[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1009"]

Jim Hargan

Life on the Merseyside Quays

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img1" align="aligncenter" width="315"]

Jim Hargan

Industry & Empire Fifth in a Series

By the early 19th century, the city of Liverpool looked to surpass London as Britain’s premier port. Facing westward toward the Atlantic, Liverpool controlled trade with the New World in the way that east-facing London controlled trade with Europe. But trade with the New World was explosive, while war and the Depression had caused trade with Europe to stagnate.

While Liverpool had to split the New World traffic with Bristol, Plymouth, Glasgow and a host of lesser ports, it wasn’t much of a split. Liverpool’s docks and warehouses moved most of Britain’s New World trade in cotton, timber, manufactured goods, luxury goods and humans.

Liverpool’s innovative port technology, lucrative merchants and ready supply of laborers (hoping to make passage money to the New World) contributed to its success—so much so that in 1845 Liverpool became the site of the world’s first fully modern seaport: Albert Dock.

In the early 18th century, British port technology was basically medieval. A ship would offload its cargo straight to a riverbank, improved for this purpose by forming it into a wood or stone wharf known as a “quay” (pronounced “key”). Because ships unloaded sideways, they had to pull up parallel to the quay, so a given length of river could handle only a few ships at a time. Once the ship had docked, unskilled laborers would unload its cargo by hand and stack it on the quay in the open, exposed to weather and pilferage.

Liverpool will hold the title of European Capital of Culture for 2008. Once again, Albert Dock has worked its magic

Customs officials were supposed to levy tariffs on the stacked goods, but merchants could avoid both theft and tariffs if they moved their goods quickly enough; the merchant would send his foreman to the quay, who would quickly round up a crew of about a dozen laborers from the men hanging about and have them move the cargo to the merchant’s warehouse, typically located behind his nearby house.

Oceangoing vessels faced some additional complications. First, they docked on tidal rivers (such as Liverpool’s River Mersey), so they had to wait for a high tide, then dock and finish cargo handling before the tide went out. Liverpool’s spring tides can reach 30 feet, so a ship that stayed moored too long could end up stranded on the mud, lying on its side. A busy port like London’s or Liverpool’s could easily run out of parallel quayside berths long before all of the waiting ships could be serviced. Ships could queue for berths for as long as three weeks.

As the 18th century wore on, the big ports became clogged as too many ships and too many merchants tried to fit into too small a length of quay. The quays became dirty, smelly, noisy and teeming with vagrants and low-lifes. Merchants moved their houses away from the quay, leaving the quayside to form into a crowded district of warehouses, low-rent housing and taverns for the sailors who flooded in at every high tide.

As quayside land became more expensive, private warehouses became taller—as much as seven stories, the practical limit of unreinforced brick construction. These warehouses had a front gable, with a recess running roof-to-ground underneath it. When the foreman and his dozen pickup laborers arrived with a cartload of cargo, laborers would go to a small attic compartment to hand-operate a hoist, one of the most dangerous and unpleasant jobs on the docks. Others would manhandle sacks and barrels of goods onto the hoist and into the bays on the proper floor, for floor-to-ceiling stacking. Sacks and barrels were just big enough to be handled by a single strong man.

Fire was a major problem. These tall, skinny warehouses had wooden floors and roofs, and were often used to store highly flammable materials such as pitch and flour. Once a fire started, a warehouse would become a chimney. Anyone inside would die, the stored goods would be lost and the fire would spread to adjacent warehouses. Not infrequently, whole blocks were lost.

Customs was another problem—at least for the government. No longer could goods be rated on the quayside, as merchants rushed them into private storage. Instead, customs officials would certify certain private warehouses as approved repositories of yet-to-be taxed goods, and these “bonded” warehouses were the supposed first destination of the goods. With more than 200 bonded warehouses scattered all over Liverpool, the system worked poorly for the government—but was great for tax-dodging merchants.

The docks, built specifically for loading and unloading ships, underwent significant changes as the number and size of boats using them grew. In Liverpool, with its 30-foot tides, you couldn’t simply throw a wooden structure over the water. Its docks had to be put on built-up land dredged from the water in front of the quay, moving the shoreline some distance out into the tidal waters of the Mersey River. The new land surrounded a pool big enough to allow additional ships to berth. This pool was separated from the shipping channel by locks. At high tide, ships came in, berthed and started moving their cargo. As the unloading could continue. When the tide returned, the ships would be ready to leave, to be replaced by a new flotilla.

A new dock was a big investment; the value of shipping had to grow a lot in order to make it worthwhile. Thomas Steers built the world’s first such commercial wet dock in Liverpool in 1715. By the end of that century, Liverpool had seen a 3,900 percent increase in the number of ships visiting per year, and wet docks spread up and down the Mersey’s Liverpool bank. Seventy years later, the number of ships rose another 375 percent, while the size of those ships doubled and doubled again. In 1871 wet docks occupied seven continuous miles of the Mersey’s banks. Of these, the 1845 Albert Dock was neither the first nor the biggest. It was merely the greatest—the first truly modern shipping facility in the world.

Technology, however, is only half of Liverpool’s port story. There’s a human side to the story as well. Let’s start with the Triangle Trade. This consisted of shipping a cargo of English goods to Africa and using them to buy a shipload of slaves for a healthy profit; then shipping the slaves to the New World, selling them for a healthy profit; then filling the holds with cotton, tobacco, sugar or rum for sale back in England at, yes, a healthy profit. Liverpool’s merchants became highly skilled at shipping large human cargos with minimal loss. The vast profits from this trade funded the docks, canals, warehouses, factories and other trade improvements that made Liverpool into England’s dominant export city by 1800.

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img2" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img3" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

In 1807 the British government banned English slave trading. This was not the disaster for Liverpool’s merchant elite that one might expect. The United States—the Liverpool slavers’ best customer—decided to ban its participation in the international slave trade by 1808, and slave profits were going down. The United States was now able to breed its own slaves cheaper than importing them. Fortunately, the Liverpool merchants had already found a great new substitute: emigrants.

Drastic changes had overcome the Gaelic fringe of Scotland and Ireland, and its peoples were fleeing. Economically backward even by medieval standards, these Celtic peoples had been practicing a purely subsistance way of life with a tribal society, occupying vast areas of moorland while producing very little by way of money rents. Despised by the English-speaking peoples, the Gaels were widely seen as a barrier to progress. Starting in the 1780s, English-language landlords in both Scotland and Ireland moved the Gaels off their farms to rocky coasts nearly devoid of soil, a period known as “The Clearances.” Their method had a cruel efficiency behind it; the Gaels would be forced to improve this worthless land or die, giving the landlords profit without cost.

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img4" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Mary Evans Picture Library

The Gaels survived. They were never very good at fishing—about what you’d expect from people who had been mountain shepherds for 30 centuries. Instead, they came up with a three-pronged approach to not dying. One, a family would create great raised beds of seaweed compost, and use these to grow potatoes. Two, the young men would leave home to find jobs and send home money. Third, some families would emigrate to North America, relieving somewhat the pressures on the land.

Remember all those unskilled laborers the warehouse foremen would gather up to move cargo? That’s where they came from. Some of them wanted to send money home; others were trying to raise the steep payment to buy a berth in a Liverpool transatlantic ship.

In 1845 the situation became much worse. A fungus infected Ireland’s potato beds, reducing a field full of roots to a stinking mass of black goo in less than a week. It spread to Scotland the next year, and remained out of control for another decade. During the Great Hunger that ensued, about a half-million Gaels died directly from starvation-related diseases, and 2 million more became refugees. Gaels flooded into Liverpool, desperate for passage to North America.

Liverpool became the emigration center of Europe. Moving desperate Scots to the New World was immeasurably superior to hijacking Africans. Not only was it legal, but also the merchants could charge a lot for it, get paid in advance, and not take a hit to their profits when their cargo died. Uncounted refugees descended upon Liverpool, scrounging for pickup work to raise passage money while trying to survive some of the worst housing conditions in Europe.

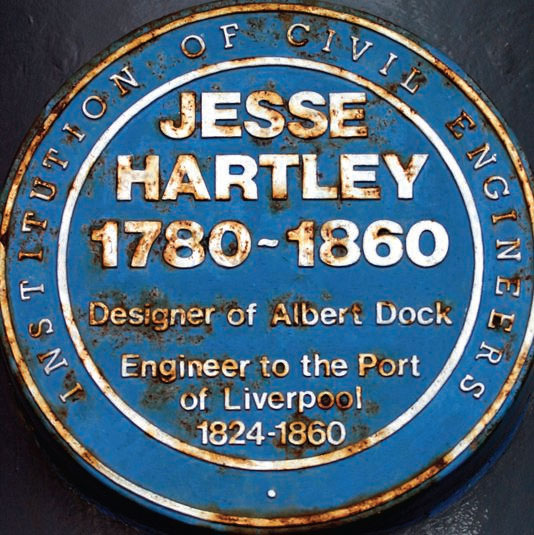

In this period of turmoil, Jesse Hartley emerged as Liverpool’s great dock builder. Liverpool’s town corporation (sort of a combined municipal government, port authority and merchant guild) appointed Hartley as its chief dock surveyor in 1824, and he remained in that post until his death in 1860 at age 80. By 1842 Hartley had knocked the chaotic Liverpool port into some semblance of order, and was ready for his masterpiece: Albert Dock.

Hartley built Albert Dock in central Liverpool, near Steers’ original “Old Dock” (now long filled and covered with buildings). He built Albert Dock to take the biggest ships of its era, as big as Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s famous 1,000-ton iron steamship Great Britain. Hartley created a 7.75-acre square pool, surrounded on all sides by massive granite wharfs (a Hartley design trademark).

Two 15-foot locks brought oceangoing ships into a midtide basin, then into the main basin at high tide level. Along his wharfs he placed a continuous series of five-story, high-ceiling brick warehouses, all with full basements completely sealed against the water. He designed the ground floor to have a large offset for offloading cargo, but with the upper floors overhanging to the edge of the pool for easy hoisting. The four upper stories were carried over the recessed ground floor on massive iron Doric columns. Altogether, Hartley provided 1.25 million square feet of storage. Hartley placed little by the way of ornament on this grand project; it was massive, elegantly proportioned and beautiful.

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img5" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img6" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img7" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img8" align="aligncenter" width="874"]

Jim Hargan

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img9" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

Albert Dock was a lot more than a dock and a warehouse; it was a complete, self-contained seaport. High walls secured it from casual pilferage, while a full-time staff and hydraulic hoists (the first in Britain) replaced casual pickup labor. Cargo moved quickly and efficiently from holds straight into the surrounding bonded warehouses. The piermaster and other officials lived on site, and a large dock office provided all the support functions needed. Not only was it safe from thieves and tax scofflaws, it also was safe from fire. Hartley did a series of tests, building small structures and trying to burn them with barrels of pitch, before settling on floors made of shallow brick barrel arches placed on cast iron pillars, and a roof of his own invention, made up of tensioned iron plate.

Within 40 years, however, Albert Dock was out of date, its locks too small due to a change that, ironically, Hartley had started at Albert Dock. In the early 20th century, machine handling of cargo took over completely, eliminating the sacks and barrels for which the dock was designed. Albert Dock closed to shipping in 1920, and lost 15 percent of its warehouses to German bombing in 1944. The Liverpool Harbor Board didn’t bother to rebuild the damaged parts. It continued to rent out the undamaged portion until 1972, and then abandoned it.

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img10" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

Jim Hargan

For 10 years, Albert Dock remained derelict. A hodge-podge of local authorities bickered over who was going to tear it down and replace it, but Hartley’s resilient construction protected it from government boards as it had from German bombs. In 1981 the Thatcher government unilaterally settled all local controversies by creating Merseyside Development Corporation, under the direct control of cabinet minister Michael Heseltine, dedicated to restoring the Liverpool region to its old glory. Heseltine’s MDC quickly decided to make Albert Dock the centerpiece of its plan. By 1984 it had restored the tidal locks and made the pool shipshape, repaired the first of the warehouse blocks and restored the neoclassical red sandstone dock traffic office. All work was complete by 2002.

[caption id="LiverpoolsAlbertDock_img11" align="alignleft" width="534"]

PETE JENKINS/ALAMY

Today’s Albert Dock has become the centerpiece of Liverpool tourism. The Tate Liverpool modern art gallery occupies five stories in one warehouse block, while Liverpool’s Merseyside Maritime Museum occupies an even larger space in the warehouse directly opposite. The ground floor walk is lined by shops, restaurants and nightclubs. At the opposite end, The Beatles Story museum draws crowds daily. Beside it, the Premier Lodge Hotel gives its guests full-sized modern rooms within the charmingly converted warehouse, along with a pub and restaurant. The transformed dock has so revitalized Liverpool that the European Union has named the resurgent port city its European Capital of Culture for 2008. Once again, Albert Dock has worked its magic.

Comments