The Empress of Ireland ocean liner.Getty Images

The Empress of Ireland, also known as “Canada’s Titanic,” sunk while on a journey from Quebec to Liverpool - yet the story is not nearly as well known as it should be

On May 29, 1914, The Empress of Ireland sank, but its story has been largely forgotten. We look back at how the ship sank, its passenger lists, and the effect that this, "Canada's Titanic" had on the growing country.

The Empress of Ireland tragically sank on May 29, 1914. In this horrific maritime disaster, over a thousand passengers en route from Quebec to Liverpool were lost in just fifteen minutes—the length of time it took for the ocean liner to sink into Canada’s Saint Lawrence River after being hit by a ship called The Storstad. Canada was a growing nation of only eight million at the time, making the loss of over a thousand people in the accident a national tragedy.

Read more: A typewriter has been found on the 104-year-old Lusitania wreck

The Empress of Ireland, sister ship of The Empress of Britain, played a massive role in Canada’s flourishing population and economy in the early 1900s. She carried tens of thousands of passengers between Canada and Great Britain over a few short years and brought 100,000 newcomers to live in Canada. A licensed Royal Mail Ship (RMS), she transported a huge volume of mail between Canada and Great Britain as well.

The Canadian Museum of History unveiled a powerful, inclusive, detailed exhibition titled “Canada’s Titanic – The Empress of Ireland” for the 100th anniversary on May 29, 2014, which ran through April 6, 2015. It featured more than 500 recovered items from the wreckage, compiled by collector and diver Philippe Beaudry: documents and artifacts such as dishware and furniture from the ship’s separate classes, photographs, personal papers, the ship’s bell and porthole and an eight-year-old survivor’s memoir.

Artifacts salvaged from The Empress of Ireland disaster.

Read more: British maritime history

Overshadowed by the breakout of World War I two months later, the tragedy of The Empress was almost swept under the rug. President and CEO of The Canadian Museum of History Mark O’Neill said in a press release, “The poignant stories of its passengers represent a dramatic moment in Canadian history, one worth preserving for future generations.” He wants to make sure that the historical tragedy isn’t forgotten about simply because it was never given a Hollywood movie title a la Titanic.

Shelly Glover, the Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages, similarly expressed that as they approach their 150th anniversary of Confederation in 2017, she wants Canadians to “have more opportunities to learn about and experience their history.”

At 1:38 a.m. on May 29, 1914, the lookout on the crow’s nest of The Empress of Ireland spotted the mast of the headlight of The Storstad, which had been carrying 10,000 tons of coal. The two vessels continued to steam toward one another, and just nine minutes later at 1:47 the fog became too thick, hiding the ships from one another. There was a misunderstanding between the two captains about their respective boats’ positioning and direction, leading to the fatal collision. The Storstad hit The Empress of Ireland broadside, tearing a 350 square foot hole in her hull.

With water pouring in at 60 gallons per second, the ship sank rapidly. Hundreds of sleeping passengers were trapped, and the second and third class passengers had much less of a chance at survival than the first class passengers, as first class was higher up on the boat. Out of 1,477 passengers, only 465 survived. And out of 138 children that were on board, only four survived.

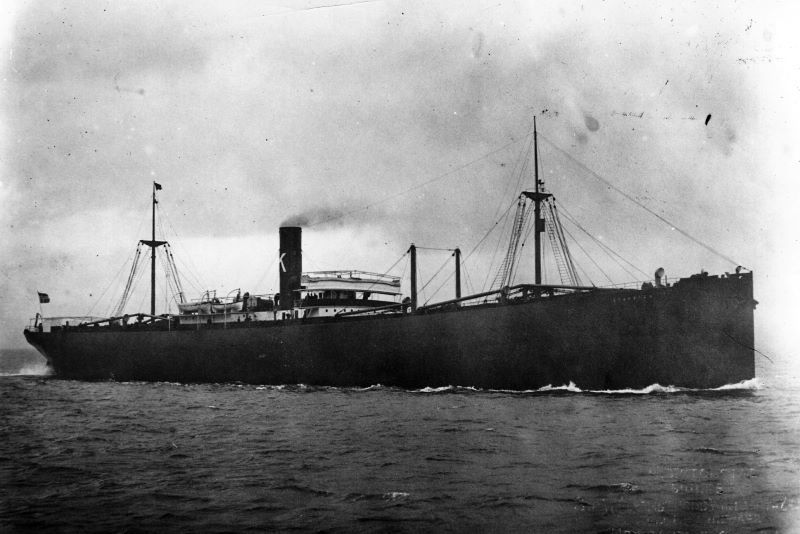

The Storstad, circa 1910 (Getty Images)

Crewmembers of The Storstad (which was left unharmed) along with two other rescue ships from the nearby city of Rimouski came to pick up the survivors. The survivors were then taken to Rimouski where they were taken care of. As for The Storstad, it continued on its journey to Montreal with just a broken bow.

Among the passengers were many Irish. Grace Hanagan, of Irish descent, was the youngest and last survivor of the tragedy. She passed away in 1995 but spent the rest of her life spreading her story and keeping in contact with other survivors.

Much of third class was made up of laid-off Detroit Ford workers returning home to Europe, along with many attempted immigrants who weren’t able to make it through.

Crew members of the Empress of Titanic, pictured the same month of its sinking (Getty Images)

Read More: The last letter written on board the doomed Titanic

Today, The Empress of Ireland is accessible to divers, at only 130 feet below the surface. It has been visited by those experienced enough to dive in such cold temperatures hundreds of times since the ship’s rediscovery in the mid-1980s. However, it’s been buoyed off as “historical and archaeological property,” and divers must follow a strict set of rules to ensure they don’t damage the site.

Only a couple of weeks after the disaster, Canadian Pacific hired a salvage company to dive down, blast a highway into the heart of the ship and fetch the mail from the first class cabin. They also retrieved what would be two million dollars today.

Divers have encountered all sorts of decaying debris like shattered suitcases, china, chairs and tables, light fixtures and the like—Philippe Beaudry was dedicated enough to create an extensive collection of his findings with over 500 objects, and he also contacted and traded with other divers in order to further build it.

One diver entered the mailroom and discovered a box of neatly bundled and tied newspapers with paper still white and print still readable, dated May 27, 1914, but when he returned for it, the silt at the bottom of the river had shifted and buried the papers. Unfortunately divers have taken most of the human bones as well.

Salvaged letters from The Empress of Ireland.

* Originally published on IrishCentral in May 2014 for the centenary of the disaster.

Comments