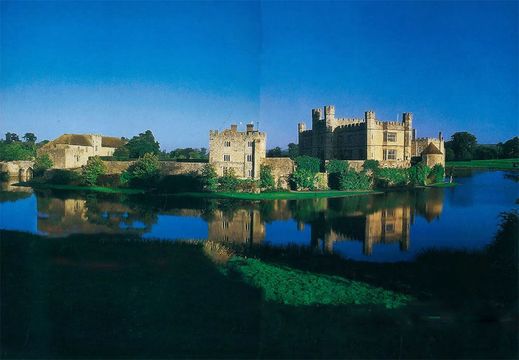

Seen from across the moat, Leeds Castle looks more suited to impressing visitors with its idyllic charm than to repelling invaders intent on destruction.

When Lady Baillie visited Leeds Castle she could see what Hearst could not it was one of the most beautiful places on earth.

When Leeds Castle came on the market in 1924, William Randolph Hearst was ready to buy it — that is. until he saw it. On paper, it seemed to be the perfect opulent party pad. Located just east of London’s Medway Valley, it was a real royal castle, eight centuries old, yet fully habitable and ready for renovation. We can only imagine Hearst’s disappointment when he saw it (and promptly nixed the deal). Where are the looming walls? The soaring battlements? The holes for pouring boiling oil on attacking soldiers? The dramatic keep, with a dungeon full of torture instruments? Sure, it had a moat (and a very good one), but…what happened to the rest of the castle?

Fortunately for the rest of us, Hearst gave it a pass, leaving it to a much more appreciative and tasteful buyer: wealthy socialite Olive Wilson Filmer, later known as Lady Baillie. The daughter of an English lord and an American oil heiress, Lady Baillie moved gracefully through the social elite that only old money and aristocratic ties could reach. When she visited Leeds Castle in 1926 she could see what Hearst could not—that Leeds Castle, with its 500 acres of parkland and 5,000 acres of surrounding farms, was one of the most beautiful places on earth.

A view, from just inside the Gatehouse, of the front facade of the main castle hall. Iim Hargan

Leeds enters history as a royal estate of the Saxon kings at least as early as AD 850. The Saxon monarchy didn’t go much for castles, but they did fortify their large stone mill on the River Len. In all likelihood, this mill sat on a sharp meander curve of the little river, with its outflow forming a cutoff on the narrow meander neck; this formed a backwater lake with two islands in the middle. And this is what you see today. The two islands are now wholly taken up by the castle, while the meandering lake forms the wide, lovely moat that surrounds it. As for that Saxon mill, its ruins still guard the stone bridge crossing over to the castle.

One of the great Norman noble families gained the estate from the king in 1119 and began constructing the modern castle. They used the fortified mill as an entrance defense. From there a drawbridge and gatehouse led to the large island, surrounded by curtain walls and functioning as the castle’s bailey, a large open area dedicated to domestic and garrison functions.

The small island, protected by wide stretches of water I reachable only by a bridge from the bailey, they converted into their keep—a tower where the noble family kept its private quarters and entertained its noble retainers. Much of Leeds’sophisticated beauty stems from this very practical arrangement, perfected by 1290.

In particular, the three-storey keep, now known as the "Gloriette,” adds much to the structure’s charm and grace. Most medieval keeps are tall, narrow, massive towers that stand isolated in the middle of the bailey as a final line of defence. In contrast, Leeds’keep is low, wide, and beautifully proportioned. It looks like a single structure, built of golden limestone in a D-shape, taking up the entire small island, linked to the main island by an enclosed bridge sitting on narrow arches. In fact it is a range, of structures surrounding a small inner courtyard, the fountain court. In medieval times this was the keep’s water supply, and is now an enchanting little space.

Leeds was always more of a fortified manor than a military structure, with its keep built for comfort and beauty rather than for withstanding sieges. And this is what made it so attractive to the kings of England—and, most especially, their queens. In 1278 King Edward I gained control of Leeds Castle and estate and promptly made it a country retreat for himself and his beloved queen, Eleanor of Castile. While Edward improved the moat and strengthened the defences (the 30-foot walls that rise from the water are his), Eleanor converted the castle keep into the luxurious Gloriette—a Moorish term she introduced from her native Spain. Edward survived Eleanor and remarried; Leeds then became the principal residence of his new queen, Margaret, remaining so throughout her widowhood. This became the traditional pattern for the English royal family for the next three centuries; the castle became the home of the queen, remaining so into her widowhood.

Leeds’only serious military action resulted from this precedent. Edward II’s queen, Isabella, tried to enter Leeds Castle only to find it in possession of one Lord Badlesmere, to whom the King had given it without bothering to inform Isabella. Words were exchanged and tempers rose; Badlesmere’s archers fired on the Queen’s party, killing several of its members. Legal grant or no, the enraged King besieged the castle, quickly took it over, and beheaded Badlesmere. Queen Isabella regained the castle and held it till her death.

Leeds Castle continued as the home of the queens of England until the reign of Henry VIII. Henry lavishly rebuilt Leeds as a grand palace for his first queen, Catherine of Aragon. However, when that marriage turned ill, Henry retained possession of Leeds and used it as a stopover point on his many trips between London and the Continent. When Henry’s young son Edward VI ascended the throne, Edward’s Protectors gave it away to one of Henry’s ministers. Leeds left the possession of the queens of England forever.

Of all the medieval queens to call Leeds home, the castle’s modern curators have singled out one special woman to profile—Queen Catherine de Valois, who took possession of the castle in 1422. There are good and practical reasons for this; the curators possess original records detailing the uses of the Gloriette’s rooms and their contents from 1414 and 1422, and this certainly makes a reconstruction easier. However, Catherine is interesting and important enough in her own right. At the time of her husband’s death she was just 21, a beautiful French princess in a strange land. She had a scandalous affair with an obscure young Welshman named Henry Tudor, landing them both in gaol for a time. Later they married and their grandson, Henry VII founded the Tudor dynasty.

JOURNEY NOTES

Iim Hargan

Getting there: Leeds Castle is about an hour east of London, just off the M20 (the main London-Dover freeway), Exit 8. It’s 8 miles east of the busy market town of Maidstone and about half an hour west of the Chunnel. If you are staying in London, you can get a bus (called a coach in England) from National Express Coach (tel: 08705 808080; web: www.nationalexpress.co.uk) at Victoria Coach Station; the fare includes admission to the castle. National Express runs a similar service from Kent’s coastal towns of Dover, Hythe, and Folkestone. Train service also operates from London’s Victoria Station, with transportation to the castle, and castle admission included in the price; you can ticket the train service from just about any city or town in the south of England.

Admission and Open Days: £ 12.50 for adults, £11 for seniors and students, £9 for children ages 4-15, and free for younger children. Off-season rates (roughly November through February) are lower. It closes only on the days of the June, July, and November events below and on Christmas Day.

Events and Activities: Leeds Castle offers two open-air concerts in late June/early July, the internationally famous Great Balloon and Vintage Car Weekend in early September and a grand fireworks festival in the first week of November. Hot air balloon rides are available daily at sunrise and sunset, and there is a public golf course on the castle grounds.

Contact: Leeds Castle, Maidstone, Kent ME 17 I PL, UK; tel: 01622 765400; fax: 01622 735616; email: [email protected]; web: www.leeds-castle.com.

Queen Catherine’s rooms in the Gloriette are now carefully reconstructed to their 1422 appearance. The Queen’s sumptuous bedchamber has walls covered in damask embroidered with the monogram HC tied in a lover’s knot, symbolizing the hoped-for union of England and France in the marriage of Henry and Catherine. The monograms continue on the rich red bedcovers and draperies, and on a day-bed raised on a dais and topped by draperies shaped into a crown—an impressive place from which to receive visitors. Next door is luxury of a more practical kind—an accurate reconstruction of Queen Catherine’s bath, hung with white linen; it emptied through a valve in the floor.

Leeds remained a private residence from the time of the Tudors to the time of the Windsors. Some owners kept it up better than others. By the 1920s it was not in the best of shape. One of William Randolph Hearst’s agents put it eloquently, if not grammatically, “Needs expenditure large sum to make it habitable not a bath in place only lighting oil lamps servant quarters down dungeons.” One presumes that the $875,000 that Lady Baillie paid for it went as much for the 5,000 surrounding acres as this run-down old pile.

Lady Baillie spent the next 50 years whipping Leeds Castle into shape. She retained Paris’finest decorators of that era, Armand Albert Rateau and Stephanie Boudin, to reconstruct the interiors in a stunning 17th-century French style. On the larger island, the main castle structure had been reconstructed by Henry VIII, then re-reconstructed in the high Jacobean style, then (in 1822) re-re-reconstructed back to Henry VIII’s style—thus earning the title the “New Castle.” This became an area for guests and entertaining. The Gloriette, attached to the New Castle by an enclosed bridge, became a private sanctuary for Lady Baillie and her family. Her bedroom, carefully preserved and open to public view, retains its 1936 Regence decor by Boudin; its gilt-edged blue panelling was wire brushed, limed, glazed, and then finished with beeswax to give it that ancient look.

Not all of Lady Baillie’s decorating was French in style, and some of the Gloriette’s most impressively ancient-looking features date from the 1920s instead of the 1220s. In the Fountain Court, a lovely half-timbered wall looks so old you wonder why Henry VIII hadn’t replaced it—yet it was built new as part of Lady Baillie’s improvements, softening the tall stone walls that loom over the court. Just as old-looking is a circular staircase, lined with roughly carved oak panels, anchored by a single massive oak trunk topped by an enigmatic laughing crusader—another addition by Lady Baillie, designed by Rateau.

More than any of the queens of Leeds’ history, Lady Baillie’s influence suffuses the castle. One example: Lady Baillie adored birds. Porcelain birds, carved birds, bird prints, and bird paintings are found in nearly every room. In the 1950s she took a further step; she developed an aviary that today holds more than 100 species. Redesigned and expanded in 1988, Lady Baillie’s aviary now hosts a successful breeding programme aimed at reintroducing threatened species to their native environments.

Lady Baillie was more than a decorator or improver. She was an artist, and Leeds was her canvas. Surrounded by water and framed by lakes, the golden stone of Leeds Castle is merely the centrepiece of a gently gardened landscape. Glades of trees grow in harmonious combinations; flowers brighten edges, seemingly at random, throughout the season; ducks congregate in ponds, search the lawns for snails, and happily bother strolling visitors. But the single most impressive elements may well be the black swans. Imported by Lady Baillie from Australia, they thrive and prosper in the moat, lakes, and ponds; they glare grumpily at gawkers, then casually strut and pose as if to say, “I was going to do this anyway—I am definitely not showing off for you.”

LADY BAILLIE HAS LEFT LEEDS CASTLE FOR ALL OF US. Upon her death in 1974 she bequeathed her beloved castle to the Leeds Foundation to keep it preserved and accessible for all times. The Leeds Foundation has researched and restored the Catherine de Valois rooms, expanded the size and mission of the aviary, and continued the growth and maturity of the castle gardens. The Foundation has also made the castle a venue for the performing arts as well as a site for such festivals as an annual hot air balloon gathering and the largest fireworks display in south-east England. And it is the Leeds Foundation that has established a small, world-class conference centre (with 21 rooms) in the New Castle, that (among other accomplishments) has hosted the preliminary talks for the Camp David Accords. They have preserved intact the room where Cyrus Vance, Moshe Dayan, and Mohammed Ibrahim Kamel sat down together—the United States, Israel, and Egypt at the same table for the first time. Then and now, Lady Baillie and her daughters look down approvingly from their portrait on the wall.

* Originally published in 2016, updated in 2023.

Comments