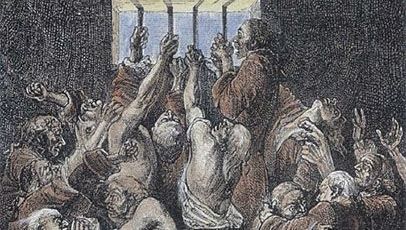

An artist’s conception of conditions inside the “Black Hole,” based on Holwell’s account.THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NEW YORK

Just how "black" was the Indian prison, Black Hole of Calcutta? A genuine narrative of the deplorable deaths of the gentlemen who were suffocated in the Indian prison known as the Black Hole of Calcutta.

Editor's note: On June 20, 1756, in India, over 140 British subjects were imprisoned in a cell measuring only 5.4m by 4.2m, named The Black Hole of Calcutta, only 23 came out alive.

"Then was committed that great crime, memorable for its singular atrocity, memorable for the tremendous retribution by which it was followed. The English captives were left to the mercy of the guards, and the guards determined to secure them for the night in the prison of the garrison, a chamber known by the fearful name of the Black Hole."

—Thomas Babington Macaulay.

140 "Figure to yourself, my friend, if possible, the situation of a hundred and forty-six wretches … crammed together in a cube of about 18 feet, in a close sultry night, in Bengal, shut up to the eastward and the southward by dead walls, and by a wall and door to the north, open only to the westward by two windows strongly barred with iron, from which we could receive scarce any the least circulation of fresh air..."

—John Zephaniah Holwell.

In the case of historical events about which we have only one firsthand account, that account often tells us more about the eyewitness’ prejudices than about historical truth. At other times, it’s nearly impossible to separate fact from fiction with any certainty. One of history’s greatest infamies falls into this category.

The first-hand account belongs to John Zephaniah Holwell, an Irish doctor who went to India in the service of the East India Company and subsequently survived a night in the prison known as the Black Hole of Calcutta. The East India Company, ostensibly a trade conglomerate, operated largely in proxy for the British Government, overseeing Britain’s investment in India even to the extent of maintaining its own army. In 1756 the new Mogul Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-daulah, decided that the East India Company was a threat to his power and demanded that the British dismantle the fortifications at Fort William. When they refused, he attacked.

In the long run, of course, the Nawab’s army was no match for the might of Britain, but the small garrison at Fort William was overwhelmed like a pebble in a flood. What happened next is open to question. According to Holwell the Nawab’s troops rounded up 146 British soldiers and herded them at the point of bayonets into the fort’s prison, a single cell designed to hold six people.

Descriptions of the “Black Hole” vary considerably. Holwell’s first-hand account established its dimensions at 24 by 18 feet. Other descriptions made the cell out to be 20 by 20 feet, or maybe 18 ½ by 14. Holwell described two barred windows; others said there was only one, or that there was no window at all. The one statistic all seemed to agree upon was the number of British soldiers incarcerated, 146, a figure that is almost certainly; in error.

Without water or food, Holwell recounted, the prisoners endured a sweltering night in the Black Hole. When the Indian guards returned in the morning, only 23 of the captives remained alive. So tightly packed were the occupants of the room, Holwell said, that many of the dead were still standing upright because they had no room to fall.

At first, there seemed no reason to doubt Holwell’s story. Of the 22 other survivors of the ordeal, none openly contradicted his version of the events, and a number vouched for it. Skeptics, however, note that Holwell’s version of events served him well, making him into something of a celebrity, if not a hero. In the wake of his published account, he rose to become the British Governor of Bengal. Fair enough reason, it might be argued, for embellishing his tale in an effort to “make a good story better.”

For more than 150 years, the story of the Black Hole enjoyed widespread acceptance. Then, in 1915, researcher J.H. Little published an article that began to throw great doubt on the details of Halwell’s version. In fact, Little seems to have suspected that the incident might never have happened at all. While that judgment probably swings too far to the opposite extreme, it now seems pretty clear that Holwell took considerable license with the facts. For example, the records of the Fort William garrison indicate that even after the alleged atrocity, only 43 soldiers were unaccounted for—the maximum that could have been killed in the Black Hole. In fact, the total number captured by the Indian attackers numbered less than 70, or about half the number Holwell claimed had been in the cell with him.

Indian historians themselves did not go so far as to say that the Black Hole was a total myth, but their own research suggests that whatever cruelty was inflicted was most probably unintentional, resulting from dreadful disorganization and poor communication among the Nawab’s men that led to the prisoners being confined far longer than originally intended. Not that this would have been of any comfort to those in the cell, but it does take some of the sting out of charges of Indian barbarity.

Here is a short history podcast on the Black Hole of Calcutta:

* Originally published in July 2016, updated in 2024.

Comments