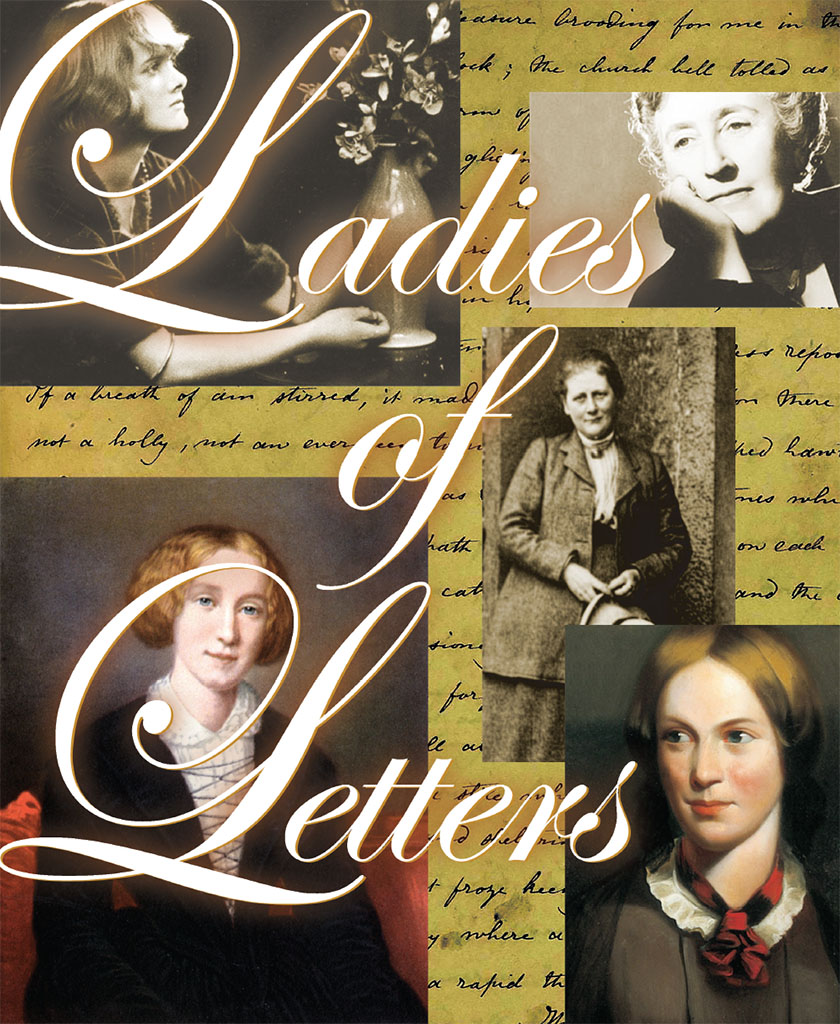

Where do writers find their inspiration? Is fiction an escape or a mirror to their lives?

Perennially intriguing, such questions perhaps prick all the more where some of England’s greatest women authors are concerned— hiding behind male pseudonyms and defying social propriety with their outpourings. Dreaming up best-selling children’s tales—and murder most foul.

Stepping into their homes, you can meet the personalities behind the pens and still walk out into scenes scarcely changed since these authors drew breath from them and gave them new life as literary landscapes.

While Sandra Lawrence trips along with Jane Austen (p. 44), here are visits with some of England’s other great ladies of letters in their real and fictional worlds.

[caption id="LadiesofLetters_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="840"]

WIKIMEDIA; WIKIMEADIA; © THE BRONTE SOCIETY

The Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth

You can easily imagine the stunned disbelief among genteel 19th-century readers when the brotherly pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell were stripped to reveal three sisters. Even more so when the authors of Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey proved to be the spinster daughters of a country parson. How could they write with such dark, raw emotion and realism?

Similar thoughts teem through the mind as you explore the Brontë Parsonage in the West Yorkshire hilltop village of Haworth, the sisters’ home from 1820, when their father, Patrick, became the local curate. Modestly furnished and kept spotlessly clean, surely this home typified the humdrum, sheltered world of young women of a certain time and background? But turmoil stirred below the neat surfaces and on the threshold.

The Brontë girls were still infants when their mother died in 1821; their two elder sisters expired within another four years; their brilliant but weak brother, Branwell, would become hooked on alcohol and opium. Allowed to roam with unusual freedom across the wild moorlands on their doorstep and through the literature of Byron and Scott, Charlotte, Emily and Anne escaped into their imaginations.

Suddenly you can picture them here: in their study creating their tiny handmade books; Anne baking bread and scribbling poems in the kitchen; all three penning their early novels in the dining room, discussing their work in a nightly ritual of walking around the table. Still tragedy stalked; they all died young, between the ages of 29 and 38.

This year is the bicentenary of Charlotte’s birth, and “Brontë 200” celebrations continue over the next four years with events to mark the bicentenaries of the births of Branwell, Emily and Anne, bridged in 2019 with a bicentenary commemoration of Patrick’s invitation to take up his post at Haworth Parsonage.

If you’re energetic, there’s also a 43-mile Brontë Way taking in landmarks that inspired the sisters.

Visiting: Brontë Parsonage Museum, Haworth, Brontë Country.

George Eliot’s Warwickshire

Mary Anne Evans (1819–1880) also felt obliged to publish under a masculine nom de plume, in order to have her writing taken seriously by Victorian society. She needn’t have fretted. Charles Dickens and Queen Victoria herself became fans of George Eliot’s groundbreaking psychological realism, and to this day Middle-march is acclaimed among the greatest English novels.

© THE BRONTE SOCIETY

Travel with Scenes of Clerical Life to the Arbury Estate on the outskirts of Nuneaton, where Mary Anne was born on a farm and her father worked as a land agent. Here you’ll find Arbury Hall (open to the public on selected days) that became her model for Cheverel Manor, the Gothic-style “castellated house of grey-tinted stone” in Mr. Gilfil’s Love Story. Mary Anne would accompany her father to the Hall when he had business here and wait in the housekeeper’s room or listen to servants’ tales; she was even permitted use of books in the library. It all fed her keen intelligence.

Also explore fact-into-fiction churches and Nuneaton (Milby in Scenes) including Eliot displays in the Museum & Art Gallery. For refreshment there’s always redbrick Griff House on the Coventry Road, where Mary Anne lived from the age of four months old. On the outside it evokes the Tullivers’ “trimly-kept, comfortable dwelling house” in The Mill on the Floss; inside it’s now a popular steak restaurant.

Visiting: Arbury Estate and The Griff House.

Beatrix Potter’s Lakeland

If you aren’t wandering after William Wordsworth’s golden daffodils in the Lake District, it’s creatures from Beatrix Potter’s “little books” that you expect to glimpse: Squirrel Nutkin paddling his twig boat on Derwent Water; hedgehog washerwoman Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle singing “Lilly-white and clean, oh!” against the majestic backdrop of the Newlands Valley; Mr. Jeremy Fisher, the frog afloat on a lily-pad on Esthwaite Water. This year, the 150th anniversary of Potter’s birth (1866), there’s even a “rediscovered” Tale of Kitty-in-Boots published in September adding to the cast.

WIKIMEDIA

London-born Potter was enchanted by childhood holidays in the Lake District, sketching flora and fauna with a scientist’s eye for detail. But it was romance rather than realism that made her name, beginning with the color publication of The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902). First conceived as an illustrated letter to a friend’s sickly son, this story alone has sold more than 45 million copies worldwide. Potter’s anthropomorphic visions of rural life have never gone out of fashion.

© NATIONAL TRUST/VAL CORBETT

Potter bought much land to protect it from development and on her death in 1943 bequeathed 4,000 acres and 15 farms, including Hill Top, to the National Trust. Thus she preserved two Lake District landscapes for posterity, the real and the imaginary.

Visiting: Hill Top and the Beatrix Potter Gallery, Tower Bank Arms.

Agatha Christie’s Riviera

We Brits can’t resist a cozy murder mystery to ruffle a sleepy old English village or peaceful library in a country house—with an eccentric sleuth to follow the clues to the dastardly perpetrator.

We’re not alone. “Queen of Crime” Dame Agatha Christie (1890–1976) wrote more than 80 novels and plays, selling some two billion copies worldwide. Her bumptious Belgian detective Hercule Poirot and deceptively sweet (but shrewd) elderly spinster Miss Marple remain perennial crime-fighting favorites of page and screen, while her Mousetrap whodunit is currently in its 64th year—the world’s longest-running show—at London’s St. Martin’s Theatre .

Christie, born Agatha Miller, was raised in seaside Torquay, and constantly returned to the genteel world of her native south Devon for the settings of novels. Mild in climate and culture, the “English Riviera” was ripe for murder most foul, and the Agatha Christie Literary Trail (available from visitor centers) guides you to places the author featured in more than 20 novels.

© NATIONAL TRUST/JOE CORNIS

Best of all, south of Torquay and overlooking the River Dart below Galmpton is Greenway: “the loveliest place in the world” that became Christie’s holiday home from 1938 and inspiration for Nasse House in Dead Man’s Folly. Full of family collectibles, including Agatha’s Steinway piano in the drawing room, it conjures up a vision of a gentlewoman perfectly comfortable with her life of crime—and even with the incongruous wartime frieze in the library; it’s Lt. Marshall Lee of the U.S. Coast Guard whodunit, stationed here in the run-up to the D-Day landings.

It’s a slightly tricky journey to get to Greenway (see website for directions), but well worth a visit and you can stay, too, in self-catering cottages.

Visiting: Agatha Christie’s Riviera, Greenway.

Daphne du Maurier’s Cornwall

The hired car swept round the curve of the hill and suddenly the full expanse of Fowey harbour was spread beneath us … like the gateway to another world. My spirits soared."

Thus Daphne du Maurier (1907–1989) recalled first glimpsing her new family holiday home in the 1920s, when she was just 19; thus Cornwall became her escape from London and the gateway to a rich fictional world that would give us the likes of Jamaica Inn (the eponymous real-life inspiration is on Bodmin Moor), Rebecca and Frenchman’s Creek. Cornwall’s mazy inlets, coast-hugging villages, smugglers’ haunts and taverns had captured her.

© NATIONAL TRUST/ANDREW BUTLER

One reader of du Maurier’s first novel was so enamoured that he sailed his yacht up the Fowey estuary to meet her. She married Tommy, later titled General Sir Frederick Browning, in 1932, and they honeymooned afloat, west along the coast amid the secretive reaches of the Helford river and Frenchman’s Creek, where in the novel of that name impulsive Lady Dona St. Columb found her pirate lover. Return to Fowey for a seafood supper with Cornish ale at the 16th-century Ship Inn, also featured in Frenchman’s Creek.

Visiting: www.fowey.co.uk

Comments