it must master my whole life, often have complete possession of me, make its own demands upon me, and sometimes for months together put everything else away from me.”

Dickens wrote and toured feverishly. In worsening health after suffering a mild stroke in 1869, he continued work on his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. After spending most of June 8, 1870, writing, Dickens suffered another stroke and died the following day. To the last, his muse ruled him. But he wouldn’t have had it any other way. And for that, his readers are grateful.

Comments