[caption id="LandofMyFathers_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

THE STORY OF THE WELSH NATIONAL ANTHEM

THE FIRST DAY OF MARCH IS A SPECIAL OCCASION for Welsh people everywhere. It is the feast day of St. David, patron saint of Wales. It commemorates the date on which he died in AD598, when, his biographer records, “He entered into heaven where he was received by a great company of angels.”

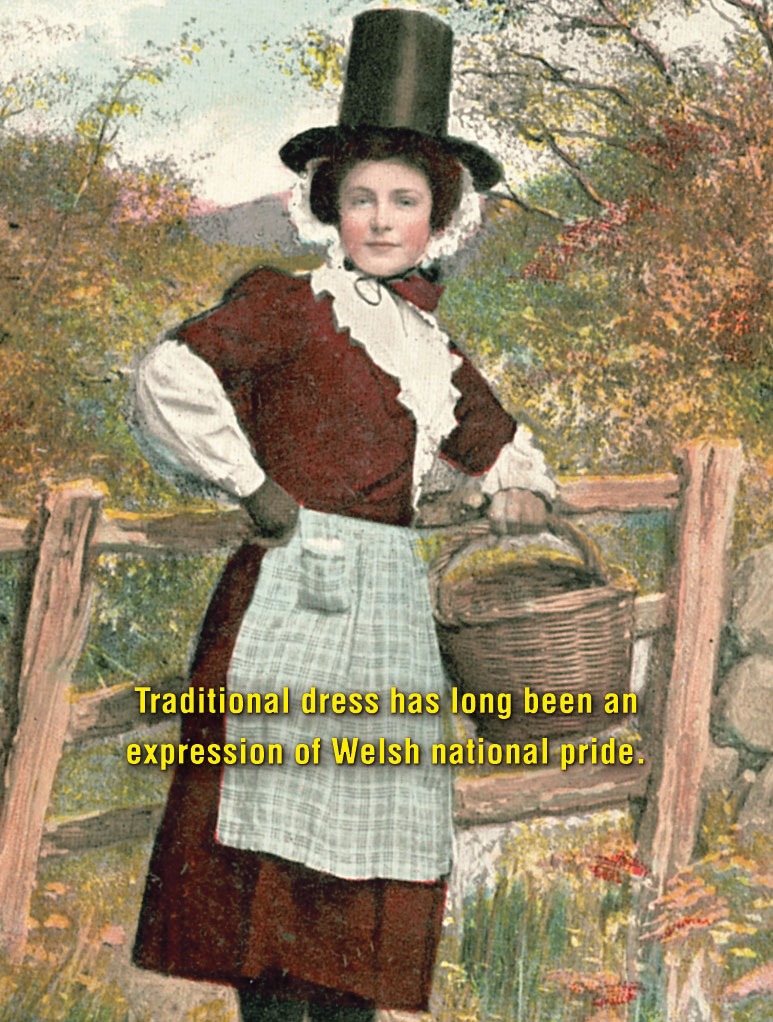

This national day has long been fervently celebrated by the Welsh, and until the Reformation St. David’s Day was observed as a church festival. During the 16th century, it was the custom of King Henry VII, himself a Welshman, to pay generously for a feast for his Welsh bodyguard on St. David’s Day. Shakespeare, who is said to have had a Welsh schoolmaster as a boy in Stratford-upon-Avon, refers to Welshmen and the leek that they wore on “St. Taffy’s Day.” In more modern times, it is the custom in towns and villages across Wales to celebrate this special day in pubs, singing festivals and eisteddfods where the leek and daffodil, the country’s national emblems, are prominently seen.

In all those celebrations, there will be enthusiastic renderings of the Welsh national anthem, “Land of My Fathers.” For Welshmen everywhere, the song epitomizes the special affection for their homeland and all that it represents to them. Few people, however, are aware that this renowned and much-loved anthem was composed just a century and a half ago.

[caption id="LandofMyFathers_img1" align="aligncenter" width="773"]

COURTESY OF DAVID WATKINS

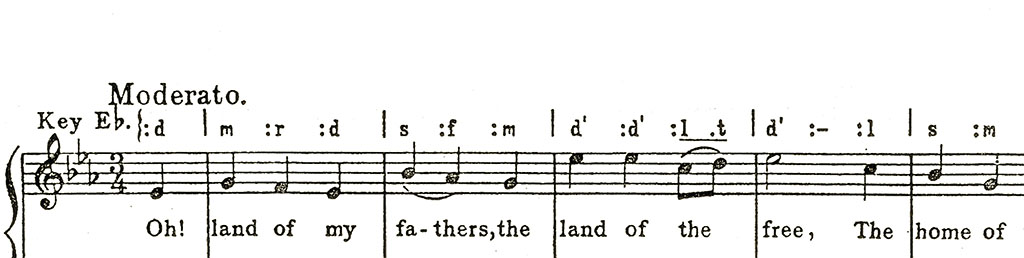

The anthem was born in the town of Pontypridd, at the base of the Rhondda Valley. It was the result of a collaboration of father and son, Evan and James James. The father, Evan, was a weaver and wool merchant. His son James was an ardent music lover and an accomplished harpist. They both lived near the small wool factory on Mill Street in Pontypridd.

A well-informed account of the composition of the piece is provided in a letter by one of James James’ five sons, dated December 4, 1910, now kept in the Cardiff Central Public Library. He records: “I have often heard my father say that on a Sunday afternoon in the month and year [January 1856], he went for a walk up the Rhondda Road, and that the melody came into his mind. Returning to my grandfather’s house, but a few doors from his own, he said: ‘Father, I have composed a melody which is in my opinion a very fitting one for a Welsh patriotic song. Will you write some verses for it?’”

James then played the melody on his harp, and his father was so struck by the emotion it inspired in him that he began to scribble words suitable for it on a slate that he kept near him. He completed the first verse that day, and wrote the second and third stanzas during the course of the same week.

The original holograph of the words and music in the handwriting of James James can be seen today in the manuscript department of the National Library of Wales at Aberystwyth. A study of the manuscript indicates that the words are those still sung today as the national anthem, but that today’s melody does differ slightly from the original composition.

Originally, the James’ song was known by the prosaic title of “Glan Rhondda,” commemorating the place of its composition. It was first included in two collections of unpublished Welsh airs submitted in a competition at the Llangollen National Eisteddfod of 1858. The melody and lyrics were highly praised by the adjudicators, and a prize and medal were awarded to the father and son. Three years later, the song was published in an anthology called Gems of Welsh Melody. Soon, it was to be called “Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau,” “Land of My Fathers,” from the opening words of the song.

“Land of My Fathers” was sung for the first time in public at a small chapel in a village near Pontypridd. The soloist was a 16-year-old girl named Elizabeth John. The same year, James James sang it himself, accompanied by a harp, at the opening ceremony of an eisteddfod at Pontypridd. By the end of the 19th century, the song was popularly regarded as the Welsh national song. Every prominent meeting where Welsh people congregated included a singing of the anthem. Eisteddfodau held all over the land made the song a part of their proceedings.

Early in the 20th century a fund was established to perpetuate the memory of Evan James and James James. All Welsh people were invited to contribute. The wording of the appeal read: “Guineas, half-guineas, and smaller sums will be welcomed from those who can not afford more: larger subscriptions should come freely from others—but the response should be immediate.” When the fund closed in 1914 more than £1,000 had been collected.

[caption id="LandofMyFathers_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

MARTIN JONES/CORBIS

A spot was found at Ynysangharad Park in Pontypridd—barely 100 yards from the place in Mill Street where the anthem was composed—for the sculptor Sir W. Goscombe John to begin his work to commemorate the “unhonoured and unsung” benefactors of Wales. The years of World War I and the depression that followed hindered active progress. It wasn’t until July 23, 1930, that the lifelike bronze figures, a woman representing poetry and a man holding a harp, were unveiled in the park. An inscription in both Welsh and English at the base of the figures outlined the story of the composition of “Land of My Fathers.”

On that fine summer afternoon, some 10,000 people sang the anthem, accompanied by the band of the 5th Welsh Regiment. The surrounding hills reverberated to the stirring composition as a tribute to the two men whom the nation now honored.

Comments