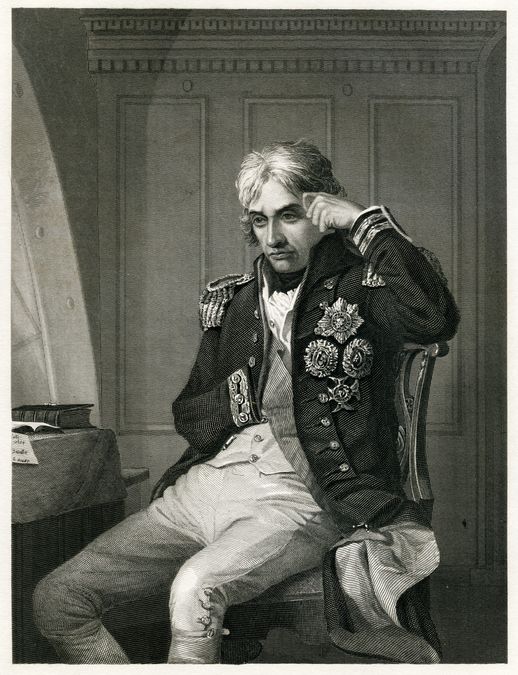

Horatio Nelson.Image:Getty Images

On the 9th of Jan, 1806, Lord Nelson, naval commander, and hero of the Battle of Trafalgar was buried at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

Nelson's Column and Trafalgar Square are two of Britain’s most iconic landmarks. When remembering Lord Nelson, it is appropriate to acknowledge the crucial role he played in shaping Britain into what it is today.

In portraiture, caricature and fancy dress, Nelson is instantly recognizable as the semi-blinded, one-armed diminutive naval officer whose army destroyed French and Spanish fleets, and who was involved in an interesting ménage à trois with Lady Emma Hamilton. Incidentally, he never wore an eye patch and it is questionable that he saved Britain from invasion by Napoleon. He did, however, say, “Kiss me, Hardy,” and Captain Thomas Hardy did kiss him, twice. Above all, however, Nelson was an outstanding naval tactician.

Read more

We know little of Nelson’s childhood

Horatio Nelson was born on September 29, 1758, in Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk, where his father, Edmund Nelson, was rector. His mother, Catherine Suckling, who died when Horatio was 9, was related to Robert Walpole, Britain’s first prime minister.

This early biographical brevity lacks insight into his character’s formation. Nelson’s sense of devotion to God, country and duty possibly originated from his father’s sermons, which probably had a contemporary nationalistic tone. Nelson is revered as a paragon of manly virtues: boldness, ruthlessness, feckless risk taking, impudence and audacity. All those traits appear to have been nascent in Nelson when he joined the navy at the age of 12 in 1771. His naval career was simply a theater for their expression and refinement as he searched for glory.

Nelson, on his own initiative, requested his father’s assistance to enlist into the Royal Navy. This was achieved through two uncles, Maurice and William Suckling, who had risen to influential levels in the naval hierarchy. Initially, Captain Maurice Suckling ensured young Nelson’s assignments were appropriate to obtaining seafaring skills and promotions. There is a whiff of nepotism in Nelson’s early promotions as he learned the ropes of sailing, but the 18th-century navy worked more on patronage than merit.

4

4

Lord Nelson

Lord Nelson

For 21 years Nelson was based in the North American or West Indian stations

This was a frustrating period for him as there were few opportunities for action; what little action there was left him wanting more. Nonetheless it was an instructive period.

Through the auspices of Admirals Lord Hood and Sir John Jervis, Nelson learned that a well-disciplined ship was not a vessel ruled by the cat-o’-nine-tails but one where every man knew, and flawlessly executed, his duty. Nelson also came to understand that Britain’s sovereignty was dependent upon sustaining economic superiority over France and Spain; any affront to this was unpatriotic and had to be stopped.

Nelson returned to London in 1792 with clear ideas of naval leadership and a wife and stepson, but he lamented not having had the opportunity to participate in a major naval battle. He told friends in letters that it was his ambition to lead a line of battleships into glorious action and die a hero.

The danger Nelson craved was soon to come. In 1793 the uneasy peace with France ended. Nelson was placed in command of HMS Agamemnon and sent to serve under Admiral Jervis in the Mediterranean. Over the next five years he repeatedly distinguished himself with displays of bravery, coolness and fine judgment. In this period he was blinded in the right eye at Corsica in the Battle of Calvi. Also in this time, during an overzealous assault on Santa Cruz, Canary Islands, he received the wound that resulted in his arm being amputated.

READ: The abolition of the British slave trade

Nelson earns his stripes

The battle-scarred Nelson came fully to the attention of the nation after the Battle of Cape St. Vincent. The combined desire to cause mayhem in the French fleet and his innate craving for glory impelled Nelson to courageously board and capture two enemy ships. Nelson enjoyed public admiration for his combative achievements, admiration that he flamed with letters to influential newspapers. The bestowal of a pension, knighthood and promotion to rear admiral further massaged his insatiable ego.

More glory shortly followed. Nelson was ordered to hunt and destroy the French Mediterranean fleet. Napoleon’s strategy was to invade Egypt and cut Britain’s vital commercial route to India, so an economically weakened Britain would not threaten his European ambitions. With a fleet of 14 ships, Nelson located the French fleet at anchor in Aboukir Bay, near Alexandria, on August 1, 1798. The Battle of the Nile was about to commence.

Though it was late in the day, Nelson, seeking glory and a decisive victory, attacked. His strategy was audacious and, as he was victorious, is considered brilliant. Traditionally, naval battles were conducted with opposing fleets forming parallel lines and pummeling each other until, through attrition, one side was clearly defeated.

Pierre Charles de Villeneuve, the French rear admiral, anchored his ships against shallow water believing the British ships would be unable to sail there, forcing them to come alongside his powerfully armed and prepared deepwater flank. His confidence was such that he did not prepare his shallow-water flank’s defenses. Nelson, a ruthless predator, crossed the enemy’s poorly armed prows and sterns, into the shallow water and bombarded the French ships’ unprotected flank. It worked to devastating effect: Nelson annihilated the French fleet.

News of Nelson’s victory was rapturously received in London. The one-eyed, one-armed rear admiral became the idol of England. Nelson thoroughly enjoyed the adulation, the conferral of a barony and promotion to vice admiral. Unfortunately for Nelson, his Nile victory was so complete that it resulted in a frustrating few years of naval inactivity.

Lord Nelson

By 1803 Napoleon was redrawing the European political chessboard and once more challenging Britain’s sovereignty

Nelson, now 45, was recalled from semi-retirement to take command of the British Mediterranean fleet on board HMS Victory, which, in an ironic subtext of history, had been commissioned the year of his birth.

In 1805, Spain was allied with France; Napoleon was amassing thousands of troops in the French channel ports awaiting the arrival of the combined Franco-Spanish fleet to form an invasion flotilla. A successful invasion depended upon drawing off the protective British fleet. As a ruse, the Franco-Spanish fleet headed for the Caribbean, pursued by Nelson. The enemy fleet, ahead of Nelson, was prevented from reaching the channel ports and diverted to Cadiz, Spain. Viscount Nelson was again the hero of the hour because he had prevented the French from seizing Britain’s Caribbean possessions. Despite Napoleon abandoning his invasion of Britain, his fleet was still a substantial menace.

The Franco-Spanish fleet left Cadiz on October 19, 1805. By 1 a.m. on the 20th Nelson knew its precise location, but delayed engagement because he wanted the ships to be farther from their bolt-hole. During the night, Nelson’s captains reflected on his last memorandum, known as the Nelson Touch, which finished, “In case signals can neither be seen or perfectly understood, no captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy.' This was tactical excellence. All his captains, appointed by him on merit and in his confidence, knew the battle plan, but Admiral Nelson was allowing for unforeseen contingencies.

The viscount’s plan was simple and bold. The British fleet would divide into two lines and cut the Franco-Spanish fleet in three; the van would be isolated from the action and Nelson’s 27 ships would attack the mid and rear lines—brilliant. Except there would be a period, perhaps 20 minutes, when the British ships would be unable to return fire. Nelson, confident as ever in his plan, courageously led the attack. In the final approach on the enemy fleet, Lord Nelson made the signal that is now synonymous with his name; ''England expects that every man will do his duty.”

Nelson was about to do just that. At approximately 12:35, HMS Victory came under fire and was unable to return fire until 1. At 1:15 Nelson was shot by a sniper from the rigging of Redoubtable. He remarked to Hardy, Victory’s captain, ''They have done for me at last, my backbone is shot through.”

Horatio Nelson died with the closing words, “Thank God I have done my duty,” having achieved his primary ambition: a glorious death in battle.

Nelson’s death in victory compounded his heroic status. His elevation to supreme hero, almost a deity, was confirmed as his state funeral on January 9, 1806, was solemnly witnessed by tens of thousands. Lord Nelson’s death was immediately commemorated in monument, in street and building name and in contemporary song, art and poetry. Nelson would have approved of Lord Byron’s accolade describing him as “Britannia’s God of War.”

Nelson's column

Nelson’s legacy goes beyond art and place names

His actions at Trafalgar influenced global military and political affairs for more than a century. Nelson’s victory established the British navy as the most powerful in the world, such that Britannia ruled the waves unchallenged for more than 100 years.

Victory at Trafalgar also gave the nation of shopkeepers the confidence and arrogance to believe that their imperial ambitions were correct. It was the foundation and impulse for Britain’s colonial and industrial growth into a world-dominating power. This is epitomized in “Rule Britannia,” a powerfully rendered song reflecting Britain’s self-confidence, a song that Britons still passionately sing.

While remembering Nelson’s death, visitors to Trafalgar Square may look up to Horatio Nelson in a renewed light. Soaring above them is a little man whose innate predatory instincts for victory and glory shaped much of their heritage; without his victories at Cape St. Vincent, the Nile, Copenhagen and Trafalgar, today’s geopolitical map would be very different.

READ: 6 of our favorite British couples

* Originally published in June 2018.

Comments