The Aran Islands in the rough seas off lreland’s west coast are moored like three listing ships of stone, with cliffs windward and beaches alee in the rough seas.

[caption id="IslandsApart_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="876"]

Randall Hyman

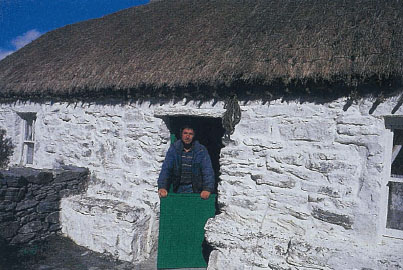

[caption id="IslandsApart_img1" align="aligncenter" width="443"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img2" align="aligncenter" width="170"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img3" align="aligncenter" width="172"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img4" align="aligncenter" width="169"]

Randall Hyman

“we call ourselves islanders,”

Enda Gill, a B&B hostess on Ireland’s Inishmore Island proudly tells me. “People from the mainland are Irish.”

But as different as these legendary isles are from the mainland, they differ nearly as much from one another. Visiting all three is like sampling a trio of desserts after a solid meal of touring Ireland’s mainland. I start with the biggest mouthful first, eight-mile long Inishmore, Irish for Big Island, population 900.

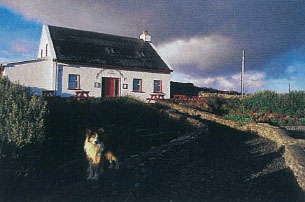

“Island life, it’s still very difficult,” says Gill, “but it’s getting easier.” There was no electricity here and little transportation to and from the mainland as recently as 20 years ago. Today electricity is supplied by undersea cable, and tourists pour through the main town of Kilronan aboard regularly scheduled ferries and planes throughout summer. Inishmore is the most heavily visited of the three Aran Islands, and, consequently, the most commercial.

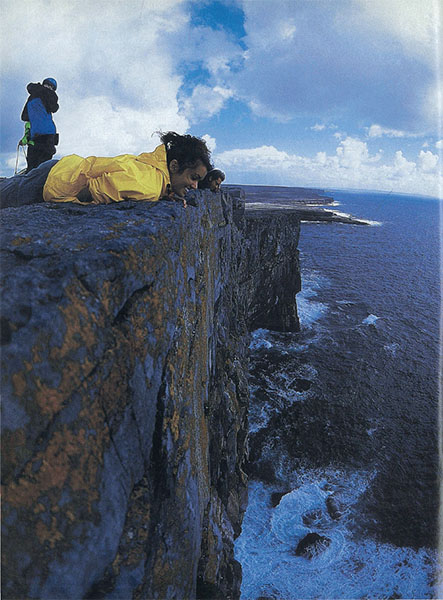

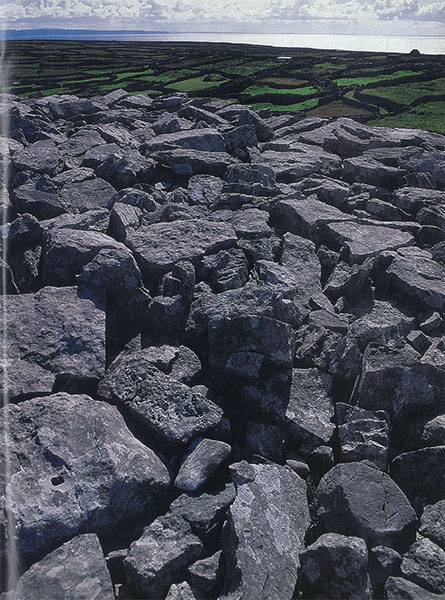

Besides the heritage museum, shops, and pubs of Kilronan, a “must see” for one-day visitors is Dun Aengus, the most spectacular of four stone forts scattered across the island. The approach is steep, and row after row of pointy boulders form a crude defence line outside the far wall, a stone version of the chevaux de frise of a later age made of iron spikes.

This 2000-year-old structure perches atop a 300-foot ocean cliff, as “on the edge” as it gets. No wall stretches along the sheer precipice that edges one side of the fort. Some say that the seemingly missing half of the semicircular fort vanished with the ever-crumbling cliffs, a theory apparently dismissed by visitors who belly-crawl to the edge to look straight down on the crashing surf far below. I join them, my stomach uneasy. I crawl back from the brink to explore the fort’s solid parts. The meticulously fitted, concentric stone walls seem untouched by the ages, and the courtyard appears paved in some places.

This “pavement” is the limestone base that makes the islands look like giant concrete pourings from some angles. Closer inspection reveals a series of limestone terraces and a gridwork of man-made pastures half concealed by stone walls. For centuries islanders have laboriously pried rocks out of fields, then fertilized the thin topsoil with burnt kelp mixed with sand. Never short of rocks, men have built some 900 miles of stone walls.

[caption id="IslandsApart_img5" align="aligncenter" width="434"]

Randall Hyman

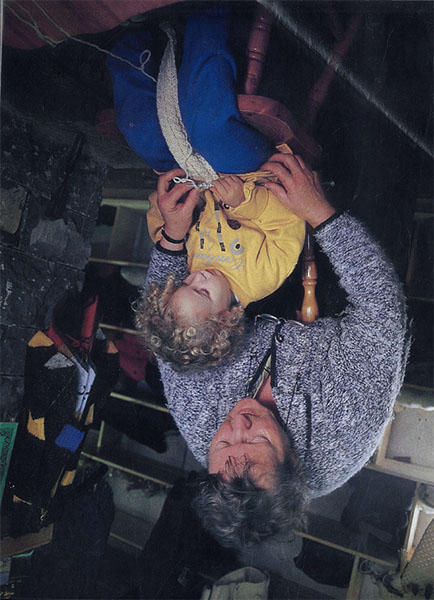

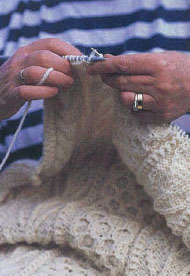

I follow the long hill down from the fort and stop to shop at a thatched-roof woollen shop. Here I meet Maggie Flaherty giving an American girl impromptu lessons in knitting. “That’s it, that’s the pearl stitch,” she beams. “Maybe she’ll be knitting an Aran sweater some day. The young girls, they don’t take so much to it these days.”

Aran sweaters are perhaps the best known and least understood of all the islands’ symbols. Distinctive for their richly cabled designs, the sweaters are a 20th-century innovation. Homespun tweed jackets and crocheted shawls were the rule before the 1900s, with knitting consigned mainly to socks. Sweaters, or ganseys (jerseys), first appeared with the arrival of seasonal fishermen from Scotland and the Channel Islands at the turn of the century. Once island women learned how foreigners used a third needle to create cabled patterns, they went wild with their own fanciful Celtic designs.

Author John Millington Synge, who won fame writing about the islands, is often accused of propagating a popular myth that drowned fishermen were identified by the patterns on their sweaters. In his play Riders to the Sea, Synge tells of a girl counting stitches on a sock sent to her after being removed from a drowned sailor already buried on the mainland.

[caption id="IslandsApart_img6" align="aligncenter" width="193"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img7" align="aligncenter" width="409"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img8" align="aligncenter" width="190"]

Randall Hyman

“I put up three score stitches, and I dropped four of them,” she cries upon confirming the socks are those she knitted for her brother. Synge based his writings upon lore collected while he visited the islands for several weeks each year from 1898 to 1902. He was among the first of a long line of writers, photographers, and filmmakers to make the Aran Islands their subject throughout the 20th century.

i find passages by synge and other writers

emblazoned on walls at the Aran’s Heritage Centre amid exhibits ranging from geology to ethnology and hourly showings of Robert Flaherty’s 1934 docudrama, Man of Aran. Having just crawled along the cliffs of Dun Aengus, I am struck by a line from Stones of Aran by contemporary writer Tim Robinson: “However, it is wise to keep clear of the brink especially in gusty weather, an islander warned me—and I pass on the advice to beware of ‘the suckage,’ for a sort of hurricane could pick you up and whirl you over, even if you weighed ten tons.”

I keep this in mind days later when I move on to Inishmaan, Irish for Middle Island, population 200, and visit Synge’s Chair. Padraic Flaherty leads me along a cliff to a stone seat surrounded by a small rock wall where Synge often sat and wrote. Its westerly view is perfect for admiring sunsets and storms. We walk on to another overlook of sheer cliffs and rocky shore.

“inishmaan’s rusticity and sparse attractions allow one to hear the silence, watch the waves, and meet the people.”

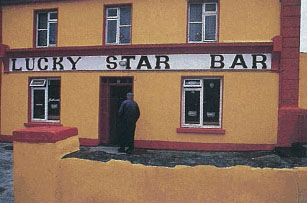

“We used to play at the bottom as kids,” Flaherty muses. “We’d climb down where we could. It wasn’t safe and I wouldn’t do it now.” Older and wiser, Flaherty has more at stake these days. He and his spirited wife, Meg, a Virginia transplant, run the only pub on the island. Without Flaherty, islanders might go thirsty.

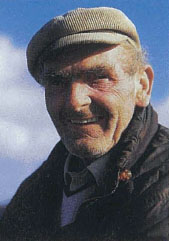

“I think he prays for droughts,” laughs octogenarian Liam Davis when we meet him on his customary walk past Synge’s Chair. “This summer was a terrible drought. We were down to one day a week for water. Padraic did a great business!”

Rains regularly soak the nearby mainland, but the Aran Islands miss much of the precipitation released by the interplay of land and sea. The limestone worsens the problem by keeping the rainfall from soaking in.

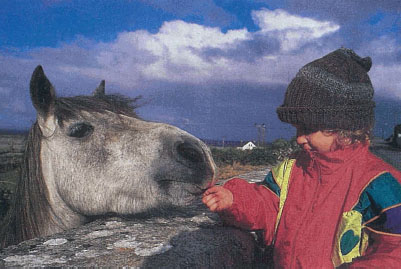

Luckily Inishmaan is the least trafficked of the Arans, so tourism doesn’t tax the water supply as much as on the other islands. The very qualities that make Inishmaan less appealing to some help preserve its authenticity. No gift shops, no horse-and-buggy tours or the like—its and sparse attractions allow one to hear the silence, watch the waves, and meet the people.

[caption id="IslandsApart_img9" align="aligncenter" width="401"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img10" align="aligncenter" width="403"]

Randall Hyman

There aren’t many. “When I was a boy in the school there were 90,” says 50-year-old Michael Concannon one evening as we wander Inishmaan’s main road in his small pickup. “Now there are only 16.” After passing Teach Synge, the recently renovated cottage museum where the author stayed during his visits, Concannon points out a larger house along the road. “There’s the house where I was born. A thatched cottage with three bedrooms. Eleven of us in the family. We were quiet!”

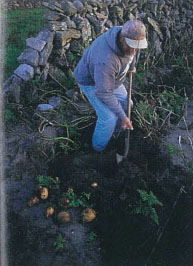

Being quiet is an island trait, which may explain why 25 per cent are unmarried. Concannon invites me to a big helping of quiet along with fresh produce when we go to dig up potatoes in the lush fields below the village. The world is hushed as a golden sunset bathes the still evening. Nary a soul is here. We walk through a maze of boxed-in paddies, turning right, left, left, right, and onward through a series of gates and gaps in the endless stone walls. I am happily lost on Inishmaan.

We finally stop at one of scores of paddies in the maze. This plot has been in Concannon’s family for generations. He digs up some large white spuds while I study the sandy, loamy soil and wonder at the sweat his ancestors invested in creating this little garden All these fields were covered in stones at one time, and there was little topsoil.

[caption id="IslandsApart_img11" align="aligncenter" width="445"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img12" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

Randall Hyman

” Don’t eat too many potatoes, now,” Concannon advises me later as we part at dusk in the village and he hands me a bag. “You won’t be able to sleep tonight.”

I go easy on the spuds at dinner and rise early next morning to rush down to the pier near Concannon’s home. The last lobstermen of the season are launching their currachs, traditional wood-frame rowboats usually covered with tarred canvas. These modern ones have Fiberglas skins and outboard motors. They still seem too fragile and precarious for the treacherous North Atlantic, but their lightweight, narrow design lends great agility as they ride waves like dolphins.

“Currachs are dangerous,” Concannon tells me. “My brother-in-law, he got drowned in one in 1980. He was 17. He was out there at the other end of the island and a wave just caught him. He was a good swimmer too. Sure the sea’s tough sometimes.”

The same can be said for island life in general, even in this modern age. Hardships like drought, power outages, and violent weather, though common elsewhere in the world, are particularly tough on a small, isolated island with few natural resources.

despite it all, many former islanders

are actually returning home to start families—especially on Inisheer, Irish for Small Island, population 300. The next afternoon I catch a ten-minute ferry ride to this smallest isle of the Arans and step into a world completely different from Inishmaan. Shops, restaurants, and horse buggies await the many tourists who arrive each day from the town of Doolin in County Clare. Of the three islands, Inisheer has the closest ties with the mainland just six miles away.

JOURNEY NOTES

Getting About: Ferries run from Rossaveal in Connemara on Island Ferries and from Doolin in County Clare on Doolin Ferry. Air service departs Connemara Airport at Spiddal on Aer Arann. For schedules and fares see: www.aranislandferries.com • http://homepage.elrcom.net/-doolinferries • www.aerarann.ielschedule-a.html

There are no rental cars available on the islands: transportation is by rental bike, mini-bus, or horse cart.

Accommodation: All three islands have many B&Bs but few hotels. On Inishmore stay in Kilronan for easy access to restaurants and shops. On Inishmaan, Vilma Conneely’s B&B (tel: 099 73085) has excellent meals and lodging. On Inisheer, Una McDonagh’s Ard Mhuire B&B (tel: 099 75005) near the pier offers a cosy atmosphere and warm hospitality.

[caption id="IslandsApart_img13" align="aligncenter" width="305"]

Randall Hyman

[caption id="IslandsApart_img14" align="aligncenter" width="307"]

Randall Hyman

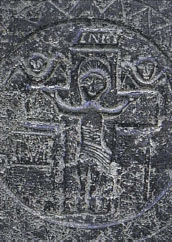

O’Brien’s Castle dominates this small island. It’s a 15th-century structure named for the family that built it and ruled the Arans for 450 years. The castle stands atop one of Inisheer’s highest spots near an 18th-century signal tower, with 10th-century St. Kevin’s Church at the foot of the hill. A half-day hike circles the entire island of Inisheer, past a 1960 shipwreck, a lighthouse, and a holy well.

I arrive on cattle-market day as an occasional farmer chases two or three cows through the village down to the pier. A buyer from the mainland awaits them. As deals are closed, farmers load the animals into cages and forklift them to a small cargo ship. It is quick and efficient, but not so many years ago islanders roped cattle by their horns and towed them through the sea behind currachs to load them offshore. Life has changed dramatically in a short time.

Perusing a 1971 National Geographic article about the Aran Islands with B&B owner Una McDonagh, I see how far locals have come. There are no telephone or power lines in any of the pictures, and the scenes of daily life recall an Ireland of yesteryear. McDonagh flips the pages to a portrait of an Inisheer family posed around a fireplace. In the photo a little girl cowers in her mother’s lap. The family is McDonagh’s, and she is the little girl. I sit with her and her mother before the toasty hearth in the room, now greatly changed, where the-picture was taken.

“I remember the photographer had a tripod set up outside the door right there and I was scared,” laughs McDonagh while her two-year-old son does some further rearranging of the room. “My brother and his friends told me claws came out of the camera and grabbed you.”

Modern islanders are more worldwise than a few decades ago, and tourists with cameras attract little attention. The children I meet along Inisheer’s renowned swimming beach fear neither me, my camera, nor the icy North Atlantic waters. I’m wearing a warm jacket against the evening chill as I snap a few pictures of them, then watch in amazement as they strip to bathing suits and sprint down the sandy shore. They plunge headlong into the gentle surf with spirited hoots and hollers, embracing the sea that for ages has punished and preserved the Aran Islands.

Comments