Stars and stripes and the Union Jack: The US and UK's special relationship. Getty

British Heritage readers appreciate and understand the much-cited “special relationship” between the United States and Great Britain more than most good citizens of either federation.

After all, British Heritage plays a critical role in keeping that relationship alive.

As the voice of British travel, history, and contemporary culture, this magazine takes great pride in championing the unique kinship we share with Britain, her intellectual history, and her people.

From whence does this kinship come, and to what can it point our nations now?

History of the Union

Originally, of course, it began with our colonial history and the four Great Migrations that populated our Eastern seaboard in the 17th and early 18th centuries. That story and its impact on our cultural history are beautifully told in David Hackett Fischer’s Albion’s Seed.

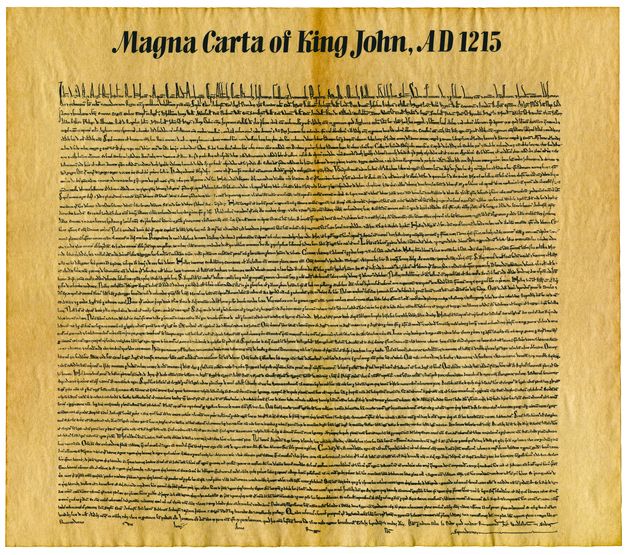

Our American charter documents were formed in English philosophy and jurisprudence from Magna Carta to John Locke. Representative democracy, trial by jury and separation of powers were forged in centuries of British political evolution.

To these concepts, we added the rights and respect for individuals that took intellectual force in the Reformation and the Enlightenment. Our modern democracies, though different in form, share these commitments today.

Within rapidly fading memory, our nations stood in an alliance of arms and spirit against common military and moral foes in the two World Wars of the 20th century. Since the last of those wars, Britain and America have remained each other’s closest international allies through the Cold War and the dangerous recent years.

Beyond our shared commitment to democratic government, human rights, and a strategic alliance, however, what binds our kinship is our language and the shared institutions our cultural history has created.

The Magna Carta

The bond of language

Language is the medium of communication that shapes our conception of the world. Nuanced, complex, adaptive, and confusing to foreign ears, the rich English language does create a bond between those whom Churchill described as “the English-speaking peoples.”

Generations of American youth grew up discovering that richness and that bond in Treasure Island, Great Expectations, Shakespeare and the King James Bible. We learned poetry with Wordsworth, Yeats, and Auden. If we were fortunate, we were introduced to Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy, and D.H. Lawrence.

While we might be two countries separated by a common language, as G.B. Shaw famously quipped, it is a common language. That itself has allowed us to freely share our literature, popular culture, ideas, and history. It has allowed the Beatles, Monty Python, Brideshead Revisited, and Agatha Christie to be a part of our culture, and Johnny Cash, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Madonna and Mark Twain to be part of Britain’s. There is so much that simply does not translate.

‘A common language has allowed the Beatles, Monty Python, Brideshead Revisited and Agatha Christie to be a part of our culture’

Language is only the base of the shared supra-culture of our Anglo-American alliance. Few of us go through life untouched by one or more institutions that have their origin in Britain. To varying degrees, we naturally feel common cause with these institutional roots.

Special interests

Then there are the countless special interests we pursue; so many of them, too, have an indelible and intrinsic British connection. Enthusiasts of Jane Austen, Jethro Tull, Shakespeare, Doctor Who, Gilbert & Sullivan, Charles Dickens, and the Stones will all agree. So, also, will members of British car clubs, St. Andrews’ Societies, medievalists, and serious gardeners all over the country.

At Christmastime, we send cards in the English tradition, sing English carols (as Siân Ellis details on page 35), decorate our mantelpieces with Victorian scenes, and watch A Christmas Carol.

Despite the dramatic regional differences in the landscape across our continent, somehow we seem to be instinctively drawn to the landscape of the British imagination. Both Harry Potter and The Chronicles of Narnia take place across such a landscape. It is Tolkien’s Shire, Hardy’s Wessex, Sherlock Holmes’ London, and the setting of Lorna Doone and Wuthering Heights.

Friction

Of course, in any kinship relationship, no matter how special, there are inevitable times of friction, differences of opinion, and perspective.

Eleanor Roosevelt described a family-like attitude in the relationship: “Though there is always in this country a certain amount of criticism of and superficial ill feeling toward the British, in time of danger something deeper comes to the surface, and the British and we stand firmly together, with confidence in our common heritage and ideas.”

On their part, the Brits do take great delight in denigrating American mass popular culture. You’ll often hear them discussing it in line at McDonald's or KFC. And despite what they say, they like our movies as much as we like theirs. They do appreciate us for our popular culture more than they admit. They love Disney World and our beaches, our open hospitality, and our delighted, heavy support of their tourism industry.

What we have drawn from our British roots, what we have learned from them, however, runs far deeper than what they have learned from us. In some sense, we look upon Britain as an aged parent, while it has always tacitly regarded us (along with Australia, Canada, and New Zealand most notably) as one of the adult children. That we could teach the parent serious new tricks is not a thought that comes easily to them.

At this point in our mutual history, though, there really is a lesson that Britain could learn from this rebellious child. Much has been written about Britain’s ongoing soul-searching for its identity. While Great Britain has never conceived of itself and the union of its peoples as a federation, America solved the dilemma of its identity this way.

When our first 13 colonies evolved into fledgling states, it was not without much deliberation and compromise that we molded the United States by confederation. Though 300 years old, the union that is the UK today was not so thoughtfully or mutually entered into by the principality and kingdoms of Great Britain.

Americans today feel no conflict in loyalties between our state and national identities. We are both American and North Carolinian or Minnesotan. No Michigan vs. Ohio State football game evokes less enthusiastic partisan rivalry than Scotland vs. England in the Seven Nations, but the identity that underlines that rivalry in no way conflicts with the mutual identity Ohio and Michigan’s citizenry share as Americans.

USA v UK

A federation

Great Britain is a federation, whether or not it thinks of itself that way. Increased self-governance in Wales and Scotland would be easier for all parties to grow with if the British had a better intuitive understanding of the idea of federation. The devolution of governance to the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish Parliament has been a bumpy road to say the least. The nation has not looked for the model that America might humbly provide.

The Scottish National Party, whose sole political plank is Scottish independence, has been the biggest beneficiary from the political collapse of the Labour Party. Wales’ nationalist party, Plaid Cymru, has proven a competent power in the Welsh Assembly. With questions of England’s own self-governance still unanswered, the UK faces more constitutional questions and changes ahead.

The Balkanization of Britain makes no sense at all. The practical considerations alone are mind-boggling. The capacity of Scotland, let alone Wales, to survive independence economically is highly questionable. The replication of government bureaucracies would be immensely costly to taxpayers in all three countries.

Would an independent Wales and Scotland inherit EU membership (or want it)—now giving Great Britain three votes and vetoes? NATO membership? Separate embassies throughout the world? Where is Northern Ireland left?

And certainly, the dissolution of the United Kingdom would result in a diminished voice in the world and European affairs for any smaller resulting nations.

Unhappily, Scottish and Welsh nationalists are romantic tribalists. Their message makes as much sense as the lonely Confederate diehard still insisting the South shall rise again. The conflicts of identity and territory over which feudal lords and overlords contested belong to ancient medievalism. The Great British union is older than America, with roots intertwined well before that.

If shared social and political values, language, institutions, and history bind a kinship of the English-speaking peoples, how much more numerous and significant are those ties that unify Scotland, Wales, and England? They have fought under the same flag, rooted for the same Olympic team, and watched the same BBC for generations. Their national accomplishments have been the pride of a shared history for centuries.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Read more

Take a page from America's book

Rather than expending Britain’s emotional, financial, and political resources in the palaver over whether to stay a Union, the spokespersons of Westminster’s constituent states would be far better served polishing the mechanism of their federation and finding it something to celebrate rather than argue about.

America’s historic failures are an open book, but Britain can take a page from our success. While across the pond, our favorite sceptered isle is shared by three states, America is a federation of 50 states across a continent with people at least as diverse as the British.

Our charter documents and the dynamic of our society may provide some suggestions on how to work together as states and as people without a shared history going back forever. Taking pride in being British is not disloyal to be Scottish or Welsh or English, but it is a loyalty to be proud of. Besides, though we Americans may have personal loyalties to somewhere particular on the island, it is with Britain and the British that we former colonists have that special relationship.

British Heritage supports the Union.

* Originally published in July 2016. Updated in 2024.

Comments