THERE IS NOTHING QUITE LIKE the Folger Shakespeare Library anywhere in the world. The art deco granite edifice blends well into its surroundings on Washington, D.C.’s Capitol Hill. Apart from the bas-relief scenes from Shakespeare’s plays adorning its white marble facade, the library could be just another executive or legislative office building—or part of the neighboring Library of Congress. Within the building, however, architect Paul Cret has created an Elizabethan space. Visitor, reader, staffer or theatergoer: All who enter the portals of the Folger are taken back to the Renaissance world of the 16th century. Dark oak wainscoting lines gray stone walls, Tudor arches lead from gallery to hallway and the Tudor-rose motif adorns plasterwork ceilings.

Completed in 1932, the Folger Shakespeare Library was the fulfillment of a shared dream of Emily and Henry Folger. Rising in the business world to become president and then chairman of Standard Oil of New York, Henry Folger had the resources with which to indulge the passion he and Emily felt together for the great Bard of Avon. For more than 40 years, the Folgers engaged their mutual avocation—collecting tens of thousands of books, playbills, manuscripts, paintings and sundry objets d’art related to the incomparable William Shakespeare, his works and his times. In his retirement, Henry Folger devoted himself to the 10-year task of planning, designing and constructing this library to house the Folgers’ collection and to provide a world-class center for the study of Shakespeare and his age.

Perhaps no physical institution merits so well inclusion in our series on organizations that keep alive the vital cultural connection between Britain and the States. Apart from the collective authorship of the Bible, no writer has contributed as much to our shared language, or influenced our literature and our broader culture so extensively as the Elizabethan dramatist and poet. I was delighted to sit down with Folger Director Gail Kern Paster in her suitably Elizabethan withdrawing room to chat about the Folger’s history and its work today.

The Folger’s colorful and exuberant brochures often call the library “a lively place for learning and the arts.” Paster uses another phrase—“treasure chest and beehive”—to describe the library and its extensive programming. “We are a treasure chest because, after the British Library and the Bodleian, the Folger has the third largest collection of early books printed between 1470 and 1640,” she said.

[caption id="HandsAcrosstheSea_img2" align="aligncenter" width="689"]

Folger Shakespeare Library

That treasure chest includes 79 copies of the First Folio of Shakespeare acquired by Henry and Emily Folger, certainly the largest assemblage in the world. Head of Reference Georgianna Ziegler gave me a tour of the Folger treasure chest—what are literally vaults within the bowels of Capitol Hill. The First Folios are shelved on the back wall, each lying on its side, protected by carefully controlled temperature and humidity. Dust-free rows of shelving house an invaluable collection of early Shakespeare quartos and editions, and shelf upon shelf of important books printed in the 17th century and before.

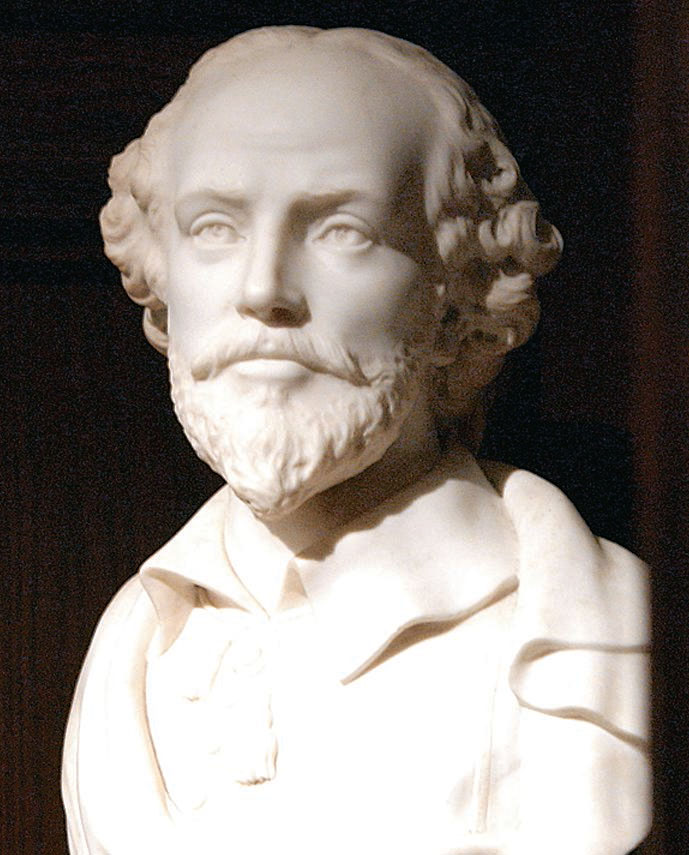

In a custom-made box crafted in the library’s conservation lab lies Queen Elizabeth I’s own pulpit Bible—the velvet-covered Bishop’s Bible presented to the queen by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Tucked amid a rank of cracked leather-bound tomes is John Smith’s first account of Virginia’s Jamestown settlement. Along the wall stretches the mounted 7-foot-long 1625 engraving known as Visscher’s View of London. Separate vaults house the Folger’s extraordinary collection of Shakespeare-related art: porcelain figurines, lithographs, sculpture and all manner of Shakespeare memorabilia going back to the 18th century.

As for the beehive reference Paster made, “This place is buzzing all day and night,” she enthuses. “We have so many different kinds of activities going on.” Indeed.

Plays, exhibitions, readings, concerts, educational programs and scholarly conferences go on throughout the year. Behind the scenes, the library maintains an ongoing program of publications and conservation projects. A full-time staff of 94 directs the work of the Folger.

Award-winning productions of the plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries are produced in the Folger Theatre. The intimate 275-seat theater, with carved-oak columns and three-tiered wooden galleries, resembles the kind of courtyard where traveling players might have performed in the 16th century. The Folger Consort presents music of the Middle Ages and Renaissance in an annual concert series. Nationally renowned authors speak and read in the Pen/Faulkner fiction series and Folger poetry presentations.

The Folger’s Exhibition Hall mounts two or three exhibitions a year, drawn principally from the library’s own collections. Presided over by the coat of arms of Elizabeth I, the vaulted plasterwork ceiling, dark oak paneling and long, narrow dimensions recall the long gallery of many an ancient English stately home. Upcoming exhibitions include “Shakespeare for Children” and “Shakespeare in America.” The adjacent Museum Shop proffers a variety of predictable goods—from Folger Library editions of Shakespeare’s plays to Shakespeare bobble-heads. Apparently anything inscribed with the line “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers,” from II Henry VI, iv, ii, is a bestseller.

At its heart, however, the Folger remains a serious academic library. The Old Reading Room is not open to the public. Shakespearean scholars, editors, professors and graduate students from around the world come to avail themselves of the unique resources at the Folger. Resident scholars, called “readers,” come for anywhere from one to nine months. Apart from its rare and antiquarian books, the library catalogs some 300,000 volumes related to Shakespeare and his times, available to readers in open stacks. Designed like the great hall of an Elizabethan stately house, and suitably lined with 16th-century French and Flemish tapestries, the Old Reading Room makes an evocative place to study.

For Paster, the Folger is a labor of love not lost. “It is such a privilege to be a part of this and to conserve these extraordinary resources for generations to come,” she said. A noted Shakespearean scholar and professor in her own right, Paster has been associated with the library for many years and became its director in 2002. In addition to serving as chief administrator of the Folger, Paster also edits the library’s journal of Shakespeare studies, Shakespeare Quarterly. “I am still teaching,” she admits, “but I miss the theater of the classroom.” Spoken like a true Shakespearean.

While not many of us will ever have the opportunity to find ourselves under the massive arches of the Old Reading Room, we are all richer for the enormous contributions the Folger Shakespeare Library continues to make to our understanding of and appreciation for the work of the immortal Bard and the Renaissance age he created. Web site: www.folger.edu

Comments