What could be more English than a game of cricket? Just make sure you have a few hours to spare.

[caption id="HowzatThatscricket_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© EUROPEAN SPORTS PHOTOGRAPHIC AGENCY/ALAMY;

AFTER SPENDING AN HOUR at Lord’s, cricket’s London headquarters, Groucho Marx famously quipped: “This is great. When does it start?”

American anglophile Bill Bryson was more explicit, writing, “It is not true that the english invented cricket as a way of making all other human endeavours look interesting and lively; that was merely an unintended side-effect.”

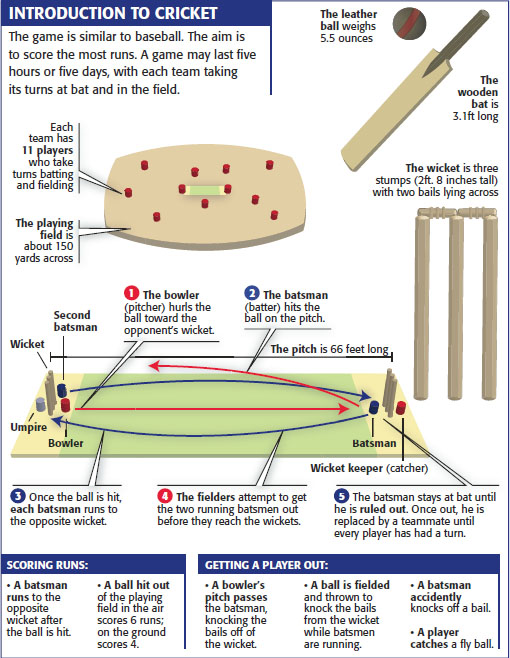

He forgot to add it is the only team game where one team has all its members on the field while the opposition has only two members in play at any one time. And that a game can last five days and still end in a draw.

The heart of cricket beats to an 18th-century beat. Sports codified in Victoria’s reign—soccer, rugby, tennis—all pump to a modern rhythm, suitable for the television age. Cricket, on the other hand, beats to the rhythm of farm work, the harvest and long hours spent under a summer’s sun.

Much has been written about exactly where and when cricket started. The stunning village of Hambledon, Hampshire, is the acknowledged birthplace, giving it a reputation as “the cradle of cricket.” Still in existence, its cricket club is thought to have been founded about 1750. In the 18th century, the club played an England XI on 51 occasions, managing to beat the national side 29 times.

The center of the cricketing world is a ground opened in 1814 in St. John’s Wood, London. Lord’s Cricket Ground is home of Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), founded in 1787. Nothing to do with the House of Lords, it is named after founder Thomas Lord, a player tasked with finding a home for the MCC.

Unlike other sports, cricket doesn’t have “rules;” instead MCC established its first “laws” of the game in 1788. There are currently 42 laws, which outline all aspects of how the game is played and won, from how a batsman is dismissed to specifications on how the pitch is to be prepared and maintained.

ALL AT SEA

The annual Brambles cricket match can sometimes last only one hour. Its brevity is explained because it takes place in the middle of the Solent, midway between Southampton and the Isle of Wight, when the tide reveals a small sandbank. Dozens of boats containing participants and spectators wait around the bank for the sea to subside. As soon as the bank appears, it’s over the sides of the boats as the stumps are put up and the match gets under way. Many of the competitors dress in cricket whites and a pub is established to serve drinks. There is always a dinner held on the return to the mainland.

[caption id="HowzatThatscricket_img1" align="aligncenter" width="727"]

ISTOCK VIA THINKSTOCK;

[caption id="HowzatThatscricket_img2" align="aligncenter" width="720"]

© EUROPEAN SPORTS PHOTOGRAPHIC AGENCY/ALAMY;

St. John’s Wood is no distance from the West End, and plays hosts to first class and Test cricket matches with opponents from around the globe. But it is not just a venue for the professional game. Village teams from Rockhampton, Gloucestershire, and Cleator, Cumbria, contested the Davidstow Village Cup Final at Lord’s in September. The two amateur teams had progressed from the semifinals in August and had a month to build up to the biggest match of their lives.

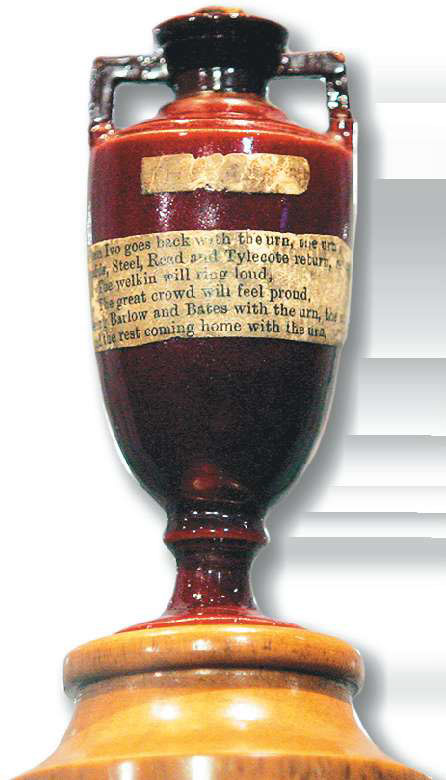

No mention of Lord’s would be complete without mentioning the most significant artifact in world cricket, which is held at the ground: a 4.3-inch-high terracotta urn containing the burnt remains of cricket bales, the wooden pegs that cross the cricket stumps.

On August 29, 1882, Australia shocked England by defeating it in a cricket match played at the Oval, London’s other great cricket ground. Such was the consternation created by this result that an obituary notice appeared in the Sporting Times: “In affectionate remembrance of English Cricket which died at the Oval on 29th August 1882. Deeply lamented by a large circle of sorrowing friends and acquaintances. RIP. NB. The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia.”

Thus was born “The Ashes,” an annual do-or-die series of matches between Australia and England that continues to this day. In 2013’s Ashes, the triumphant English team celebrated with all the razzamatazz of a F1 win or the Rose Bowl, yet the center of the celebrations was still just a little urn.

[caption id="HowzatThatscricket_img3" align="alignleft" width="1024"]

© SIMON DACK/ALAMY;

[caption id="HowzatThatscricket_img4" align="alignright" width="857"]

© LAST REFUGE/ROBERT HARDING WORLD IMAGERY/CORBIS

Unlike soccer and rugby, cricket can only be played in the finest conditions. The slightest rain, a darkening sky, means play stops. And this in a game played in an English summer! When the call for rain goes up, players dart for the dry sanctuary of the cricket pavilion, while viewers unfurl their umbrellas.

Gentlemen and Players

Given its age and complexity, it is no wonder that cricket is known for its rich terminology. One of the most interesting words the game has given to English speakers is “howzat,” a corruption of “How’s that.”

In one of the game’s more curious laws, an umpire is not allowed to rule a batter out unless the opposition appeals. The exception is when the out is so obvious, such as when a shot is caught by a fielder and the batsman walks off of his own accord. This has led over the decades to the appeal “how is that?” becoming abbreviated to “howzat?”

Luncheon, as the name suggests, is the first of two intervals taken during a full day’s play, and normally starts between 12:30 p.m. and 1 p.m. A 20-minute break for tea is normal around 3:30 p.m.

With roots dating back to Jane Austen’s England, it’s no surprise that cricket has been long associated with (and enjoyed by) the gentry and upper classes. This was most obvious in the split between “gentlemen” and “players.” With the English upper-class worship of amateurism, gentlemen played for fun, while the professional players played for money, earning their livelihoods from playing. The last Gentlemen v. Players match was held in 1962, after which all players were deemed to be professional.

Fans of the unflappable valet who constantly rescues his well-meaning, upper class twit of a master may not be aware that cricket-mad, master storyteller P.G. Wodehouse took the name Jeeves from talented bowler Percy Jeeves, who died fighting on the Somme in 1916 in World War I.

Summer sun

© TIM WIMBORNE/REUTERS/CORBIS

World War I poet Edmund Blunden wrote, “Cricket to us was more than play; / It was a worship in the summer sun.” In the 1892 poem “Vitaï Lampada,” Henry Newbolt referred to how a schoolboy, a future soldier, learns selfless commitment to duty in cricket matches at Clifton College, ending his work: “Play up! play up! and play the game!”

Is there any validity to the idea that cricket has something of the soul of England and the English in it? it is a slow-burning pleasure for its followers. The game speaks of a preindustrial world where farm workers could play the sport in the fields after the harvest; where an afternoon is whiled away drinking local beer as a local team takes on a neighboring village team in friendly rivalry.

The soul of cricket is gamesmanship. A cricket audience is meant to be even-handed, acknowledging deft moves from both teams, while players never disagree with officials. Batsmen are never meant to disagree with an out decision; it is taken as very bad form. So ingrained is this idea that when, away from the field of play, someone does something underhand, the cry “that’s not cricket” can be heard. This spirit was brought into comic focus in World War II when a plan to infect Adolf Hitler with yellow fever by a British officer was knocked back by the War Office with the verdict that it “wouldn’t be cricket.”

Visiting England in the summer months, do take in some of a cricket match. You may not understand the laws, and you may wonder at any team game where players wear white all day and don’t get any dirt on the clothes, but you will surely have a glimpse of the soul of England. Howzat!

Comments